Commercial super trust or virtual organisation?

advertisement

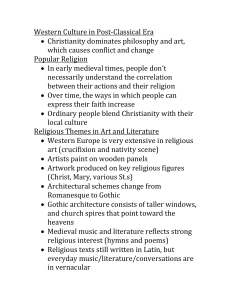

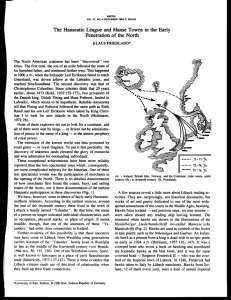

Commercial super trust or virtual organisation? An institutional economics interpretation of the late medieval Hanse* by Ulf Christian Ewert** and Stephan Selzer++ Abstract: In this paper the Hanseatic trading system is analysed using concepts of management science and institutional economics. The Hanse was neither a state of cities nor a commercial super trust. The concept of network or virtual organisation is a more realistic approach and explains, why Hanseatic merchants, by commitment to reciprocal trade, cooperated mainly without formal contracts. In this particular setting, transaction, information and organisation costs were low. A fair conduct was enforced by trust and reputation, and merchants could minimise agency risks. The trade network was embedded in a broader institutional arrangement and thus was perfectly adapted to the commercial environment in the Baltic. The Hanse’s later inability to expand and its decreasing competitiveness were path-dependent, because they were also triggered by certain deficits of this network organisation. Focus of the paper The Hanse probably is one of the most dazzling phenomena in the economic history of the Middle Ages. The mere economic facts are quite impressive. From thirteenth to early sixteenth centuries Hanseatics, who mostly were self-employed merchants, were able to deliver all sorts of goods to the consumers in the ever growing cities everywhere in the Baltic. Merchants defended together and with great success the Hanseatic trade privileges they had obtained in London, Bruges, Bergen and Novgorod, the places, where they founded the Kontore of the Hanse. And despite they neither had formed large firms nor had adopted state-of-the-art trading techniques, merchants could maintain their monopoly of trade on Baltic markets until the turn of the fifteenth century. The Hanse’s outward appearance is nevertheless shaped until today by the Hanseatic League, the alliance of towns that had emerged by the middle of the fourteenth century. The Hanseatic League appears as a kind of omnipotent political superstructure of the Hanse, which in fact it never was. Yet, given this biased interpretation1, the Hanse seems to have been a state of cities and a huge mercantile empire at the same time, a sort of late medieval North European super trust. * Working paper prepared for the Eighth European Historical Economics Society Conference, to be held at the Graduate Institute Geneva, Switzerland, September 4–5, 2009. ** Philosophische Fakultät I, Institut für Geschichte, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Hoher Weg 4, D-06099 Halle (Saale), Germany, e-mail: ulf-christian.ewert@geschichte.uni-halle.de. ++ Fakultät für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften, Professur für Mittelalterliche Geschichte, Helmut-Schmidt-Universität. Universität der Bundeswehr, Holstenhofweg 85, D-22043 Hamburg, Germany, e-mail: stephan.selzer@hsu-hh.de. 1 Cf. for a description of the changing interpretations of the Hanse in nineteenth and twentieth centuries historiography SELZER/EWERT 2005, pp. 8–18. See on the Hanse in general DOLLINGER 1989; HAMMEL-KIESOW 2000. 1 Unfortunately, not much of this quite fascinating tale is true. And it is especially the economic chapter of the story, which raises questions instead of providing answers. Historical research on the Hanse is in a sense governed by a threefold paradox: On the one hand side, most of the newer publications are dealing with social history and the cultural history approach, although the Hanse first of all is certainly an economic historical issue. On the other hand, if the economic character of the Hanse is the subject of analysis, seldom this is done from an economist’s perpective and by using economic theory.2 Lastly, the different elements of the Hanse such as the Kontore, the Hanse diets or the quite unique reciprocal trade pattern of Hanseatic merchants are very often studied as isolated cases. Hardly any attempt is made to put all these different pieces together. GREIF, MILGROM and WEINGAST3, for example, gave of course a path-braking and theoretically sound explanation of the Hanseatic guild formation at the Kontore, but the Hanse cannot be reduced to these commercial outlets alone. Thus, it is herein attempted an economic analysis of the Hanseatic trading system, an analysis that is based on the fairly safe grounds of economic theory and in particular shall reveal the interplay of different Hanseatic institutions. Within the sections of the paper the following questions will be discussed: Which theoretical concept could be suitable for a description of the organisation of the Hanse? What kind of incentives were provided by this organisation for merchants? How could this structure work successfully? What specific structural deficits might have caused the later decline of the Hanse? The theoretical concept: network approach and virtual organisation First of all, a theoretical concept able to describe the Hanseatic trading system and to explain its structure in economic terms is presented. Networks and virtual organisations Similarly to the terms »system« and »social capital« the term »network« is very popular indeed and seems to be well-known. As in the case of the two other terms also »network« is widely used in social sciences and history, and a broad range of meanings is attributed to the theoretical concept underlying the term, too. For the 2 There are of course exceptions to this rule, namely SCHONEWILLE 1997; 1998; STREB 2004; JENKS 2005; LINK/KAPFENBURGER 2005. 3 Cf. GREIF/MILGROM/WEINGAST 1994. 2 purpose of being as precise as possible, »network« herein is used with respect to its meaning in management science, there describing a specific form of organisation.4 A network organisation is thus defined as a loose cooperation of legally and economically independent entities. Through »networking« a »new« structure evolves which constitutes the framework for potential cooperations between the members of such an interorganisational network. In theory, this »new« structure – the interorganisational network – neither possesses hierarchical levels nor is controlled from headquarters, because cooperations between network members are thought of as being voluntary and flexible couplings.5 Network organisations therefore are characterised by a low degree of formalism and a lateral flow of information. Since coordination within such an organisational pattern in principle cannot be archieved by either hierarchical means of coordination or third-party enforcements, cooperation has to be guaranteed by mutual trust and reputation.6 As an aside of having only loose couplings network members can be involved in both cooperation and competition at the same time. This so-called feature of »cooptition«, underlining the flexibility of existing couplings, is believed to increase the network’s overall performance through internal competition.7 If a network organisation in addition has the characteristic of being only virtually existent, it is called a virtual organisation. With this specific pattern the lack of a formally well-defined hierarchical-bureaucratic structure can be hidden to the environment. From an outside perspective such a virtual organisation only appears to be structured like a very complex and huge trust. In fact, features like formalism and complexity are only imitated with this structure. Nevertheless, the performance of a virtual organisation and the services it is able to deliver are equivalent to those provided by a highly formalised hierarchical-bureaucratic organisation. Information processing and the structure of the flow of information are playing key roles for virtual organisations in being able to perform like that. The lateral flow of information requires devices that are capable to process vast amounts of information very quickly in order to substitute for the hierarchy that is missing. Thus, the model of virtual organisation is a special case of network organisation.8 4 Cf. POWELL 1990; NOHRIA 1992; GALASKIEWICZ 1996; THOMPSON 2003. Cf. POWELL 1990; ILLINITCH et al. 1996; OSBORN/HAGEDOORN 1997; WINDELER 2001. 6 Cf. POWELL 1990, GALASKIEWICZ 1996 and OSBORN/HAGEDOORN 1997. 7 »Cooptition« is a coinage out of »cooperation« and »competition« that came in use in the literature on network organisations. Cf. BECK 1998. 8 See for an introduction to this concept SCHOLZ 1996 and KRAUT et al. 1999. 