Divided Government and Party Responsiveness in the American

advertisement

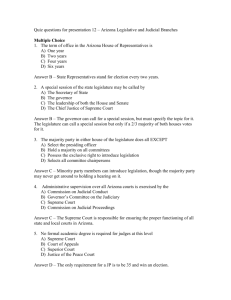

Divided Government and Party Responsiveness in the American States David W. Prince University of Kentucky Department of Political Science dwprin0@pop.uky.edu Prepared for presentation at the 2000 Southern Political Science Association annual meeting, Atlanta, Georgia November 8-11, 2000 Divided government has been the subject of much research. The majority of this research has focused on the Congress with less attention paid to the states. Most prominent among the exceptions is the work of Fiorina (1994), in which he examines the impact of professionalism on divided government in the states. The states are becoming more important in an era of policy devolution. Given that more decisions are being shifted back to the states, an examination of the policy making process at the state level becomes more pertinent. Research on divided government has focused on the causes (Fiorina 1994; Jacobson 1990; Petrocik 1991; Petrocik and Doherty 1996; Sigelman, Wahlbech, and Buell 1997; Wattenberg 1991) and consequences (Alt and Lowrey 1994; Cox and McCubbins 1991; Franklin and Hirczy de Mino 1998; Gilmour 1995; Jones 1994; Kelly 1993a; Kernell 1991; Lohmann and O’Holloran 1994). This research focus on the later question of the consequences of divided government. If divided government does not impact policy outcomes, then the causes are of little interest. However, if divided government impacts policy then the question of why divided government occurs is an important research question. If divided government impacts policy and we determine why divided government occurs, then we can offer recommendations to make divided government more or less likely to occur and gain greater insight into legislative outputs. The traditional view of parties is that they are more likely to enact legislation when they have unified control of the government. Divided government creates obstacles to lawmakers thus making legislation more difficult to enact. Edwards, Barrett and Peake (1997) found that important bills are more likely to fail during periods of divided government. Coleman (1999) analyzed party responsiveness under unified and divided 1 government and concluded that unified government is significally more productive than divided government. Mayhew (1991) challenged the conventional view of the cohesiveness of parties under unified government. He found that legislation was as likely to be enacted during periods of unified government as divided government. Other research has supported Mayhew’s argument (Jones 1994, 1997). Jones found that the Congress and the president were able to enact significant legislation under divided government. Quirk and Nesmith (1995) argue that gridlock is most likely when the parties are debating highly ideological issues and there has been no significant shift in public opinion and political pressure. Quirk and Nesmith (1994) suggest that circumstantial factors such as the budget deficit, issue complexity, and an uninformed public have a greater impact on gridlock than divided classes of significance. The top two categories are “landmark” and “major” legislation. Enactment of major legislation does not appear to vary significally between divided and unified government, but the enactment of landmark legislation differs from about two to three statutes per congressional term. This paper will examine the question of whether parties matter at the state level. I hypothesize, consistent with Mayhew, that the enactment of legislation is as likely to occur under divided government as unified government. This research will allow us to generalize beyond the single case of the national government. The states exhibit a variety of characteristics of political ideology, party identification, political culture, institutional structure and so forth. Expanding our research beyond the national level will allow us to begin the process of developing a unified theory of divided government. Additionally, this research will provide further insight into the question of party decline. It is reasonable to assume that divided government would be less significant in a weak party 2 system. An insignificant relationship between legislative enactments and divided government provides additional evidence that parties are on the decline in the United States. The primary research hypothesis for this study is divided government does not adversely effect the passage of legislation in the states. The hypothesis is consistent with David Mayhew’s (1991) findings at the national level. The analysis of this paper will be conducted on two levels. First, an empirical analysis will test the importance of divided government in the passage of legislation. The second, part of the analysis, conducted in future research, will be a content analysis of various newspapers in order to supplement the empirical analysis. The qualitative analysis will allow us to identify the important issues confronting the legislature and gain some insight into the effect of institutional structure on legislative success. Dependent Variable The dependent variable for this study is the percent of bills introduced by the legislature that pass and become law. The percentage of bills enacted serves several purposes. First, it allows us to obtain a standardized measure across legislatures. The states have varying agendas with some states facing a wider multitude of issues. For example, the state legislature in California is likely to have more issues before it than the Wyoming legislature, therefore, the use of the percent of bills enacted will allow us to account for the scope of the agenda under consideration. Resolutions are excluded from the analysis because they tend to be about inconsequential or unimportant issues. Mayhew (1991) has recognized the importance of only examining significant legislation; therefore, the inclusion of resolutions