1 | 2011 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid

Edited by: Peter PA Smyth, UCD, Dublin · Published by: Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany

1 | 2011

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules

Mahmood Gharib, Hossein Gharib

Thyroid International 1 2011

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules

Mahmood Gharib, BA and Hossein Gharib, MD, MACP, MACE

Mahmood Gharib, B.A.

Visiting Medical Student

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Hossein Gharib, M.D., MACP, MACE

Professor of Medicine

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

From Mayo Clinic

The Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism and Nutrition

200 First Street SW

Rochester, MN 55903

2 Thyroid International 1 2011

Mahmood Gharib, BA received his B.A. from Emory

University in 2005, and is now a third year medical student at St George's University

Medical School. He is currently a visiting medical student at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine.

Reprints: Hossein Gharib, MD, Division of Endocrinology,

Diabetes, Metabolism, and Nutrition, Mayo Clinic, 200

First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905 (gharib.hossein@ mayo.edu).

Hossein Gharib, MD, MACP,

MACE is the Past President of

AACE & American College of

Endocrinology and Professor of Medicine at the Mayo

Clinic College of Medicine.

Dr. Gharib, has a graduate of the University of Michigan

Medical School, completed his internal medicine and endocrine training at the

Mayo Clinic where he has served as a consultant in the

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Nutrition, and

Metabolism for the past four decades.

He is an international authority on thyroid disorders, he has lectured at over 300 national and international endocrine meetings. He has authored or coauthored more than 250 academic papers, including peerreviewed journal articles, scientific meeting abstracts, and book chapters. Dr. Gharib has served on the editorial boards of JCEM and Endocrine Practice, and is a member of editorial boards of Thyroid, Acta

Endocrinologica (Romania), and International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. He coauthored the first Evidence-Based Endocrinology textbook in 2003, reprinted in 2008.

His many honors include being recognized with a

Mastership from both the American College of Physicians

(MACP) and the American College of Endocrinology

(MACE). He is the recipient many awards including the

Paul Starr Award of the American Thyroid Association, the International Clinician Award of the Associazione

Medici Endocrinologi, the Distinction Award of the

Brazilian Society of Endocrinology & Metabolism, and the prestigious Distinguished Physician Award of the

Endocrine Society in 2010.

Thy roid Inter na tional

Editor-in-Chief: Peter PA Smyth, UCD, Dublin

This is the title of a pub li ca tion series by Merck KGaA,

Darm stadt, Germany. We are pub lish ing papers from renowned inter na tional thy roid experts in order to pass on the exten sive expe ri ence which the authors pos sess in their field to a wide range of phy si cians dealing with the diagnosis and ther apy of thy roid dis eases.

Respon sible at Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany:

Gernot Beroset

Thy roid Inter na tional · 1–2011

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, D-64271 Darm stadt

ISSN 0946-5464

H t Thyr idology

ETA’s journal on hot and controversial topics

Free access:

www.hotthyroidology.com

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules 3

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules

Introduction

Clinical practice guidelines are developed to facilitate decision making and improve standards of care. The process usually begins with a professional society, an institution, or a government agency selecting a panel of experts in a given field to develop a document to enhance quality of care. It is generally accepted that this process must follow transparent procedures, be without for-profit support, with the panel having no significant conflicts of interests. Guideline recommendations should be clear, concise, evidence-based, and clinically useful. It should be noted that while these recommendations are based on the best available evidence, they are to supplement, not replace, good clinical judgment.

In 2010, the American Association of Clinical

Endocrinologists (AACE), the Associazione Medici

Endocrinologi (AME), and the European Thyroid

Association (ETA) prepared and published clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules with graded recommendations using the best evidence level.

1 This document was unique because it resulted from a consensus among AACE,

AME, and ETA primary writers, task force members, and reviewers, representing different practice patterns on the 2 sides of the Atlantic.

This article highlights some of these suggestions using typical clinical cases to illustrate application of tests, risk factor-based management, and novel treatment.

The format consists of a case presentation followed by a brief discussion of main or controversial issues regarding tests and treatment, using recommendations from the current guidelines.

How common is this problem?

The reported prevalence of thyroid nodules is quite variable, depending on the population studied and the methods used to study. For example, nodules are discovered by thyroid palpation in 3% to 7%, by ultrasound (US) exam in 20% to 70%, and by autopsy studies in 50% of the general population.

2-5 Prevalence of thyroid nodules increases with iodine deficiency, ionizing radiation, and increasing age; nodules are more common in women than in men. The annual incidence is around 0.1% which translates into more than 300,000 new nodules each year in the United States. Information from regions outside North America is similar, being influenced by the factors noted above. Based on these data, it is reasonable to conclude that thyroid nodules constitute a very common clinical problem.