5 3 The Hanse’s network trade and its virtual character The theoretical concept of network business and virtual organisation now can be applied to the commercial relationships that existed between Hanseatic merchants in the late Middle Ages. A hierarchical-bureaucratic corporate organisation, which already was a common pattern used by Italian merchant bankers and trading businesses from Upper Germany9, can rarely be found along the coasts of the Baltic sea. In contrast to handle their trading operations by employing agents who had to be instructed on a regular basis, the organisational mode of the hanseatic businesses typically consisted of mutual transactions between two partners residing at distant locations, each partner selling the other partner’s goods. These cooperations neither needed formal contracting nor have they been exclusive, and the selling merchant was usually not payed for taking the commercial risk of a sale. The organisational pattern that had evolved through the trading activities of hanseatic merchants is typical for a network organisation.10 Small-scale businesses of self-employed merchants with little financial power each formed trading networks by mutually cooperating via reciprocal trade. Not only was the bilateral exchange between members of these networks based on an informal consensus, also headquarters capable of coordinating and controlling the activities of the numerous network participants were virtually not existent. Moreover, as network members were allowed to trade with many partners all over the Baltics, the network structure in principle was characterised by both cooperation of its members and a timewise and casewise competition between them. Thus, Hanseatic trade networks were medium-term or long-term cooperations on the basis of informal and only implicitly defined contracts between legally independent merchants. Very often the commercial partners were related to each other or were attached to each other through friendship relations.11 They appear to have been a socalled »small world«, since they, despite having only a weak overall density, allowed each member to get in contact with any other participant via only a few mediating persons.12 Moreover, the particular structure of trade inside the Hanse that originated from the multiple trading relationships of single merchants to a considerable degree also 9 10 11 12 Cf. BAUER 1923; VON STROMER 1968; RIEBARTSCH 1987; HILDEBRANDT 1996; 1997 Cf. SELZER/EWERT 2001; 2005; 2009; EWERT/SELZER 2007; EWERT/SELZER 2009c. Cf. SPRANDEL 1984; STARK 1993. Cf. WATTS 1999. 4 shows the characteristics of a virtual organisation. This »virtualisation« of structure is obvious in at least two respects: Firstly, although all sorts of goods by chains of commercial transactions involving many merchants were carried to every market in the catchment area of the Hanse13 and although a high and homogeneous product quality was guaranteed by a standardisation of weights and measures14, for single merchants as well as for customers these efforts certainly did not appear as if they could have been archieved without implementing complex formal structures. Secondly, the Hanseatic League15 as an alliance of cities that had emerged in the middle of the fourteenth century still shapes the Hanse’s present-day outward appearance. Although the Hanseatic League never really had a headquarters’ function for hanseatic trade, contemporary foreign merchants recognised their hanseatic competitors as belonging to a group sharing privileges they themselves would have liked to share. And also for many generations of historians the Hanse had the image of a huge trading trust or a mercantile empire, a false interpretation to which even nowadays observers still are sticking to.16 Nevertheless, believing this, even if it is not adequate, very much points to the feature of virtuality, and a quite evident conclusion would be that the Hansa very successfully mislead non-hanseatic merchants as well as historians in more pretending to be a formally well-defined trust than really being it. The incentive structure: non-hierarchical coordination, cost efficieny and the coverage of agency risks Once the Hanseatic trading system can be described in terms of a consistent concept, in a second step we shall look at the design of institutions within this system and the incentives these institutions provided for merchants to cooperate. Following NORTH »institutions« are herein understood as the humanly shaped rules governing and social exchange between Hanseatics.17 The problem of free-riding and potential agency risks Numerically the by far most important exchange pattern was the above mentioned reciprocal trade, a cooperation of two merchants, each of them operating at distant 13 Cf. HAMMEL-KIESOW 2000. Cf. JENKS 2005. 15 Cf. WERNICKE 1983; HENN 1984; PITZ 2001. 16 See for instance still recently PICHIERRI 2000. SCHELLERS 2003 in contrast analyses the Hanseatic League with respect to its characteristic as an alliance of cities with primarily political purposes. 17 Cf. NORTH 1991, p. 97. 14 5 locations and selling the other partners’ goods and products. In these informal partnerships, which usually were handled without written contracts and which could last for years or even for decades, profits of a trade were pocketed by the sender only whereas the risk remained only with the partner who operated the sale.18 In networks consisting of numerous such bilateral business partnerships usually the problems of free-riding and cheating arise19, especially if a considerably large number of participants is involved.20 Without having written contracts, at first glance it looks like as it must have been very easy to participate in a commercial network of Hanseatic merchants, to take personal benefits from it, by selling for instance another merchant’s goods and pocketing the profit, but not to contribute substantially to the network exchange by refusing to sent own goods to this merchant in order to recompense him. Thus, trading activities had to be coordinated somehow and network members needed some kind of enhancement in order to behave fair. This was provided by reputation, trust and culture, all these being means of coordination which could compensate for a missing hierarchy.21 However, through their commitment to this kind of reciprocal trade the merchants could also keep transaction, information and organisation costs low. Moreover, they had a powerful tool at hand in order to assure themselves against the classic problems that typically evolve in principal-agency relationships. These problems are known in the literature as the contractual risks of adverse selection, moral hazard and hold-up.22 Coordination by reputation, trust and culture Reputation played a fundamental role in the enforcement of a fair conduct of the members of Hanseatic trade networks. This can easily be shown by using a gametheoretical approach. Following GREIF’S idea, a trade relationship is modelled as a one-sided sequential prisoner’s dilemma.23 Within this framework the form of recip- 18 Cf. MICKWITZ 1937; 1938; SPRANDEL 1984; STARK 1993; CORDES 1998; 2000. Besides this, Hanseatic merchants used for particular trade operations also a sort of commission business, the socalled sendeve. In this well defined contractual sheme the commission agent sold the goods he had received from another merchant by order and for account of the partner who had formally instructed the sale and had sent the goods to the commission agent, with profits and risk remaining with the sender. Cf. CORDES 1998; 1999. 19 Cf. TESFATSION 1997. 20 Cf. DIEKMANN 1992. 21 See in general POWELL 1990; GALASKIEWICZ 1996; STABER 2000. 22 Cf. RIPPERGER 1998, pp. 63–67; WOLF/GRAßMANN 2004. 23 Cf. GREIF 2000, pp. 254–256. Here, each of the two partners involved in mutual exchange would be at the same time a »principal«, who is sending goods to the partner, as well as an »agent«, who is receiving goods and selling them for the sender. While playing these roles merchants are as- 6 rocal trade, which was predominant among Hanseatic merchants, does not create any incentive for the participants to act fair. In a one-shot situation, for the partner who was selling the other’s goods the gain p by cheating in any case would have been bigger than a zero return from fair behaviour (see Figure 1a). Figure 1: Game theoretical analysis of Hanseatic reciprocal trade (a) ts no en gg din d oo oB st AB [0, 0] od go ng i l l se not compensating A sending goods to B merchant A (“principal”) o sf rA A B [p, 0] A B [-cA, p] merchant B (“agent”) (b) ts no en g din oB st od go AB [0, 0] lin sel sending goods to B merchant A (“principal”) o gg s od fo rA not compensating A A B [p, r] A B [-cA, p-r] merchant B (“agent”) Game-theoretical model of reciprocal trade: p = profit of sale; cA = costs of sending goods to B; r = reputation (r < p). (a) One-shot situation without incentives for B to act fair; (b) One-shot situation with accounting for B’s gains of reputation in the event of acting in A’s interest. Source: authors’ own calculations and drawings In principle, this defect can be removed by assuming that a selling merchant (B) would gain reputation r for each transaction where he acts in the proper interest of his partner (A), the owner of the goods. Likewise, B would lose his reputation if he is cheating. However, as a quite plausible assumption would be letting r be lower than p, the intended incentive for merchant B to act fair and handle A’s goods with care, would only take effect in a more realistic scenario, where trading activities could be repeated infinitely (see Figure 1b).24 Since merchant B will only be chosen again as a commercial partner by merchant B or any other merchant in the network in case he is sumed to have a choice: as »principal« they can decide upon sending their goods; as »agent« they can decide whether to cooperate or not. See on this model in more detail EWERT/SELZER 2009C. On gametheoretical approaches to the history of trade see also GREIF 2004. 