in the model would bias our findings toward the 3 research hypothesis. Resolutions are often procedural motions passed by unanimous consent, and therefore, party influences would likely be masked. The dependent variable included in this study makes it difficult, in many instances, to predict the direction of the relationship between the explanatory variables and the dependent variable. The anticipated direction of the relationship is clearer when examining the raw number of enacted bills. A legislature which is more active may have a lower percentage of bills enacted simply because they introduced a larger number of bills. Explanatory Variables Divided Government Divided government is the primary explanatory variable in this study. Divided government occurs when opposing parties occupy different components of the government. If the governor, the state house and the state senate are controlled by the same party, divided government is coded as 0 indicating that there is unified government. If different parties control two of the three components, the variable is coded as 1 indicating divided government. Governor’s Party The first control variable included in the model is the party of the governor. The variable is coded as 1 if the governor is a Democrat and as a 0 if the governor is a Republican. The party that controls the governorship should affect legislation regardless of the party that controls the legislature. The governor often takes the lead in setting the agenda for the state. Republicans and Democrats have different legislative priorities and 4 different philosophies of government. A Republican governor is expected to be less active than a Democrat and will therefore propose less legislation. The proposal of less legislation does not necessarily indicate there will be fewer enactments as a percent of proposals. The Republican agenda may be more focused than the Democratic agenda; therefore, while the actual number of enactments may be less as a percent of proposals, they may be higher under a Republican administration. Additionally, to help account for the relationship between the affects of divided government and the governor’s party an interaction variable is included in the model. Legislative Strength The legislative strength of the parties is expected to impact legislative success. One of the tasks of the party leaders is to prevent defection by their party members on legislative votes. The thinner the legislative majority, the greater the difficulty confronting the party leadership in enacting its agenda. If a party has more seats in the legislature it is easier to enact their agenda because party defectors do not have as great of an impact as when the party holds a sizable legislative advantage. The relationship between legislative success and number of seats, however, is not always linear. If a party has 95 percent of the seats then the battle becomes within the party instead of between the parties. Interparty fighting may have the same adverse affect on the passage of legislation as intraparty disagreements. Interaction terms between the Democratic majority in both houses and divided government will be included in the model to account for the impact of the size of the legislative majority on legislative success. 5 Two interaction variables will be included in the analysis. The interaction variable allows us to distinguish between various types of divided government. Divided government can take the form of two types. First, divided government with a divided legislature is likely to behave differently than divided government where one party controls the executive and the opposing party controls the legislative branch. In a unified legislature where the governor has weak veto power the legislature may operate in much the same fashion as it would under unified control. However, if there is a divided legislature the parties have to rely on the opposing party to pass legislation. The first variable will be calculated for the state house as follows: (Percent of Seats Held by Majority Party)(Dummy for Senate Control), where Same Party Control in senate = 1 Divided Part Control in Senate = 0 If the same party controls both houses then the interaction variable indicates the percent of seats held by the majority party in the house. On the other hand, if the opposing party controls the state senate, then the interaction variable will be equal to 0. In the same manner that the interaction variable is calculated for the house, an interaction variable is calculated for the senate. The inclusion of the interaction variables will allow a determination if divided legislative control has a negative impact on legislative enactments. Additionally, the interaction terms will lend evidence to address the question of whether the size of the legislative majority matters. It is expected that the greater the 6 legislative majority, the easier the task of enacting legislation. However, the size of the legislative majority is not as important if the opposing party controls the other chamber. Professionalism The effects of professionalism are controlled in this study. Fiorina (1994) identifies professionalism as a possible correlate with divided government. Legislative professionalism is also expected to affect the passage of legislation. More professional legislatures take on a wide range and number of issues and, therefore, it is expected that the more professional a legislature, the less successful the parties in enacting legislation. Squire (1992) recognizes three measures of professionalism- length of session, compensation and staff. Legislatures that are more professional are higher paid, meet for more days, and have a larger number of staff. The three indicators of professionalism are included in the model. Compensation is the salary the member makes for each year and the per diems received. The length of session is the number of days the legislature met during that session. If the state