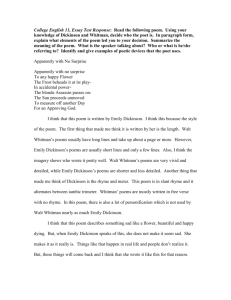

Life of the Woods A Study of Emily Dickinson by Donald Craig Love

advertisement