24 Assuming infinity of repetitions is plausible insofar as both partners in reality were not knowing when exactly their exchange relationship would come to an end. 7 trustworthy, the infinite sum of reputation values ( r) will exceed the one-time gain Σ of (p-r).25 Thus in the long-run reputation of merchants was a strong means to enforce a reciprocal fair comportement. Being a reliable trader of high standing was essential to all members of a network. Not to lose this reputation was a strong incentive to keep to the network rules. Similar to the findings of GREIF for the Maghribi Traders26, the Hanseatic reputation mechanism was a multilateral one. Losing reputation due to cheating or betrayal thus not only undermined a particular bilateral relationship, it automatically meant also losing access to the whole network and thus losing possible future partnerships. Because of this multilateral reputation mechanism27 the Hanseatic network trade was in a sense a self-enforcing institution. Hanseatic societies and sociability enabling institutions the Zirkel-Gesellschaft 28 of Lübeck or the Artus courts 29 greatly contributed to this reputation mechanism insofar as it was in the societies’ functions and informal meetings in which participants of a network were regularly provided with information regarding the reputation of other network members. Starting from there information on the reputation of other network members could be distributed across the whole network.30 In contrast to exchange-related information that was needed to be transmitted quickly in order to control particular trade operations, for information on reputation it was only necessary to be announced anyhow for preventing fraud among merchants. There is plenty of evidence, for example, that the names of those merchants, who were not longer accepted to share the privileges of the Hanseatic League in Bruges, were published in the Artus courts.31 Joint membership of merchant and councilors in societies or fraternities as well as closeness within a town obviously helped the merchants to make city councilors an instrument in advocating commercial interests. Thus, design and functionalism of trade networks are proving quite well, that commercial purposes and social practises of Hanseatic merchants overlapped to a fairly great extent.32 25 See for an application of a repeated sequentiel game to the conflict between the council of Nuremberg and the cities’ guilds in the late Middle Ages and early modern times LEHMANN 2004. 26 Cf. Greif 1992; 1993. 27 See on the impact of reputation-based institutions in medieval trade GREIF 1992, p130; 1993, pp. 531–535; GREIF 2000, pp. 260–272; GREIF/MILGROM/WEINGAST 1994, STREB 2004; EWERT/ SELZER 2007; and quite recently GONZÁLES DE LARA 2008. 28 Cf. DÜNNEBEIL 1996. 29 Cf. SELZER 1996. 30 Cf. SELZER 2003, pp. 84 and 96f. 31 Cf. SELZER 1996, p. 105. 32 Cf. EWERT/SELZER 2009b. 8 In this particular setting trust was of enormous importance in helping to coordinate network activities.33 The organisational pattern of networks commonly is called a »total-trust« organisation, stressing the tremendous contrast to the model of a »zero-trust« bureaucratic-hierarchical organisation, where control is archieved via hierarchies and instructions.34 Trust usually increased with the endurance of a mutual relationship. By the reciprocity of actions – sending goods to a partner if goods from him were obtained, selling the goods received if he also sells the goods sended to him – the problem of free-riding in a situation almost without hierarchical means of coordination could be solved. Since trust had to be built up over a considerably long period of time, a step by step approach had to be taken by the merchants in order to substitute trust during the phase when the mutual relationships just had started and also in case they were trading with occasional partners. In game theory this phenomenon generally is described as Tit-for-Tat strategy.35 The growing volume of the transactions between Hildebrandt Veckinchusen and Gerwin Marschede may be cited as an example for the presence of this mechanism within Hanseatic commercial networks.36 Very often, it also was tried to tighten personal ties by mutual gift-giving.37 Finally, shared common values also facilitated mutual cooperation indeed. Coordination by culture38 was essential to a smooth organisation of Hanseatic business networks. This means, that in principle all members of a trading network agreed upon common values and norms and acted in accordance with these values and norms. This mechanism of coordination was especially of importance within the core partnerships of individual merchants, which to a large extent were trading partnerships with family members and close friends. It should be noted, that also a kind of latent harmonisation emerged, which was more or less a by-product of the Hanseatic merchants’ commercial activities all over the Baltic. This nevertheless turned out to be of great value for their economic transactions. With shared values and common norms it was possible to create a more homogeneous mercantile setting indeed. However, the homogenisation of cultural beliefs certainly was not a clear strategy that had been deliberately implemented, but as Hanseatic merchants were present all 33 Cf. KRAUT et al. 1999, p. 726; CHILD 2001; GREY/GARSTEN 2001; TOMKINS 2001. Cf. REED 2001. 35 Cf. AXELROD 1984; HÖFFE 1988; RAPOPORT 1992; HÅKANSSON/SHARMA 1996, pp. 116–117. 36 Cf. STARK 1985. 37 See for some examples from Riga, Königsberg, Oslo and Rostock STEIN 1898, pp. 89–91, Nr. 10, pp. 93–97, Nr. 13, and p. 114, Nr. 21; STARK l984, p. 141; THIERFELDER 1958, p. 209. 38 Cf. for instance JONES 1983. 34 9 across the Baltics, it was a rather unintended but nonetheless natural process that over time cultural beliefs and practices became more and more equal to each other. Shared common values were probably very obvious inside the merchants’ families and therefore were spread out across the areas of Hanseatic trade with those family members settling at market places that were distant to their family’s home town. Cost-efficieny and the coverage of agency risks The networking strategy was of most valuable economic benefit to Hanseatic merchants in terms of the high degree of flexibility they could gain from it while at the same time having chosen an organisational pattern which caused only moderate costs. Individual-level gains of networking are derived from the transaction costs approach.39 Shared common values, that were probably very obvious inside the merchants’ families but certainly materialised in festivities and marriage patterns and in having a good command of the Lower German language40, facilitated mutual cooperation indeed. Therefore transaction costs remained low. By reciprocal exchange of goods mutual trust between partners could be built over the course of time allowing the merchants to leave the collection and processing of information relevant to sales’ operations on foreign markets with their respective partner. Thus, also information costs were negligible. A fair comportment of all network members was enforced in the Hanseatic case through a multilateral reputation mechanism. By relying on such an mechanism of enforcement the problems of free-riding and controlling agents were solved such that reciprocal trade without entering into formal contracts and without assuming speedy communication lines was a viable and self-enforcing mode of commercial exchange inside the Hanse. This in turn allowed to keep also organisation costs within the networks at a fairly low level.41 As the reputation of trading partners was well-known to everyone in the network, in this framework the risk of an adverse selection, that is, choosing a wrong trading partner, was very unlikely. Through the threat of losing their reputation partners involved in a commercial exchange relationship were encouraged to act primarily in the other partner’s interest, this comportment also minimising the risk of moral hazard. The same threat of losing reputation prevented the merchants also from taking advantage of a possible »hold-up-position« they in principal would have gained due 39 40 41 Cf. COASE 1937; 1984; WILLIAMSON 1979. Cf. DE BOER et al. 2001. Cf. SELZER/EWERT 2001; 2005; EWERT/SELZER 2009c. 10 to the investment their trading partners had made by sending goods to them. Because of the reciprocal design of commercial exchanges each party held the other’s goods and could use these items at any point in time as a security asset in order to face a possible hold-up by the partner.42 Determinants of succes: adaptation to the commercial environment and a balanced design of institutional arrangments How could the Hanseatic system of trade work so successfully for such a long period of time? Was it only the network driven by reputation, trust and the cultural correspondence of network members that enabled