4 Thyroid International 1 2011

Clinical Cases

Case 1: Solitary Nodule

A 29-year-old woman is referred for evaluation after a thyroid nodule was discovered during a routine physical examination. She reports no neck pain or pressure. There are no symptoms of hyper- or hypothyroidism. She has no family history of thyroid cancer and there is no history of childhood neck radiation. On physical examination, there is a 2.0 × 2.0 cm firm, nontender, left thyroid nodule. Right thyroid was normal and there is no cervical adenopathy.

Is this nodule truly solitary?

US examination not only delineates the features of a nodule, it sometimes detects unsuspected nodule(s) in the gland when only one thyroid nodule is noted clinically.

For example, a Mayo Clinic study 6 showed 151 patients presenting with a clinically solitary nodule and US examination revealed one or more “extra” nodules in 48% of patients. In approximately one-third of patients there were 2 or more nodules missed on physical examination.

As would be expected, nodules not palpated were smaller than 1 cm in diameter. The incidental finding of thyroid nodules in patients undergoing carotid screening, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomo graphy imaging for cancer staging, or neck computed tomography now represents a common practice issue. Thyroid incidentalomas are frequently small (<1.5 cm), asymptomatic, and benign. However, the discovery of a thyroid incidentaloma is associated with anxiety for the patient and a management challenge for the endocrinologist.

7,8

What are predictors of malignancy in this nodule?

Certain features in history and physical examination favor malignancy including childhood neck radiation; family history for thyroid cancer; male sex; young or old age; a firm, fixed nodule; and enlarged neck nodes

(Table 1).

Nodules presenting in childhood or adolescence should always be regarded with caution because of increased risk for malignancy in this age group.

Two recent studies suggest that serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels can influence the risk of

Table 1 Predictors of Thyroid Nodule Malignancy by

History and Physical Examination

• History of childhood head-neck radiation

• Family history of hereditary thyroid cancer

(PTC, MTC, MEN 2)

• Male sex

• Age < 20 or >70 years

• Firm, fixed nodule

• Ipsilateral cervical adenopathy

• Vocal cord paralysis

PTC: Papillary thyroid carcinoma; MTC: Medullary thyroid carcinoma; MEN2:

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2

Table 2 Ultrasound Features of Thyroid Nodule Favoring

Malignancy

• Solid, hypoechoic

• Irregular margins

• Microcalcifications

• Chaotic or increased vascularity (Doppler)

• Tall > wide

• Extracapsular growth

Table 3 2010 Thyroid Nodule Guidelines

Cytologic Classification

Cytology Risk of cancer, %

1. Nondiagnostic

2. Benign

< 3

< 1

3. Follicular neoplasm < 10

4. Suspicious for malignancy 50

5. Malignant > 99 cancer with higher levels being associated with increased risk.

9,10 In one report, a solitary nodule with a serum

TSH level of 6 mIU/L had a 3-fold increased risk of cancer than if TSH was 0.3.

9 Contrary to previous experience that large and/or solitary nodules are more likely malignant, recent data show that neither nodule size nor nodule number influences cancer risk.

11

The guidelines recommend thyroid US for patients suspected of having a nodule, those with a palpable nodule or a multinodular goiter, or patients at high risk for thyroid cancer (familial thyroid cancer or previous neck irradiation). US will provide additional information such

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules 5 as detection of unsuspected nodules, accurate measurement of nodule dimensions, and show nodule characteristics that may determine risk of malignancy.

11-14 Some

US features that favor malignancy are listed in Table 2.

The specificity for cancer approaches 90% when 2 or more suspicious US features are present. Microcalcifications, the hallmark of papillary thyroid carcinoma, are highly predictive of cancer. Color Doppler flow evaluates nodule vascularity with increased or chaotic vascularity being another feature that favors malignancy.

15 Additionally,

US is valuable for guiding fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy and provides accurate measurement of nodule size that can be used for follow-up evaluation.

11,16,17

What tests are necessary?

Serum TSH should be ordered to determine thyroid function. If TSH is normal, free thyroxine (FT4) determination is not necessary. If TSH is high, FT4 and thyroperoxidase antibody titer should be measured. If

TSH is low, FT4 and FT3 should be ordered for possible identification of hyperthyroidism, followed by a radioisotope scan. If the scan shows a hyperfunctioning nodule, there is no need for FNA. However, it should be emphasized that in the new paradigm of nodule evaluation an isotope scan is seldom used.

Serum calcitonin (Ct) is a recognized marker for C-cell disease and elevated levels are seen in patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma. A number of studies have reported abnormal serum Ct levels in patients with nodular thyroid disease due to small medullary thyroid carcinoma lesions.

