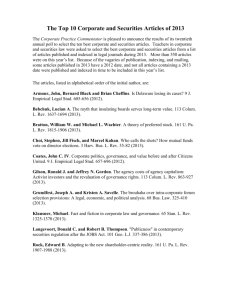

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Balkanization

advertisement