Hanseatic merchants to monopolise trade in the Baltic during the late Middle Ages? Presumably not, although the network pattern of trade certainly was very important for the commercial success of the Hanse. Thus, the reason for the Hanseatic network organisation to work efficiently was not only its organisational design, but also the embeddedness of this structure in a broader institutional arrangement favouring this design.43 We therefore examine in a third step strategies that were able to enhance furthermore the commercial exchange of Hanseatics within trade networks. A quite clear pattern of reactions can be seen inasmuch as commercial risks were tried to be minimised by both individual non-formal rules and corporate formal institutions. Coping with commercial heterogeneity Hanseatic merchants indeed were confronted with a great deal of diversity concerning their trade during the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, in particular because this commerce covered a whole range from highly integrated and very efficient markets with well developed juridical and financial institutions in the West to poorly developed and very inefficient markets in the Northeast. Heterogeneity thus seems to have been an important determinant of Hanseatic trade. Interestingly enough, it was this economic and cultural divergence within North Europe which had been one of the key factors that initially had allowed Hanseatic merchants to gain significant commercial advantages over their former competitors. Because they were able to link these separate regions commercially, Hanseatic merchants could nearly monopolise trade within this area. The network structure thus perfectly fit into this commercial context, which in addition to its diversity was characterised by its vast spatial extent, 42 Cf. SELZER/EWERT 2001; 2005; EWERT/SELZER 2009c. 11 a rather slow transmission of information and a lack of powerful financial and legal institutions. Maintaining the rather simple form of reciprocal trade and informal cooperation between partners at distant locations was an efficacious and efficient solution to the problem of being confronted with diversity and risk. It allowed those merchants participating in the internal Hanseatic trade to operate in a rather safe and cost-efficient manner. At the same time, this business style was flexible enough to be suited to either a very sophisticated level of market development, as in the case of Bruges market with its practice of complicated cashless transactions, or to a rather poorly developed market, as in the case of Novgorod where barter trade still was predominant. A quite instructive example for the coexistence of different business styles are the activities of Hildebrand Veckinchusen who at the beginning of the fifteenth century was located in Bruges and traded from there on the basis of reciprocal relationships intensively with his brothers, his cousins, his father-in-law, his nephews and some of his friends in Lübeck, Danzig, Riga, Reval and Dorpat.44 Besides this, he was also part of a quite formal society by which he operated his trade with Cologne.45 Given the fact, that the strategy of forming trade networks and therefore staying flexible was of an enormous benefit to merchants, this rather simple and seemingly old-fashioned looking business style can be considered as a key element for them to balance the effects of commercial diversity. By this Hanseatic merchants could very well bridge, and to a certain degree even close, the gap between the various mercantile environments that existed inside the Hanse.46 Hedging against the risks of transportation Maritime trade was virtually the only viable way to bridge the huge distances in the Baltic and in the North Sea, and thus merchants had to find solutions to the problem of dealing with the specific risk related to this trade. Although in the Middle Ages seaborne trade was not that much faster than overland transportation, it usually was fairly unpredictable due to changing weather conditions and the threat of piracy, and therefore a lot of risk was involved in it. 43 44 45 46 See on the concept of network and institutional embeddedness ROOKS et al. 2000. Cf. IRSIGLER 1985; STARK 1993; CORDES 1998; GREVE 2002. Cf. SCHWEICHEL 2001. Cf. EWERT/SELZER 2009a. 12 For their trade in the Mediterranean Venetian and Genoese merchants relatively early had developed contractual forms like the commenda or the collegantia which clearly regulated the responsibilities for such an enterprise and the costs of risk and which also made it for merchants more likely to find risk capital for potential commercial enterprises.47 A quite similar problem was solved by Hanseatic merchants in a more informal and non-contractual manner. In the old-style caravan or convoy trade goods had been protected against risky events to some extent by the organisational pattern of the caravan itself. Seeking for this sort of protection presumably was the main reason why in the past all over the world and across all civilizations merchants in early trade had chosen such a caravan trade organisation. Once caravan and convoy trade in many Hanseatic regions had been replaced by an office-based form of trade, Hanseatic merchants, in contrast to their Italian contemporaries, had seemingly neither developed a formal sea insurance nor adopted the widespread use of formal contracts regulating the distribution of liability and risk between trading partners.48 Instead, they attempted to hedge against the risk of transportation by using a more basic form of risk diversification. Usually, Hanseatic merchants tried to ship the commodities in a trade sample on several ships, and in the event they were also ship owners, they commonly did not concentrate their investment on one ship only.49 As these solutions were not self-enforcing in a sense that an individual merchant was not able to get accepted his property rights claim by own measures if these rights had been violated, these individual strategies of hedging against risk had to be sustained by general Hanseatic formal regulations regarding the liability for the loss and the damage of commodities while being shipped.50 Standardising and harmonising the commercial institutions Of course, Hanseatic merchants also tried to standardise and to harmonise the different mercantile environments they were operating in. Both the standardisation of weights and measures and the harmonisation of juridical regulations and cultural beliefs could help to reduce transaction costs in Hanseatic trade. 47 Cf. LOPEZ 1976. Of course, Hanseatic merchants also used a contractual type, that was called the wedderleginge or kumpanie and that very much resembled the Mediterranean commenda, by which for a specific endeavour capital could be accumulated. Both partners in such a contract added their financial resources, but only one of them operated the trade whereas profits were shared between the two of them. This sort of contract nevertheless was only of minor importance for Hanseatic trade. Cf. EBEL 1957; CORDES 1998; HAMMEL-KIESOW 2000. 49 Cf. WOLF 1986. 48 13 The Hanse and their merchants were pretty much aware that differences in infrastructure, economic and financial institutions of markets were inefficient and costly features of their trading system. By networking transaction costs of commercial exchange for merchants could be kept at a level that was low enough to make trade quite attractive to them, but a reduction of the heterogeneity stemming from distinct mercantile environments certainly would have helped to lower transaction costs even more. Apart from closing this system for non-hanseatic competitors in order to keep monopoly rents, it thus was a fairly rational strategy to standardise and to harmonise the various mercantile environments in order to reduce the degree of heterogeneity inside the Hanse and the amount of transaction costs for traders. Different attempts were made to create a more homogeneous commercial setting for merchants.51 First of all, the city laws of Magdeburg and of Lübeck had become the dominant city law in the Baltic. Although originating from many different Hanseatic towns or cities, most of the merchants of the Hanse acted therefore on the grounds of a commonly known and practised law.52 The Hanse then also standardised weights and measures for many of the commodities its merchants were dealing with.53 In the privileges of the Hanse both for Flanders and for Novgorod also measures to implement a quality control of commodities were taken. For instance, the wax bought from the Russian producers in Novgorod had to be sealed, either in Novgorod before it was bought by a Hanseatic merchant, or in the particular Hanseatic town or city where it was sold to another merchant, respectively. Any offence against this rule was regulated with a fine.54 Interestingly enough, a similar regulation for Novgorod furs has not been set. Nevertheless, the Hanse possessed already quite systematic and widely applied regulations of weights and measures and a system of quality control by which transaction costs were reduced in terms of facilitating the search for specific products and of passing them forward within the chain-like trade between Hanseatic merchants.55 A step further ahead on the pathway leading to commercial settings that were more equal to each other was to regulate also the juridical practices concerning overseas transportation and other matters of commerce. This was primarily done to reduce transportation risks, to guarantee fair exchange and to enforce commercial con50 51 52 53 54 55 Cf. JAHNKE/GRAßMANN 2003. Cf. JENKS 2005. Cf. EBEL 1957. Cf. WITTHÖFT 1976. Cf. JENKS 2005, p. 38. Cf. JENKS 2005, p. 39; LINK/KAPFENBERGER 2005. 