18-20 Therefore, routine measurement of basal serum Ct in patients presenting with nodular thyroids has been proposed by some to detect early, unsuspected medullary thyroid carcinoma, an issue that still remains controversial. Although the previous

AACE-AME guidelines did not endorse this practice, the revised 2010 guidelines favors, but does not recommend, routine Ct testing: “measurement of basal serum calcitonin level may be useful in the initial evaluation of thyroid nodules”.

1

As noted above, US and FNA are now integral parts of nodule work up, with cytologic examination being necessary to confirm if a lesion is benign or malignant.

FNA biopsy can be performed either by palpation or preferably by US-guidance. In clinics with experience,

FNA biopsy is a highly reliable test with an accuracy rate better than 95%.

11,13,21-25 FNA biopsy is considered a relatively simple, safe, and cost-effective technique with best results obtained when an experienced endocrinologist performs the biopsy and an expert cytopathologist interprets the smears. The use of US-guided

FNA increases the accuracy of results. In contrast to the

2006 guidelines, 26 the current document has adopted the use of a 5 cytologic category listed in Table 3. In general, risk of cancer in a benign or negative cytology is less than 1%, in a suspicious cytology is about 50%, and in a malignant report is 99%.

25

What are management options?

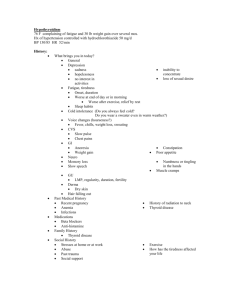

In this patient serum TSH was 1.5 mIU/L, US showed a solid, hypoechoic nodule without features suspicious for malignancy, and FNA was benign, consistent with a colloid nodule (Figure 1). The guidelines recommend observation with follow-up US examination in 6 to 18 months. Routine use of T4 suppressive therapy is discouraged.

27 The guidelines do mention that occasionally T4 may be considered for nodules in iodine-deficient areas or for small, benign lesions in younger patients. T4 treatment with TSH suppression, however, may be associated with significant adverse effects and

T4 therapy is best avoided in patients with thyroid nodules. Follow-up reaspiration of the nodule is left to the judgment of the clinical endocrinologist. However, in case of a more than 50% increase in nodule volume confirmed by US a repeat FNA is recommended.

1

Figure 1. Case 1. Thyroid cytology shows normal follicular cells and colloid. Diagnosis is benign or colloid nodule.

6 Thyroid International 1 2011

Case 2: Thyroid Cyst

A 64-year-old man reports left neck pain of one week duration. He denies trauma, fever, symptoms of hyperthyroidism, and has no history of prior thyroid disease.

On examination he appears euthyroid. A tender, 3-cm left thyroid mass is palpable; right thyroid is normal.

Serum TSH is 2.2 mIU/L and FT4 is 1.5 ug/dL. Thyroid

US shows a 3.0 × 3.5 × 4.0 cm predominantly cystic nodule with a tiny solid component (Figure 2). US-guided

FNA biopsy yielded 12 mL clear, yellow-colored fluid.

Cystic fluid was acellular but US-guided FNA smears showed benign cytology.

How common are thyroid cysts?

Studies using thyroid US show that approximately 25% of solitary nodules are cystic or have a cystic component.

3 Nodules may be purely cystic or mixed cystic and solid; pure or simple cysts, almost always benign, are very uncommon. Because cystic nodules are usually benign, the presence of a cyst is usually reassuring, although FNA biopsy is always necessary to rule out malignancy.

Management?

Asymptomatic, small, and benign cysts may be followed. While many remain stable in size, a few do enlarge and require treatment. The first step in management is simple evacuation of fluid. It is important to emphasize that after cystic drainage, fluid should be submitted to the laboratory for analysis. Most colloid cysts yield clear and yellow fluid; a clear, colorless fluid is likely of parathyroid origin and should be submitted for parathyroid hormone measurement. Hemorrhagic cystic fluid carries a higher risk of malignancy.

22,28

After complete drainage of the cyst, the solid area should be carefully sampled by FNA.

Cysts frequently recur after drainage with increasing size causing both neck discomfort and anxiety.

Therefore, recurrent or symptomatic cysts often end up with surgical excision. However, percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) is a nonsurgical alternative for treating benign thyroid cysts. This procedure is now available as an effective alternative to surgery and several Italian

Figure 2. Case 2. Thyroid ultrasound shows a cyst with some debris within the cyst cavity near the posterior wall.

Fine-needle aspriration was benign.

studies have reported a success rate of 50% to 90% after alcohol injection into cystic thyroid nodules.

29-34 The recurrence rate of cysts after PEI is less than 5%, being less common in lesions with cystic component of more than 75%. Frequently, a single injection results in complete disappearance or at least a significant reduction in the cyst size; seldom 2 or more injections may be necessary. PEI, when done by experienced personnel, appears to be safe and without either significant or lasting complications. It is a minimally invasive, nonsurgical procedure recommended for patients with biopsyproven benign but symptomatic thyroid cysts. PEI has also been tried on solid or toxic nodules but is currently is not recommended for these types of thyroid nodules.