house and the state senate met for a different number of days an average of the two houses is included in the model. Session length may have a two-fold impact on enactments. First, the longer a legislature meets the greater the opportunity for members to consider legislation and to discuss a wider range of bills. Conversely, shorter sessions may increase the urgency to consider legislation quickly, and therefore legislators may be less apt to introduce non-significant legislation that takes valuable time and has little chance of passing. The final indicator of professionalism included in the model is staff. There are three categories of staff- personal staff, district staff, and shared staff. Since theoretically, 7 personal and district staff are more important than shared staff, they are weighed more. For each type of staff a score was calculated equaling zero if none were present, one half if part-time staff were present and one if full time staff were present. Each state was given a score based upon whether each of the three categories were full-time or part-time. Shared staff were weighed half of what personal and district staff were weighed. This resulted in a scoring ranging from zero, indicating no staff, to 2.5 designating full-time staff in each of the three categories. A state that had part-time staff in each of the categories would receive a score of 1.25. Election Year Legislatures tend to be more active in sessions immediately following an election. This trend is likely to occur regardless of whether there is a shift in the partisan balance of the legislature. If the incumbent party wins reelection, then they are likely to claim they have a mandate from the voters and, therefore, become more active in the legislative arena. In the same vein, a new party also feels they have a mandate to change policy and will be eager to enact its agenda. On the other hand, election years may result in a more narrow legislative scope. Legislators may only consider bills that are the most critical and save non-critical legislation to after the election. The magnitude of the number of bills will likely be greater when party control changes, however, in either case it is expected that a legislature will be more active immediately following an election than prior to the election. It is unclear how increased activism after the election translates into change in the percentage of bills enacted. A variable is included in the analysis to indicate if it is an election year. Most states conduct governor and state legislative races in the same year. The election year 8 variable indicates if there is a governor’s election. It becomes more difficult to enact legislation in the year before an election. For example, it is easier to enact a tax increase immediately following an election than before an election; therefore, legislators will postpone a decision to raise taxes until after an election. The parties in a legislature often attempt to block legislation in an election year so the opposing party does not receive credit for passage, thus increasing electoral success. The variable is coded as a 1 if it is an election year and as 0 if it is not an election year. Fewer enactments are expected to occur in election years but as previously stated it is unclear how this translates into the percentage of bills passed. Veto Power The veto power of the governor is expected to affect the enactment of legislation. It is expected that less legislation will be enacted under divided government when the governor has the veto. Additionally, some governors have stronger veto powers than others. It is hypothesized that less legislation will be enacted when the governor has a line item veto. Additionally, a supermajority required to override a veto increases the power of the governor’s veto. A governor with a line item veto that requires a supermajority would be in a stronger position to influence the legislation that is passed. The greater the veto power of the governor, the more difficult it is for the legislature to pass bills under divided government. Even when the governor does not use the veto the threat of the veto still makes it more difficult to pass legislation. Three indicators of veto power are included in the model. The variables are coded as a 1 if there is a veto, line item veto and supermajority to override and as a 0 if not present. 9 Ideology It is expected that the more liberal a state the more active the legislature. However, it is difficult to determine how the impact of ideology given the limitations of dependent variable discussed earlier. The measure created by Berry, Ringquist, Fording, and Hanson (1998) is included in the model to count for the differences in ideology among the states. Berry, Ringquist, Fording, and Hanson (1998) created a dynamic measure of ideology. Their measurement is an improvement over the static measure of Erikson, Wright and McIver (1993). Their measurement is based on roll call voting scores of state congressional delegations, the outcomes of congressional elections, the partisan division of state legislatures, the party of the governor and other various assumptions. The measure of Berry et al, contrary to the belief of many scholars, reveals that ideology varies more from year to year than is recognized. In order to gain greater purchase on the effects of ideology, both the Berry et al. measure and the Erikson, Wright, and McIver (1993) will be included in the model. The two indicators measure different aspects of ideology. The Berry et al. measure captures short term variation in ideology, while the Erikson Wright and McIver (1993) measure is not sensitive to short term upheavals in the electorate. Party Identification The party identification of a state should play a role in legislation enacted in the states. I expect that Democratic states have a more active legislative agenda than Republican states. Erikson, Wright and McIver (1993) formulate a measurement of