14 tracts. Regulations in great detail can be found for those Hanseatic merchants that were operating in Flanders. These statutes encompassed various rules regarding the liability of merchants and that of their customers as well as regulations concerning the competence in the event of a law suit and also procedural questions. Very similar rules can be found in the Hanseatic privileges for Novgorod.56 Also a sophisticated sea right was developed by which responsibilities and liabilities for damages and losses due to averages were regulated.57 Providing rather standardised juridical procedures for shipping and for the commercial exchange between Hanseatic merchants and foreign producers, brokers and traders, lowered the transaction costs of exchange mainly by a reduction in the costs for contracting and for contract enforcement. In contrast to the network strategy, the institutional arrangements that resulted from standardisation and homogenisation were not self-enforcing ones. City governments, the Kontore and later on also the diet of the Hanseatic League were needed as »thirdparty-agents« to enforce these rules. Creating formal institutions Undoubtedly, Hanseatic merchants were entrepreneurs, who in seeking for profits from their trade definitely followed an economic rationale. Being also citizens of their respective home towns they had to respect, while carrying on their trade, their home town’s economic interests, trade regulations and juridical practices, at least to a certain extent.58 More importantly, contemporary foreign merchants recognised their Hanseatic competitors as belonging to a group sharing privileges they themselves would have liked to share. These economic privileges together with the backing of Hanseatic towns were the basis on which Hanseatic merchants could build their system of long-distance trade within the Baltic.59 They nevertheless needed a set of formal institutions for doing this, and they created institutions like the Kontore and later on the Hanseatic League, which became necessary devices to enforce certain regulations and to coordinate the economic activities of merchants and of cities. The Kontore of the Hanse had been founded in the cities of Bruges, London, Bergen and Novgorod where Hanseatic merchants shared economic privileges and certain liberties to their own economic benefit. Being the outposts of the Hanse, the 56 57 58 59 Cf. JENKS 2005, p. 39f. Cf. JAHNKE/GRAßMANN 2003. Cf. AFFLERBACH 1993. Cf. VON BRANDT 1963. 15 quite formally defined institution of the Kontore regulated the merchants’ local trading comportement in order to coordinate merchants’ activities and to enforce the privileges against local rulers.60 These markets were vital for the Hanseatic system of trade as a whole inasmuch as they functioned as a kind of gateway for commercial goods being tranferred into and out of the Hanse’s internal market and because Hanseatic commerce was based on the privileges merchants from Lower Germany there once had obtained. Defending these privileges against potential competitors was the main purpose of the Kontore. Hanseatic merchant families therefore had a keen interest to keep up personal contact to compatriots operating there, and almost every Hanseatic merchant who traded inside the Hanse had commercial relationships to at least one of Kontore, usually with friends or relatives living there.61 So it was primarily in interest of merchants, that the vital privileges were kept to. By the middle of the fourteenth century a second Hanseatic formal institution had emerged with the constitution of the Hanseatic League as an alliance of many Hanseatic cities. The Hanseatic League never really had a headquarters’ function for Hanseatic trade, but it can be seen as an attempt to create a sort of a political superstructure of the Hanse and it was, in theory at least, a necessary device, to coordinate the economic and political interests of Hanseatic towns and cities. The towns, and in particular its councils, were needed, to enforce certain juridical pratices promoting the merchants’ informal cooperations, such as always backing a responsible dealing with a trading partner’s goods, for example. Towns also provided a standardisation of weights and measures in order to reduce the transaction costs of trade. So again, it was primarily in the interest of the merchants’ community, that Hanseatic towns and cities formed an association and took on these duties. For Hanseatic merchants both the Kontore and the Hanseatic League worked not as self-enforcing institutions insofar as they were based on formal regulations and as participation within these institutions was regulated by exactly these formal rules. Quite the reverse, these two institutions being based to a large degree on formal definitions were in a sense needed to enforce other regulations inside the Hanseatic system of trade like those on the liability for losses and damages in sea transportation or those on the quality control of products. Interestingly enough, it was this rather formal part of the Hanse that had the largest and most lasting impact on historiography, 60 61 Cf. GREIF/MILGROM/WEINGAST 1994; STREB 2004. Cf. SPRANDEL 1984, p. 29. 16 making generations of historians wrongly believing that the Hanse was a huge trading trust or a mercantile empire. A more plausible interpretation of the Hanse would be that of a pressure group or a distributional coalition promoting long-distance trade and redistributing wealth to its own interest.62 Some structural deficits: possible reasons for the failure of the Hanse in early modern times At the turn of the fifteenth century however, the commercial advantages Hanseatic merchants possessed in the Baltic nevertheless were almost rapidly ceasing. This failure of the system as a whole was path-dependent63 insofar as exactly those strategies which had been employed successfully at earlier stages in the history of the Hanse then turned into a severe hindrance to a further sustained growth of their trading system.64 Thus, the last issue to be pointed to in this analysis will be a brief discussion of possible reasons for the final failure of the Hanseatic trading system. Network size, cultural borders and the network paradox It is a well-established fact of sociological research and network studies, that networks which are based on cultural bonds are hardly able to incorporate members who are lacking these commonly accepted values and that they cannot be expanded beyond a certain group size without attracting free-riders in great numbers due a resulting misfunction of the underlying reputation mechanism. This of course holds also for the Hanse. It was in a sense a »small world«, but only for Hanseatics. To strangers, however, the Hanse must have appeared as a closed society, nearly impossible to reach, and in fact, it really was. The negative effect of self-containment is quite typical for networks based on cultural identity. The Florentine banker Gherardo Bueri is one of the rare exceptions to this rule, because he managed to settle with his business in Lübeck. It was only after he had married into a rich local family, that he also could join a Hanseatic network.65 Since Hanseatic merchants very strictly hold on to the privileges of the Hanse in London, Bruges, Bergen and Novgorod, and since the multilateral reputation mechanism only worked to perfection in smaller or medium-size networks, it was quite difficult for them to expand beyond the borders 62 Cf. IRSIGLER 1989, p. 518; SCHONEWILLE 1998. See on the theoretical concept of path-dependency, a paradigm which is discussed in economic theory for some time already, for instance ARTHUR 1989; DAVID 1994; SYDOW/SCHREYÖGG/KOCH 2005; PUFFERT 2006. 