35

Case 3: Suspicious Nodule

A 46-year-old woman, discovered to have a right thyroid mass by her gynecologist, is referred for a thyroid consultation. She has no prior history of thyroid disease or treatment and denies childhood radiation exposure.

She reports no neck pain or pressure. She is clinically euthyroid. Thyroid palpation confirms the presence of a

3 × 2 cm firm, solitary right thyroid nodule. Left thyroid feels normal. Serum TSH is 0.8 mIU/L. FNA biopsy smears show absent colloid, hypercellularity, and microfollicle formation. The final report is follicular neoplasm.

What is the risk of cancer in this thyroid nodule?

The estimated risk of malignancy in this nodule is around 10%.

21,25,36 Currently, there are no clear-cut morphologic criteria to distinguish benign from malignant follicular lesions. Repeat biopsy, a large, or a cutting-needle biopsy is not recommended because none of these procedures provides additional, useful information to assist in her care.

Are molecular markers useful?

Many molecular and cytohistochemical markers have been evaluated to separate benign from malignant cytologically suspicious tumors. These include BRAF,

PAX8, Galectin-3, HBME, and RET/PTC, 37-40 some of which are available commercially. However, the reported accuracy and predictive value of these tests are variable and at times discordant. FNA smears staining positive for galectin-3 are more likely malignant than those that do not.

38 With research in this area in progress and definite recommendations lacking, the guidelines state that “routine use of markers in clinical practice is not recommended and should be reserved for selected cases”.

1

Management of follicular neoplasm?

Conventional cytologic classification has 4 categories: nondiagnostic, benign, indeterminate, and malignant.

22,25 The 2010 guidelines use 5 classes, further subdividing the indeterminate cytology into follicular lesions (low risk) and suspicious results (high risk)

(Table 3).

All patients with indeterminate cytology need surgery but the extent of surgery remains controversial.

The guidelines suggest tailoring surgical excision based on FNA report.

When cytology shows a follicular lesion, initial surgery should be lobectomy plus isthmectomy, considering the low risk (10%) of malignancy. Conversely, total thyroidectomy is the appropriate initial approach for the patient with a suspicious aspirate suggestive of papillary thyroid carcinoma (60% cancer risk), when there is a history of prior neck irradiation, or when bilateral thyroid nodules are noted pre- or intraopertively. In most centers, intraoperative frozen section examination of tissue is considered of limited value in distinguishing benign from malignant follicular tumors.

21,25

The finding of follicular neoplasm on FNA is an accepted inherent limitation of thyroid cytologic analysis that leads to unnecessary, yet unavoidable, surgery.

7

8 Thyroid International 1 2011

Case 4: Multinodular goiter

A 76-year-old woman is referred with a multinodular goiter. She has a long history of goiter, reportedly increasing in size and symptoms in recent months. She complains of neck pressure, dyspnea, mild dysphagia, and poor sleep. She has noted recent increased heart rate with exertion. She also has a history of treated congestive heart failure, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and arthritis. Examination shows an elderly woman who is in no acute distress and appears euthyroid; there is no ophthalmopathy; Pemberton sign is positive; thyroid gland is diffusely enlarged, nodular, and firm, with estimated weight around 80 grams; cardiac examination shows a grade 2 systolic murmur; lungs are clear; and there is pitting edema of both shins and ankles. Laboratory tests include a serum TSH 0.4 mIU/L, FT4 1.8 ug/dL, T3

172 ng/dL, and thyroperoxidase negative. A radioactive iodine scan shows changes of a multinodular goiter with patchy uptake and hot and cold areas; 24-hour uptake is 14%. A chest X-ray was abnormal and a neck-chest computed tomography scan shows a large cervical goiter extending into the upper mediastinum (Figure 3).

Management Options: Surgery

Most of this patient’s symptoms are caused by the enlarged goiter without evidence of biochemical hyperthyroidism. In an elderly patient with an asymptomatic nontoxic goiter, observation without treatment is one acceptable option.

21 However, in this case the development of symptoms with a history of an enlarging goiter warrants special attention and treatment.

Conventional treatment would be surgery, either a total or a near-total thyroidectomy. Thyroidectomy is safe, promptly relieves compressive symptoms, and improves respiratory function. When performed at experienced centers, complications of thyroidectomy such as recurrent laryngeal nerve injury or hypoparathyroidism are very low. Postoperative hypothyroidism can be easily managed with T4 replacement. However, our elderly patient with multiple comorbid conditions is a high-risk surgical case and a nonsurgical alternative, if safe and effective, should be considered.