state party identification derived from an aggregation of CBS/NYT polls conducted from 1976 to 1988. The aggregation of data helps to overcome the problem of small sample sizes of 10 many states when single year data is used. Erikson, Wright, and McIver (1993) recognize the changing nature of party identification across time. While it would be preferable to have a dynamic measurement for each year considered in the study difficulties in obtaining adequate sample sizes makes formulating a dynamic measure extremely problematic. Additional work needs to be conducted to determine approaches that will allows us to establish a dynamic measure of partisanship, however, due to data considerations and a lack of a better measure, the index formulated by Erikson, Wright and McIver will be incorporated into the analysis. The measure indicates a mean score of party identification ranging from –100 indicating total Republican identification to 100 indication Democratic identification. These mean scores will be included in this analysis as an indicator of partisan strength. Political Culture Elazar (1966, 109) defines political culture as “ the particular pattern of orientation to political action in which each political system is embedded.” The political culture of a state appears to be one of the overriding factors in shaping political structure and the electoral behavior of a state. A measurement of political culture is included in the study to account for the differences in the political orientations of the states. Elazar (1966) identifies three political cultures in the American states – individualistic, moralistic, and traditionalistic1. A moralistic state is a commonwealth where government can play a positive role in the lives of citizens. In contrast, an individualistic state is a marketplace and a traditionalistic state sees government’ s role as maintaining the existing 1 For classification of individual states, see Elazar (1966). Elazar also further divides states into categories indicating leanings toward a specific culture. Additionally, Nardulli (1990) examines political subcultures of states, however due to the aggregate this study the three major categories of Elazar are efficient. 11 order. Moralistic states are more pro government, therefore, it is expected that more legislation will be enacted in moralistic states than in traditionalistic or individualist states. Conversely, traditional states see government’ s role as maintaining the status quo; therefore it is expected that the level of enactments will be lower in traditional states. Two variables of political culture are included in this study. First, a dummy variable indicating if the state is moralistic and second a dummy variable indicating if the state is traditionalistic. An important assumption is made that political culture is stable across time. There is little evidence that political cultures change greatly across time. Two separate variables are included due to the non-continuous nature of political culture. Methods This study will examine regular sessions of all state legislatures from 1978 to 1998 with the exception of Nebraska, which unicameral legislature renders it analytically distinct from the other states. Special sessions are excluded from the analysis. Special sessions often deal with very specific issues and, therefore, are not representative of the normal legislative pattern. The sample is chosen because a 20-year period provides an adequate range to determine the effects of divided government independent of contextual situations. Additionally, future research should expand the data set, thus allowing us to make inferences about divided government and party responsiveness in the individual states. An OLS model will be run with legislative enactments as a percent of total bills introduced as the dependent variable. Divided government is the primary explanatory variable with controls for governor’ s party, election year, veto, line item veto, 12 supermajority, compensation, length of session, staff, ideology, party identification, and political culture included in the model. Additionally, interaction variables between the party of the governor and divided government as well as between the legislative majority in each house and divided government will be included in the model. Future analysis will be supplemented by a content analysis of various newspapers to determine if the accounts are consistent with the findings of the empirical analysis. Autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity are a concern in cross sectional time series studies. Different methods have been developed to deal with the concerns of these types of studies. One common approach employed to deal with these problems is generalized least squares. However, Beck and Katz (1995) argue that generalized least squares results in inaccurate standard errors that cause overconfidence of the results of the study 2. Beck and Katz (1995) propose an alternative method for addressing the problems inherent in cross sectional time series studies. They argue that ordinary least squares is superior to the generalized least squares, and that a superior approach to dealing with cross sectional time series data is OLS with panel corrected standard errors.3 This paper will employ the approach set forth by Beck and Katz (1995). Ordinary least squares will be run with panel corrected standard errors. From this analysis, hopefully, some insight will be gained into the question of the impact of divided government. OLS estimators do not make efficient use of the data in the presence of autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity common in cross sectional time series data. The corrected standard errors provide more accurate estimates of the variability of the parameter estimates. Parks (1967) advocated the use of feasible generalized least squares 2 See Parks (1967) for an explanation of the generalized least squares method 3 See Beck and Katz (1995) for a detailed explanation on the calculation of panel-corrected standard errors. 