64 Cf. SELZER/EWERT 2005; EWERT/SELZER 2007, 2009a, 2009c. 63 17 of a settled network-based trading system that had been working for so many generations with so great success. Moreover, there is some evidence, that the so-called network paradox appears in the example of the Hanseatic merchants’ network organisation. The network paradox describes the divergence of the Figure 2: The network paradox organisational design on the one NETWORK ORGANISATION hand side, and the actual pattern in which the members of an orTHEORY ORGANISATIONAL DESIGN BUREAUCRATIC ORGANISATION formal hierarchy ganisation cooperate with each other on the other hand. Bureaucratic organisations are network structure erachies, but in reality social REALITY STRUCTURE OF COOPERATION based by design on formal hi- informal network clusters and hierarchies networks do matter very much indeed, as they often allow for a much quicker and more efficient dealing with tasks. Like- Cross-classification of the type of organisation and intended vs. actual structure of cooperation inside the organisation. Graph developed following ADERHOLD/MEYER 2003. wise, organisational design and the actual cooperation pattern can differ tremendously in a network organisation. Although implemented with the intention to enable loose and flexible cooperation in the best interest of all members, a network organisation can easily turn into a fragmentary group of clusters with a quasi-petrified formal and hierarchical structure (see Figure 2).66 The following three points underline the relevance of the network paradox in the Hanse case67: firstly, the Hanseatic habit of predominantly cooperating with family members and friends put under threat the flexible and variable character the commercial network in general had. Although in most cases merchants of the same family in principle operated independently at distant locations all across the catchment area of the Hanse, family bonds could very well create areas with an asymmetrical distribution of power within the network. Secondly, the question of reputation and trust as cooperation enhancing mechanisms arises, as commonly activities of network members through these means only could be coordinated with both trust and reputa65 66 Cf. FOUQUET 1998. Cf. ADERHOLD/MEYER 2003. 18 tion being already existent. The building process of course took time, and once trust and reputation had been built up, in most circumstances it would have been a nonefficient decision for merchants not to capitalise these means. Nevertheless, using reputation for commercial purposes and relying on trustworthy partners only definitely increased the likelihood of sticking with virtually the same set of trading relationships, which in turn meant that the whole commercial network became fragmentary. And in fact, despite trading goods with quite a number of commercial partners, hanseatic merchants nonetheless usually held on to these already established core partnerships for quite a long time. Finally, for exactly the same reason the concept of the so-called »cooptition« has to be taken cautiously, although hanseatic merchants in contrast to their competitors from Upper Germany never really had forbidden cross competition inside their networks.68 It follows, that »cooptition« may be a brilliant idea in theory, but for late medieval Hanseatic merchants a rather poor concept to put into practice. The multiplicity of structure Besides the fact, that Hanseatic businesses were quite small in size and thus had themselves to adapt to a given heterogeneous context, the Hanse’s commercial exchange was embedded in the several overlapping organisational layers – traders’ networks, Kontore, Hanseatic cities and the Hanseatic League. The likelihood of potential conflicts between individual interests of merchants and collective interests of town communities and of the Kontore presumably increased even more after the formation of the Hanseatic League. The Kontore as being the institutions to enforce privileges were not controlled by a central instance. Quite the reverse, often they developed own trade policies, which then counteracted the objectives of merchants and also the policies of Hanseatic towns. The Hanseatic League itself thoroughly had own economic and political scopes and very strictly attempted to get these interests accepted not only by foreign traders but also by the Hanseatic merchants themselves.69 Originally designed to coordinate merchants’ interests, to oversee trade and to provide enforcement for privileges and for trade regulations, it was this multiplicity of structure itself, that put a further constraint on the activities of Hanseatic mer- 67 68 69 For this see also SELZER/EWERT 2001; EWERT/SELZER 2006. Cf. SPRANDEL 1984. Cf. SPRANDEL 1984, p. 31f. 19 chants.70 The emergence of the Hanseatic League furthermore points to the problems of collective action and the instability of cartels. It was foreseeable, that a powerful member of this cartel, namely Lübeck, took over to prevent its dissolution.71 As the economic and political scopes of the Kontore in Bruges, London, Bergen and Novgorod, and those of particular Hanseatic towns and the Hanseatic League sometimes were conflicting, merchants got more and more trapped by the negative effects of this multiplicity of structure. This of course could create situations in which single merchants came into conflict with higher order economic interests, for instance when having been confronted with the Hanse’s typical ban on the formation of business partnerships with non-hanseatic traders.72 Especially, this seems to have been the case during embargoes. During the Hanseatic blockade of Flanders from 1358 to 1360 for instance, by neglecting to respect the prohibition of trade the traders of the town of Kampen tried to profit from circumstances.73 The change of economic conditions Exogenous and endogenous changes in the commercial environment to which the Hanse’s network organisation originally had been so well adapted obviously put this trading system severely under pressure at the turn of the fifteenth century. Firstly, the merchants’ potential to remain flexible at the cost of a still lacking development of the capital market structure within the inner reach of the Hanseatic trading system, meant that Hanseatic merchants, other than their non-Hanseatic competitors, had almost no access to risk capital which nonetheless would have been urgently needed for much bigger commercial endeavours than those typically undertaken in the internal Hanseatic trade.74 Secondly, the Hanse’s policy to block opponents on the grounds of the privileges and liberties its merchants enjoyed in Bruges hindered both of them to realise early enough that the economic importance of the Bruges market had been rapidly declining with the rise of the Antwerp market in the second half of the fifteenth century. And finally, harmonisation of course reduced transaction costs inside the Baltic for Hanseatic merchants, facilitating their trading operations a lot. So much is true. Yet, the external effect of this were lower transaction costs for nonHanseatic merchants as well. As a consequence, the commercial competitors of the 70 71 72 73 Cf. VON BRANDT 1963. See for a description of this economic phenomenon in a medieval setting VOLCKART 2004. Cf. SPRANDEL 1984, p. 32f.. Cf. FRICCIUS 1932/33. 20 Hanse were able to intrude the Hanseatic system of trade by the end of the fifteenth century, and they put a serious threat to the privileged commercial position Hanseatic merchants had enjoyed in the Baltic so far. Conclusions By applying the concept of network and of virtual organisation to the late medieval Hanse it becomes clear, that »network« is not a fashionable term only, but a very powerful theoretical concept indeed. Opposite to shortcomings in the literature on the Hanse, with this concept the trading pattern that had evolved from the exchange relationships between hanseatic merchants is explained by purely economic motivations of the agents involved in this trading system. Moreover, the model of virtual organisation enables to describe in a more adequate manner than before the paradox that the Hanse could provide consumers everywhere in the Baltic with a wide range of goods on the one hand side, but on the other hand did not rely on any complex formal hierarchical or company-like structure while doing this. The explanatory power of the network concept becomes evident insofar as some of the strengths and the weaknesses of a network structure that are discussed in the literature on business networks can be illustrated with Hanse example. The hanseatic merchants had to deal with the fact that a lasting commitment to mutual cooperation in principle was irreconcilable with the flexibility of their couplings. As is the case with modern network organisations, they reacted to this by establishing long-term cooperations based on reputation and trust, which in the case of commercial transactions inside families very well could turn into asymmetrical relationships and then fostered the network’s partial segregation into separate clusters. Yet, the Hanse example cannot be taken only to confirm theory or for illustrating its weaknesses. The pattern of reciprocal cooperations shows that a virtual organisation was a possible and in addition to that also efficient solution to the problems of availability and transmission of information that were typical for the late Middle Ages. These information and coordination problems could only be coped with because the network pattern was embedded in an institutional environment that provided the merchants with standardisation and promoted their informal cooperation. Taken all in all, it seems obvious that the late medieval Hanse was neither a cities’ state nor a commercial super trust. The model of network or virtual organisation is a 74 Cf. SCHONEWILLE 1998. 