Figure 3. Case 4. Chest X-ray (A) shows a right upper

mediastinal mass. Neck computed tomography scan without contrast (B) shows this mass to be a diffusely enlarged nodular goiter extending into the upper chest. Note marked tracheal deviation to left.

Radioiodine

Numerous reports of radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment in patients with nontoxic nodular goiters have shown improved symptoms as well as pulmonary function due to substantial reduction of goiter volume.

41-45 RAI is most effective in small- to moderate-size goiters and is an attractive alternative to thyroidectomy in patients previously treated with surgery, for those who decline surgery, or patients with conditions that increase risk for surgical treatment. RAI often results in a significant reduction of thyroid volume in one year, with approximately 60% volume decrease within 5 years.

1 The degree of response can be quite variable, and 20% may not respond at all. It seems that very large goiters

(> 100 mL) do not respond as well as medium-sized goiters. Early adverse effects of RAI include acute increase in goiter size, radiation thyroiditis, or hyperthyroidism.

The only late complication is hypothyroidism, reported in 20% to 50% of patients.

1 It is unclear if RAI results in radiation-induced thyroid or extra-thyroid cancer.

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules 9

The use of RAI treatment may be limited because RAI uptake is often low or low-normal in patients with multinodular goiter with the gland uptake often being patchy and irregular in the large goiter. These features render

RAI therapy less than optimally effective. Some investigators have shown that pretreatment with recombinant human TSH (rhTSH) can increase uptake and enhance goiter volume reduction by as much as 30% to 50% more than when RAI is used alone.

46-49 The optimal dose of rhTSH seems to be 0.1 mg per patient. At present, this use is considered off-label and not approved by the Food and

Drug Administration. However, it is now well-documented that rhTSH leads to an increased uptake, resulting in enhanced delivery of RAI to the thyroid, and promoting goiter size reduction. So far, the only adverse effect has been a 5-fold increase risk of hypothyroidism, which is noted in up to 65% of treated patients.

48 It is expected that in the near future rhTSH may be approved for use with RAI to treat patients with nontoxic nodular goiters.

Thyroxine (T4)

T4 suppressive therapy is not recommended for large nontoxic nodular goiters. It seems to be ineffective in significant goiter reduction in most patients as well as causing important adverse effects. Adverse effects caused by TSH suppression include bone loss and atrial fibrillation.

13,27

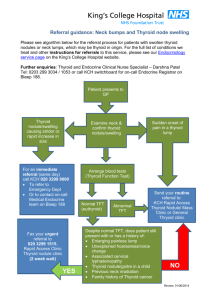

Summary

Thyroid nodule evaluation begins with a careful history and physical examination, followed by an US exam and

TSH+FT4 measurement (Figure 4).

With a low serum TSH additional tests are done to rule out hyperthyroidism

(right side of algorithm). When TSH is normal and US shows a suspicious/indeterminate nodule > 1.0 cm, the next step is US-guided FNA (left side). Most nodules yield benign aspirates and are followed. When cytology is either suspicious or malignant, surgery is recommended.

Conclusion

Thyroid nodules are a common clinical problem, and their evaluation and management is continually changing. The current revised guidelines by the American

Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazone

Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association provide updated and evidence-based recommendations by expert thyroidologists. This document reflects a state-of-the-art consensus in 2010 which will need revision in the future.

Figure 4. Algorithm for the diagnosis and management of palpable thyroid nodules

History

Physical Examination

TSH + Free thyroxine

CaIcitonin?

Thyroid US with focus on risk stratification or malignancy

Nodule diameter

<1 cm without suspicious history or suspicious US findings

Nodule diameter

>1 cm or <1 cm with suspicious history or suspicious US findings

Normal TSH

Suspicion for malignancy by clinical or US criteria

Low TSH or MNG in iodine-deficient region

Normofunctioning or cold on thyroid scintigraphy

Follow-up No Yes

FNA biopsy

Benign Follicular lesion

Suspcious

Positive for malignant cells

FNA, fine-needle aspiration; MNG, multinodular goiter; TSH, thyrotropin; US, ultrasonography.

Surgery

10 Thyroid International 1 2011

References

1. Gharib H, Papini E, Paschke R, et al. American Association of

Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association Medical Guidelines for

Clinical Pratice for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid

Nodules. Endocr Pract 2010;16:1-43.

2. Vander JB, Gaston EA, Dawber TR. The significance of nontoxic thyroid nodules: final report of a 15-year study of the incidence of thyroid malignancy. Ann Intern Med

1968;69:537-40.

3. Rojeski MT, Gharib H. Nodular thyroid disease: evaluation and management. N Engl J Med 1985;313:428-36.

4. Ezzat S, Sarti DA, Cain DR, et al. Thyroid incidentalomas: prevalence by palpation and ultrasonography. Arch Intern

Med 1994;154:1838-40.