21 more realistic approach to the Hanse and its trade. Institutional economics issues such as transaction costs, principal-agents-relationships, the role of trust and reputation or the stability of cartels are important for an economic interpretation of the late medieval Hanse. Finally, the Hanse’s inability to expand and its decreasing competitiveness at the turn of the fifteenth century were in a sense path-dependent, because they were triggered by a trading system that predominantly relied on a network organisation. It was exactly because structure and institutional context were very well matched and were perfectly working together, that potentials to develop and to expand the system could not be realised. Certainly, this particular cost arising with the implementation of a network structure was responsible for the Hanse’s decline in the early modern period. References Jens ADERHOLD, Matthias MEYER, Netzwerke richtig verstehen – zur Relevanz von Potentialität (Netzwerk) und Aktualität (Kooperation), in: Egon MÜLLER (ed.), Vernetzt planen und produzieren – VPP 2003. Tagungsband 22.–23.09.2003, SFB 457, Chemnitz 2003, pp. 153–157. Thorsten AFFLERBACH, Der berufliche Alltag eines spätmittelalterlichen Hansekaufmanns (Kieler Werkstücke A7), Frankfurt/Main 1993. W. Brian ARTHUR, Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-in by Historical Events, in: The Economic Journal 99 (1989), pp. 116-131. Robert AXELROD, The Evolution of Cooperation, New York 1984. Clemens BAUER, Unternehmung und Unternehmungsformen im Spätmittelalter und in der beginnenden Neuzeit (Münchner Volkswirtschaftliche Studien N.F. 23), Jena 1923. Thilo C. BECK, Cooptition bei der Netzwerkorganisation, in: Zeitschrift für Organisation 67 (1998), pp. 271–276. Dick E. H. DE BOER et al. (eds.), »... in guete freuntlichen nachbarlichen verwantnus und hantierung ...«. Wanderung von Personen, Verbreitung von Ideen, Austausch von Waren in den niederländischen und deutschen Küstenregionen vom 13. bis 18. Jahrhundert (Oldenburger Schriften zur Geschichtswissenschaft 6), Oldenburg 2001. Ahasver VON BRANDT, Die Hanse als mittelalterliche Wirtschaftsorganisation. Entstehen, Daseinsformen, Aufgaben, in: ID. et al. (eds.), Die Deutsche Hanse als Mittler zwischen Ost und West, Cologne, Opladen 1963, pp. 9–38. John CHILD, Trust – The Fundamental Bond in Global Collaboration, in: Organizational Dynamics 29 (2001), pp. 274–288. Ronald H. COASE, The Nature of the Firm, in: Economica NS 4 (1937), pp. 386–405. Ronald H. COASE, The New Institutional Economics, in: Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 140 (1984), pp. 229–231. Albrecht CORDES, Spätmittelalterlicher Gesellschaftshandel im Hanseraum (Quellen und Darstellungen zur hansischen Geschichte N.F. 45), Cologne 1998. Albrecht CORDES, Einheimische und gemeinrechtliche Elemente im hansischen Gesellschaftsrecht des 15.–17. Jahrhunderts. Eine Projektskizze, in: Niels JÖRN, Detlef KATTINGER and Horst WERNICKE (eds.), »kopet uns werk by tyden«. Beiträge zur hansischen und preußischen Geschichte. Festschrift für Walter Stark zum 75. Geburtstag, Schwerin 1999, pp. 67–71. Albrecht CORDES, Wie verdiente der Kaufmann sein Geld? Hansische Handelsgesellschaften im Spätmittelalter (Handel, Geld und Politik 2), Lübeck 2000. 22 Paul A. DAVID, Why are Institutions the ‚Carriers of History‘? Path Dependence and the Evolution of Conventions, Organizations and Institutions, in: Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 5 (1994), pp. 205–220. Andreas DIEKMANN, Soziale Dilemmata. Modelle, Typisierungen und empirische Resultate, in: HansJürgen ANDREß et al. (eds.), Theorie, Daten, Methoden. Neue Modelle und Verfahrensweisen in den Sozialwissenschaften. Theodor Harder zum sechzigsten Geburtstag, Munich 1992, pp. 177–203. Philippe DOLLINGER, Die Hanse, 4th edition, Stuttgart 1989. Sonja DÜNNEBEIL, Die Lübecker Zirkel-Gesellschaft. Formen der Selbstdarstellung einer städtischen Oberschicht (Veröffentlichungen zur Geschichte der Hansestadt Lübeck, B27), Lübeck 1996. Wilhelm EBEL, Lübisches Kaufmannsrecht vornehmlich nach Lübecker Ratsurteilen des 15./16. Jahrhunderts, Göttingen 1957. Ulf Christian EWERT, Stephan SELZER, The Hansa as a Virtual Organisation: Some Historical Remarks on the Network Paradigm, Working Paper, European Social Science History Conference 2006, Amsterdam. Ulf Christian EWERT, Stephan SELZER, Netzwerkorganisation im Fernhandel des Mittelalters: Wettbewerbsvorteil oder Wachstumshemmnis?, in: Hartmut BERGHOFF, Jörg SYDOW (eds.), Unternehmerische Netzwerke. Eine historische Organisationsform mit Zukunft?, Stuttgart 2007, pp. 45–70. Ulf Christian EWERT, Stephan SELZER, Building Bridges, Closing Gaps: The Variable Strategies of Hanseatic Merchants in Heterogeneous Mercantile Environments, in: James M. MURRAY, Peter STABEL (eds.), Bridging the Gap: Problems of Coordination and the Organization of International Commerce in Late Medieval European Cities (Urban History), Turnhout 2009. [forthcoming] [= EWERT/SELZER 2009a] Ulf Christian EWERT, Stephan SELZER, Art. »Social Networks«, in: Don HARRELD (ed.), A Companion to the Hanseatic League, Leiden 2009. [forthcoming] [= EWERT/SELZER 2009b] Ulf Christian EWERT, Stephan SELZER, Wirtschaftliche Stärke durch Vernetzung. Zu den Erfolgsfaktoren des hansischen Handels, in: Mark HÄBERLEIN, Christof JEGGLE (eds.), Praktiken des Handels. Geschäfte und Beziehungen europäischer Kaufleute in Mittelalter und früher Neuzeit (Irseer Schriften N.F. 6), Konstanz 2009. [fortcoming] [= EWERT/SELZER 2009c] Gerhard FOUQUET, Ein Italiener in Lübeck. Der Florentiner Gherardo Bueri (gest. 1449), in: Zeitschrift des Vereins für Lübeckische Geschichte und Altertumskunde 78 (1998), pp. 187– 220. W. FRICCIUS, Der Wirtschaftskrieg als Mittel hansischer Politik im 14. und 15. Jahrhundert, in: Hansische Geschichtblätter 57 (1932), pp. 38-77; 58 (1933), pp. 52-121. Joseph GALASKIEWICZ, The “New Network Analysis” and its Application to Organizational Theory and Behavior, in: Dawn IACOBUCCI (ed.), Networks in Marketing, Thousand Oakes, London, New Delhi 1996, pp. 19–31. Yadira GONZÁLES DE LARA, The Secret of Venetian Success: A Public Order, Reputation-based Institution, in: European Review of Economic History 12 (2008), pp. 247–285. Avner GREIF, Institutions and International Trade: Lessons from the Commercial Revolution, in: American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 82 (1992), pp. 128–133. Avner GREIF, Contract Enforceability and Economic Institutions in Early Trade: The Magribi Traders’ Coalition, in: American Economic Review 83 (1993), pp. 525-548. Avner GREIF, The Fundamental Problem of Exchange. A Research Agenda in Historical Institutional Analysis, in: European Review of Economic History 4 (2000), pp. 251–284. Avner GREIF, Institutions and Trade during the Late Medieval Commercial Revolution: A Game Theoretical Approach, New York 2004. Avner GREIF, Paul MILGROM, Barry R. WEINGAST, Coordination, Commitment, and Enforcement: The Case of the Merchant Guild, in: Journal of Political Economy 41, 1994, pp. 745–776. 23 Anke GREVE, Fremde unter Freunden – Freunde unter Fremden? Hansische Kaufleute im spätmittelalterlichen Brügger Handelsalltag, in: Stephan SELZER, Ulf Christian EWERT (eds.), Menschenbilder – Menschenbildner. Individuum und Gruppe im Blick des Historikers (Hallische Beiträge zur Geschichte des Mittelalters und der Frühen Neuzeit 2), Berlin 2002, pp. 177188. Chris GREY, Christina GARSTEN, Trust, Control and Post-bureaucracy, in: Organization Studies 22 (2001), pp. 229–250. Håkan HÅKANSSON, D. Deo SHARMA, Strategic Alliances in a Network Perspective, in: Dawn Iacobucci (ed.), Networks in Marketing, Thousand Oakes, London, New Delhi 1996, pp. 108– 124. Rolf HAMMEL-KIESOW, Die Hanse, Munich 2000. Reinhard HILDEBRANDT, Diener und Herren. Zur Anatomie großer Unternehmen im Zeitalter der Fugger, in: Johannes BURKHARDT (ed.), Augsburger Handelshäuser im Wandel des historischen Urteils (Colloquia Augustana 3), Berlin 1996, pp. 149–174. Reinhard HILDEBRANDT, Unternehmensstrukturen im Wandel. Personal- und Kapitalgesellschaften vom 15.