5. Mortensen JD, Woolner LB, Bennett WA. Gross and microscopic findings in clinically normal thyroid glands. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 1955;15:1270-80.

6. Tan GH, Gharib H, Reading CC. Solitary thyroid nodule: comparison between palpation and ultrasonography. Arch

Intern Med 1995;155:2418-23.

7. Tan GH, Gharib H. Thyroid incidentalomas: management approaches to nonpalpable nodules discovered incidentally on thyroid imaging. Ann Intern Med 1997;126:226-31.

8. Burguera B, Gharib H. Thyroid incidentalomas: prevalence, diagnosis, significance, and management.

Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2000;29:187-203.

9. Boelaert K, et al. Serum thyrotropin concentration as a novel predictor of malignancy in thyroid nodules investigated by FNA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:4295-301.

10. Haymart MR, Repplinger DJ, Leverson GE et al. Higher serum TSH in thyroid nodule patients is associated with greater risk of differentiated thyroid cancer and advanced tumor stage. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 2008;93:809-14.

11. Gharib H, Papini E. Thyroid nodules: Clinical importance, assessment, and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North

Am 2007:707-35.

12. Mandel SJ. Diagnostic use of ultrasonography in patients with nodular thyroid disease. Endocr Pract 2004;10:246-52.

13. Hegedus L. Clinical practice: the thyroid nodule. N Engl J

Med 2004;351:1764-71.

14. Frates MC, Benson CB, Charboneau JW, et al; Society of

Radiologists in Ultrasound. Management of thyroid nodules detected at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference statement. Radiology 2005;237:794-800.

15. Papini E, Guglielmi R, Bianchini A, et al. Risk of malignancy in nonpalpable thyroid nodules: predictive value of ultrasound and color-Doppler features. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 2002;87:1941-6.

16. Carmeci C, Jeffrey RB, McDougall IR, et al. Ultrasoundguided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid masses.

Thyroid 1998;8:283-9.

17. Cochand-Priollet B, Guillausseau PJ, Chagnon S, et al. The diagnostic value of fine-needle aspiration biopsy under ultrasonography in nonfunctional thyroid nodules: a prospective study comparing cytologic and histologic findings. Am Med 1994;97:152-7. Erratum in: Am J Med

1994;97:311.

18. Pacini F, Fontanelli M, Fugazzola L, et al. Routine measurement of serum calcitonin in nodular thyroid diseases allows the preoperative diagnosis of unsuspected sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab 1994;78:826-9.

19. Niccoli P, Wion-Barbot N, Caron P, et al, The French

Medullary Study Group. Interest of routine measurement of serum calcitonin: study in a large series of thyroidectomized patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:338-41.

20. Elisei R, Bottici V, Luchetti F, et al. Impact of routine measurement of serum calcitonin on the diagnosis and outcome of medullary thyroid cancer: experience in

10,864 patients with nodular thyroid disorders. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:163-8.

21. Gharib H. Changing concepts in the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules. Endocrinol Metab Clin North

Am 1997;26:777-800.

22. Gharib H. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules: advantages, limitations, and effect. Mayo Clin Proc

1994;69:44-9.

23. Goellner JR, Gharib H, Grant CS, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of the thyroid, 1980 to 1986. Acta Cytol

1987;31:587-90.

24. Gharib H, Goellner JR. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules. Endocr Pract 1995;1:410-7.

25. Gharib H, Goellner JR. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid: an appraisal. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:282-9.

26. AACE/AME Task Force on Thyroid Nodules. American

Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and Associazione

Medici Endocrinologi medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules.

Endocr Pract 2006;12:63-102.

27. Gharib H, Mazzaferri EL. Thyroxine suppressive therapy in patients with nodular thyroid disease. Ann Intern Med

1998;128:386-94.

28. Castro MR, Gharib H. Continuing controversies in the management of thyroid nodules. Ann Intern Med

2005;142:926-31.

29. Lippi F, Manetti L, Rago T. Percutaneous ultrasoundguided ethanol injection for treatment of autonomous thyroid nodules: results of a multicentric study [abstract].

J Endocrinol Invest 1994;17 Suppl 2:71.

30. Zingrillo M, Torlontano M, Chiarella R, et al. Percutaneous ethanol injection may be a definitive treatment for symptomatic thyroid cystic nodules not treatable by surgery: five-year follow-up study. Thyroid 1999;9:763-7.

31. Kim JH, Lee HK, Lee JH, et al. Efficacy of sonographically guided percutaneous ethanol injection for treatment of thyroid cysts versus solid thyroid nodules. AJR Am J

Roentgenol 2003;180:1723-6.

32. Valcavi R, Frasoldati A. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous ethanol injection therapy in thyroid cystic nodules. Endocr

Pract 2004;10:269-75.