–17. Jahrhundert, in: Hans Jürgen GERHARD (ed.), Struktur und Dimension. Festschrift für Karl-Heinrich Kaufhold zum 65. Geburtstag, vol. 1: Mittelalter und Frühe Neuzeit (Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Beihefte 132), Stuttgart 1997, pp. 93–110. Volker HENN, Die Hanse: Interessengemeinschaft oder Städtebund? Anmerkungen zu einem neuen Buch, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 102 (1984), pp. 119-126. Otfried HÖFFE, Spieltheorie und Herrschaftsfreiheit, in: Soziologische Revue 11 (1988), pp. 384–392. Anne ILLINITCH et al., New Organisational Forms and Strategies for Managing in Hypercompetitive Environment, in: Organization Science 7 (1996), pp. 211–220. Franz IRSIGLER, Der Alltag einer hansischen Kaufmannsfamilie im Spiegel der Veckinchusen-Briefe, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 103 (1985), pp. 75-99. Franz IRSIGLER, Der hansische Handel im Spätmittelalter, in: Jörgen BRACKER (ed.), Die Hanse. Lebenswirklichkeit und Mythos. Katalog der Ausstellung im Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte 1989, Lübeck 1989, pp. 518-532. Carsten JAHNKE, Antjekathrin GRAßMANN, Seerecht im Hanseraum des 15. Jahrhunderts. Edition und Kommentar zum Flandrischen Copiar Nr. 9 (Veröffentlichungen zur Geschichte der Hansestadt Lübeck B36), Lübeck 2003. Stuart JENKS, Transaktionskostentheorie und die mittelalterliche Hanse, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 123, pp. 31-42. Gareth R. JONES, Transaction Costs, Property Rights, and Organizational Culture: An Exchange Perspective, in: Administrative Science Quarterly 28 (1983), pp. 454–467. Robert KRAUT et al., Coordination and Virtualization: The Role of Electronic Networks and Personal Relationships, in: Organization Science 10, 1999, pp. 722–740. Sybille LEHMANN, A Rent Seekers’ Paradise, or Why There Was No Revolution in Fifteenth- to Eighteenth-Century Nuremberg, in: Oliver VOLCKART (ed.), The Institutional Analysis of History (Homo Oeconomicus XXI/1 – Sonderheft), Munich 2004, pp. 41–57. Charlotte LINK, Daniela KAPFENBURGER, (2005), Transaktionskostentheorie und hansische Geschichte. Danzigs Seehandel im 15. Jahrhundert im Licht einer volkswirtschaftlichen Theorie, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 123 (2005), pp. 153-169. Robert S. LOPEZ, The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages, 950–1350, Cambridge 1976. Gunnar MICKWITZ, Neues zur Funktion hansischer Handelsgesellschaften, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 62 (1937), pp. 191-201. Gunnar MICKWITZ, Aus Revaler Handelsbüchern. Zur Technik des Ostseehandels in der ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts (Societas Scientiarum Fennica. Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum IX/5), Helsingfors 1938. Nitin NOHRIA, Introduction: Is a Network Perspective a Useful Way of Studying Organizations in: Nitin NOHRIA and Robert G. ECCLES (eds.), Networks and Organizations. Structure, Form, and Action, Boston 1992, pp. 1–22. 24 Douglass C. NORTH, Institutions, in: Journal of Economic Perspectives 5 (1991), pp. 97–112. Richard N. OSBORN and John HAGEDOORN, The Institutionalisation and Evolutionary Dynamics of Inter-organisational Alliances and Networks, in: Academy of Management Journal 40 (1997), pp. 261–278. Angelo PICHIERRI, Die Hanse – Staat der Städte, Opladen 2000. Ernst PITZ, Bürgereinung und Städteeinung. Studien zur Verfassungsgeschichte der Hansestädte und der deutschen Hanse (Quellen und Darstellungen zur hansischen Geschichte 52), Cologne et al. 2001. Walter W. POWELL, Neither Market nor Hierarchy: Network Forms of Organization, in: Research in Organisational Behaviour 10 (eds. L. L. CUMMINGS and B. M. STAW), Greenwich 1990, pp. 295–336. Douglas PUFFERT, Paths Through History: Contingency in Economic Outcomes, Working Paper, European Social Science History Conference 2006, Amsterdam. Anatol RAPOPORT, Contributions of Experimental Games to Mathematical Sociology, Hans-Jürgen ANDREß et al. (eds.), Theorie, Daten, Methoden. Neue Modelle und Verfahrensweisen in den Sozialwissenschaften. Theodor Harder zum sechzigsten Geburtstag, Munich 1992, pp. 165– 176. Michael I. REED, Organization, Trust, and Control: A Realist Analysis, in: Organization Studies 22 (2001), pp. 201–228. Joachim RIEBARTSCH, Augsburger Handelsgesellschaften des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts. Eine vergleichende Darstellung ihres Eigenkapitals und ihrer Verfassung, Bergisch Gladbach 1987. Tanja RIPPERGER, T.: Ökonomie des Vertrauens. Analyse eines Organisationsprinzip, Tübingen 1998. Gerrit ROOKS et al., How Inter-firm Co-operation Depends on Social Embeddedness: A Vignette Study, in: Acta Sociologica 43 (2000), pp. 123–137. Jefferey M. SCHELLERS, Transnational Urban Associations and the State in Contemporary Europe: A Rebirth of the Hanseatic League, in: Jahrbuch für Europäische Verwaltungsgeschichte 15 (2003), pp. 289–308. Christian SCHOLZ, Virtuelle Organisation: Konzeption und Realisation, in: Zeitschrift für Organisation 65 (1996), pp. 204–210. Mark SCHONEWILLE, Hanse Theutonicorum, Groningen 1997. Mark SCHONEWILLE, Risk, Institutions and Trade. New Approaches to Hanse History, Working Paper, Nijmwegen 1998. Roswitha SCHWEICHEL, Kaufmännische Kontakte und Warenaustausch zwischen Köln und Brügge. Die Handelsgesellschaft von Hildebrand Veckinchusen, Werner Scherer und Reinhard Noiltgin, in: DE BOER et al. 2000, pp. 341-358. Stephan SELZER, Artushöfe im Ostseeraum. Ritterlich-höfische Kultur in den Städten des Preußenlandes im 14. Jahrhundert (Kieler Werkstücke, D8), Frankfurt/Main et al. 1996. Stephan SELZER, Trinkstuben als Orte der Kommunikation. Das Beispiel der Artushöfe im Preußenland (ca. 1350–1550), in: Gerhard FOUQUET, Matthias STEINBRINK and Gabriel ZEILINGER (eds.), Geschlechtergesellschaften, Zunft-Trinkstuben und Bruderschaften in spätmittelalterlichen und frühneuzeitlichen Städten (Stadt in der Geschichte, 30), Stuttgart 2003, pp. 73–98. Stephan SELZER, Ulf Christian EWERT, Verhandeln und Verkaufen, Vernetzen und Vertrauen. Über die Netzwerkstruktur des hansischen Handels, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 119 (2001), pp. 135–161. Stephan SELZER, Ulf Christian EWERT, Die Neue Institutionenökonomik als Herausforderung an die Hanseforschung, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 123 (2005), pp. 7–29. Stephan SELZER, Ulf Christian EWERT, Netzwerke im europäischen Handel des Mittelalters: Konzepte – Anwendungen – Fragestellungen, in: Gerhard FOUQUET, Hans-Jörg GILOMEN (eds.), Netzwerke im europäischen Handel des Mittelalters (Vorträge und Forschungen), Ostfildern 2009. [fortcoming] Rolf SPRANDEL, Die Konkurrenzfähigkeit der Hanse im Spätmittelalter, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 102 (1984), pp. 21–38. 25 Udo STABER, Steuerung von Unternehmensnetzwerken: Organisationstheoretische Perspektiven und soziale Mechanismen, in: Jörg SYDOW, Arnold WINDELER (eds.), Steuerung von Netzwerken. Konzepte und Praktiken, Wiesbaden 2000, pp. 58-87. Walter STARK, Über Platz- und Kommissionshändlergewinne im Handel des 15. Jahrhunderts, in: Konrad FRITZE, Eckhard MÜLLER-MERTENS, Walter STARK (eds.), Autonomie, Wirtschaft und Kultur der Hansestädte (Hansische Studien 6), Weimar 1984, pp. 130–146. Walter STARK, Untersuchungen zum Profit beim hansischen Handelskapital in der ersten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts (Abhandlungen zur Handels- und Sozialgeschichte 24), Weimar 1985. Walter STARK, Über Techniken und Organisationsformen des hansischen Handels im Spätmittelalter, in: Stuart JENKS, Michael NORTH (eds.), Der hansische Sonderweg? Beiträge zur Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Hanse, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 1993, pp. 191–201. Wilhelm STEIN, Handelsbriefe aus Riga und Königsberg von 1458 und 1461, in: Hansische Geschichtsblätter 9.2 (1898), pp. 59–125. Jochen STREB, Die politische Glaubwürdigkeit von Regierungen im institutionellen Wandel. Warum ausländische Fürsten das Eigentum der Fernhandelskaufleute der Hanse schützten, in: Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 2004/1, pp. 141–156. Wolfgang VON STROMER, Organisation und Struktur deutscher Unternehmen in der Zeit bis zum Dreißigjährigen Krieg, in: Tradition 13 (1968), pp. 29–37. Jörg SYDOW, Georg SCHREYÖGG, J. KOCH, Organizational Paths: Path Dependency and Beyond, Working Paper 2005. Leigh TESFATSION, A Trade Network Game with Endogenous Partner Selection, in: Hans AMMAN, Berc RUSTEM and Andrew WHINSTON (eds.), Computational Approaches to Economic Problems (Advances in Computational Economics 6), Dordrecht, Boston, London 1997, pp. 249– 269. Hildegard THIERFELDER, Rostock-Osloer Handelsbeziehungen im 16. Jahrhundert. Die Geschäftspapiere der Kaufleute Kron in Rostock und Bene in Oslo (Abhandlungen zur Handels- und Sozialgeschichte 1), Weimar 1958. Grahame F. THOMPSON, Between Hierachies and Markets: The Logic and Limits of Network Forms of Organization, Oxford 2003. Cyril TOMKINS, Interdependencies, Trust and Information in Relationships, Alliances and Networks, in: Accounting, Organizations and Society 26 (2001), pp. 161–191. Oliver VOLCKART, Die Dorfgemeinde als Kartell: Kooperationsprobleme und ihre Lösungen im Mittelalter und in der frühen Neuzeit, in: Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 2004/2, pp. 189– 203 Duncan WATTS, Networks, Dynamics, and the Small-World Phenomenon, in: American Journal of Sociology 105 (1999), pp. 493–527. Oliver E. WILLIAMSON, Transaction-Costs Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations, in: Journal of Law and Economics 22 (1979), pp. 233–261. Horst WERNICKE, Die Städtehanse, 1280–1418. Genesis – Strukturen – Funktionen (Abhandlungen zur Handels- und Sozialgeschichte 22), Weimar 1983. Arnold WINDELER, Unternehmensnetzwerke. Konstitution und Strukturation. Wiesbaden 2001. Harald WITTHÖFT, Waren, Waagen und Normgewichte auf den hansischen Routen bis zum 16. Jahrhundert, in: Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte 112 (1976), pp. 184-202. Birgitta WOLF, Thomas GRAßMANN, Art. »Vertragstheorie«, in: Georg SCHREYÖGG, Axel von WEBER (eds.), Handwörterbuch Unternehmensführung und Organisation, 4th edition, Stuttgart 2004, col. 1587–1595. T. WOLF, Tragfähigkeiten, Ladungen und Maße im Schiffsverkehr der Hanse (Quellen und Darstellungen zur hansischen Geschichte N.F. 31), Cologne 1986. 26