33. Guglielmi R, Pacella CM, Bianchini A, et al. Percutaneous ethanol injection treatment in benign thyroid lesions: role and efficacy. Thyroid 2004;14:125-31.

34. Bennedbaek FN, Hegedus L. Treatment of recurrent thyroid cysts with ethanol: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:5773-7.

35. Papini E, Panunzi C, Pacella CM, et al. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided ethanol injection: a new treatment of toxic autonomously functioning thyroid nodules? J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 1993;76:411-6.

36. Gharib H, Goellner JR, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid: the problem of suspicious cytologic findings. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:25-8.

37. Segev DL, Clark DP, Zieger MA, et al. Beyond the suspicious thyroid fine needle aspirate: a review. Acta Cytol

2003;47:709-22.

38. Bartolazzi A, Gasbarri A, Papotti M, et al, Thyroid Cancer

Study Group. Application of an immunodiagnostic method for improving preoperative diagnosis of nodular thyroid lesions. Lancet 2001;357:1644-50.

39. Castro MR, Gharib H. Thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsy: progress, practice, and pitfalls. Endocr Pract

2003;9:128-36.

40. Miettinen M, Karkkainen P. Differential reactivity of

HBME-1 and CD15 antibodies in benign and malignant thyroid tumors: preferential reactivity with malignant tumours. Virchows Arch 1996;429:213-9.

41. Huysmans DA, Hermus AR, Corstens FH, et al. Large, compressive goiters treated with radioiodine. Ann Intern

Med 1994;121:757-62.

42. Hegedus L, Hansen BM, Knudsen N, et al. Reduction of size of thyroid with radioactive iodine in multinodular non-toxic goitre. BMJ 1988;297:661-2.

43. Nygaard B, Hegedus L, Gervil M, et al. Radioiodine treatment of multinodular non-toxic goitre. BMJ 1993;307:828-32.

44. de Klerk J, van Isselt JW, van Dijk A, et al. Iodine-131 therapy in sporadic nontoxic goiter. J Nucl Med

1997;38:372-6.

45. Silva MN, Rubio IG, Knobel M, et al. Treatment of multinodular goiters in elderly patients with therapeutic doses of radioiodine preceded by stimulation with human recombinant TSH. Endocr J 2000;47 Suppl;144.

46. Duick DS, Baskin HJ. Utility of recombinant human thyrotropin for augmentation of radioiodine uptake and treatment of nontoxic and toxic multinodular goiters.

Endocr Pract 2003;9:204-9.

47. Duick DS, Baskin HJ. Significance of radioiodine uptake at 72 hours versus 24 hours after pretreatment with recombinant human thyrotropin for enhancement of radioiodine therapy in patients with symptomatic nontoxic or toxic multinodular goiter. Endocr Pract

2004;10:253-60.

48. Bonnema SJ, Hegedus L. A 30-year perspective on radioiodine therapy of benign nontoxic multinodular goiter.

Curr Opin Diabetes Obes 2009;16:379-84. 49. Nielsen VE,

Bonnema SJ, Hegedus L. Transient goiter enlargement

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules 11 after administration of 0.3 mg of recombinant human thyrotropin in patients with benign nontoxic nodular goiter: a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:1317-22.

12 Thyroid International 1 2011

Former Editions of Thyroid International

No 5-2010 Highlights of the 14 th International Thyroid

Congress 11 th –16 th September 2010, Palais des Congrès, Paris (Clara V Alvarez, Stephen W

Spaulding, Peter PA Smyth)

No 4-2010 The interaction between growth hormone and the thyroid axis (Lucy Ann Behan, Amar Agha)

No 3-2010 Transient Hypothyroxinemia of Prematurity: Current

State of Knowledge (Nevena Simic, Joanne Rovet)

No 2-2010 3-Iodothyronamine (T1AM): A new thyroid

hormone? (Barbara D Hettinger, Kathryn G Schuff,

Thomas S Scanlan)

No 1-2010 Report on the 34 th Annual Meeting of the

European Thyroid Association

(Clara V Alvarez and Peter PA Smyth)

No 5-2009 Factors Affecting Thyroid Hormone Gastrointestinal

Absorption (Kenneth D. Burman, M.D.)

No 4-2009 Iodine Deficiency Disorders: Silent Pandemic

(Fereidoun Azizi)

No 3-2009 American Thyroid Association:

Highlights of the 79th Annual Meeting

(Stephen W Spaulding, P.P.A. Smyth)

No 2-2009 Epidemiology of Thyroid Dysfunction –

Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism

(M.P.J. Vanderpump)

No 1-2009 Report on the 33rd Annual Meeting of the European Thyroid Association

(L.H. Duntas, P.P.A. Smyth)

No 4-2008 Thyroid autoimmunity and female infertility

(Kris Poppe, Daniel Glinoer, Brigitte Velkeniers)

No 3-2008 New reference range for TSH?

(Georg Brabant)

No 2-2008 American Thyroid Association: Highlights of the

78th Annual Meeting (Stephen W Spaulding, Peter

PA Smyth)

No 1-2008 Report of the 32th Annual Meeting of the European

Thyroid Association (GJ Kahaly, P.P.A. Smyth)

No 4-2007 The Thyroid and Twins (Pia Skov Hansen, Thomas

Heiberg Brix, Laszlo Hegedüs)

No 3-2007 Clinical Aspects of Thyroid Disorders in the

Elderly (Valentin Fadeyev)

No 2-2007 Report of the 31th Annual Meeting of the European Thyroid Association

(John H Lazarus, Peter PA Smyth)

No 1-2007 The story of the ThyroMobil (F. Delange,

C.J. Eastman, U. Hostalek, S. Butz, P.P.A. Smyth)

No 3-2006 Thyroid Peroxidase – Enzyme and Antigen

(Barbara Czarnocka)

No 2-2006 Genetics of benign and malignant thyroid tumours

(Dagmar Führer)

No 1-2006 Highlights of the 13th ITC

(Sheue-yann Cheng, Peter PA Smyth)

No 4-2005 Thyroid Eye Disease:

Current Concepts and the EUGOGO Perspective

(Gerasimos E Krassas, Wilmar M Wiersinga)

No 3-2005 Clinical Expression of Mutations in the TSH

Receptor: TSH-R Disorders

(Davide Calebiro, Luca Persani, Paolo Beck-Peccoz)

No 2-2005 Transient Hypothyroxinaemia and

Preterm Infant Brain Development

(Robert Hume, Fiona LR Williams, Theo J Visser)

No 1-2005 The Spectrum of Autoimmunity in Thyroid Disease

(Anthony P. Weetman)

No 5-2004 Postpartum Thyroiditis: An Update

(Kuvera E. Premawardhana, John H. Lazarus)

No 4-2004 Report of the 29th Annual Meeting of the

European Thyroid Association (G. Hennemann)

No 3-2004 Autoimmune Thyroiditis And Pregnancy

(Alex F. Muller, Arie Berghout)

No 2-2004 Report of the 75th Annual Meeting of the

American Thyroid Association (G. Hennemann)

No 1-2004 Thyroid and Lipids: a Reappraisal

(Leonidas H. Duntas)

No 5-2003 Use of Recombinant TSH in Thyroid Disease:

An Evidence-Based Review (Sara Tolaney M.D.,

Paul W. Ladenson M.D.)

No 4-2003 New Insights for Using Serum Thyroglobulin

(Tg) Measurement for Managing Patients with

Differentiated Thyroid Carcinomas (C.A. Spencer)

No 3-2003 The Significance of Thyroid Antibody Measurement in Clinical Practice (A. Pinchera, M. Marinò, E. Fiore)

No 2-2003 Etiology, diagnosis and treatment of Graves’ disease

(A.P. Weetman)

No 1-2003 Report of the 74th Annual Meeting of the

American Thyroid Association (G. Hennemann)

No 6-2002 Report of the 28th Annual Meeting of the

European Thyroid Association (G. Hennemann)

No 5-20 02 Iodine Deficiency in Europe anno 2002

(François M. Delange, MD, PhD)

No 4-20 02 Thyroid Imaging in Nuclear Medicine

(Dik J. Kwekkeboom, Eric P. Krenning)

No 3-20 02 Congenital Hypothyroidism (Delbert A. Fisher)

No 2-20 02 The Use of Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy (FNAB) in

Thyroid Disease (Antonino Belfiore)

No 1-20 02 Report of the 73rd Annual Meeting of the

American Thyroid Association (G. Hennemann)

No 6-2001 Report of the 27th Annual Meeting of the

European Thyroid Association (G. Hennemann)

No 5-2001 Subclinical Hyperthyroidism

(E.N. Pearce, L.E. Braverman)

No 4-2001 Thyroid hormone treatment – how and when?

(A.D. Toft)

Thyroid International is also published on the website ThyroLink: www.thyrolink.com (Literature)

Taking the offensive against hypothyroidism. With Euthyrox.

• multiple dosage strengths for precise dose titration

• galenic formulation with reliable unit conformity

• first levothyroxine preparation with a European and FDA approval

Other registered tradenames: Eutirox, Supratirox, Lévothyrox

Euthyrox

®

Offensive against hypothyroidism.

Active substance: Levothyroxine sodium. Prescription only medicine. Composition: Each tablet (round with cross score) of Euthyrox 25/50/75/88/100/112/125/137/150/175/200 µg contains 25/50/75/88/100/112/125/137/150/175/200 µg of levothyro-