13 to combat the problems inherent in cross sectional time series data. The Parks method involves two transformations. The first to eliminate the serial correlation of the errors and the second to eliminate the contemporaneous correlation of the errors. The Parks method is successful in correcting for heteroscedasticity, however, the solution is problematic as a solution for autocorrelation. The Parks (1967) method is only useful when the number of time periods is as large as the number cross sectional units or in most cases considerably larger than the number of time periods. This is rarely the case in political science research. For example, a study that examines all fifty states would have to look at what happens across at least fifty years. It is more common to have a situation in which we examine all the states across a five or ten year time period. This paper examines all the states across twenty years, and therefore, use of the Parks method is problematic. Given the limitations of the Parks method it is necessary to look for alternative approaches to dealing with the problems of cross sectional time series data. Beck and Katz (1995) propose the use of ordinary least squares with panel corrected standard errors. The correction takes into account the contemporaneous correlation of the errors. In order to test the performance of the corrected standard errors Beck and Katz perform a Monte Carlo analysis which shows that the panel corrected standard errors outperform the Parks estimates and were more accurate in the presence of panel heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. The authors conclude that the use of OLS coefficients with panel corrected standard errors do not result in less accurate estimates in comparison with standard OLS, however, in many cases provide much more accurate the standard errors generated by OLS. 14 Results The model supports the hypothesis that divided government does not significantly affect the passage of legislation in the state legislatures (see Table 1). This analysis extends the work of Mayhew (1991) to the state level and supports his national level findings. Divided government is found not to be significant, however, the sign of the coefficient indicates a lower percentage of enactments under unified government. This finding seems to be counterintuitive, however, divided government likely results in more closed rules in which the party has carefully crafted the legislation prior to it being sent to the floor since the minority party controls another component of the government. In a unified government scenario the details of legislation can be hammered out on the floor instead of within the committee. Additionally, open rules result in more amendments thereby increasing the number of bills being considered. In turn, with legislative details being worked out on the floor, you are more likely to see legislation being defeated due to the increased volume. This underlines the need for future research to find ways to get at the impact of divided government on significant legislation. [Table 1 About Here] The findings also revealed that more professional legislatures enact a lower percentage of legislation. Staff, competition and session length all result in lower passage rates.4 However, only staff is significant in the model at a .05 level.5 This finding seems reasonable, given the fact that staff are directly involved in the legislative process. If a 4 Staff and compensation are correlated at a .54 level. Staff and session length are correlated at a .21 level Compensation and session length are correlated at .37 level 15 legislature has a large staff, it can draw up more legislation since the workload can be delegated to members of the staff. The breath of issues considered by New York and California give the legislature more issues to considered and, therefore, more opportunity to vote against legislation. The third professionalism measure included in the model is session length. The length of session is not significant, but it has the same sign as the previous indicators of professionalism. The presence of a veto and a line item veto were both significant. The presence of a veto resulted in a lower level of bills being enacted. Additionally, the line item veto also served to curtail the enactment of legislation. A supermajority present to override a veto was not significant in the model, however, it exerted a positive influence on enactments. The party of the governor did not statistically effect the enactment of legislation. Additionally, the interaction variable between the party of the governor and divided government as well as interaction variables created for the house and senate were not significant. Election years were found to contain higher levels of legislative enactments. This finding may be the result in a more narrow legislative scope in election years. In election years legislators may only consider those bills that are the most critical and save non-critical legislation to after the election. The two ideology variables included in the model behaved in the same direction, however, the dynamic model created by Berry et al. had a significant effect6. The more conservative the state the more legislation enacted. The Berry measure captures short5 When each of the three indicators of professionalism are included in the model individually they are each significant with a negative sign. Removal of two indicators of professionalism results in the house interaction variable being significant with a positive slope coefficient. 6 The Berry, Ringquist, Fording, and Hanson (1998) and Erikson, Wright, and McIver (1993) ideology measures are correlated at a .71 level. Removal of the Berry measure from the model results in the EWM measure being significant. Both ideology measures are significant when included separately in the model, however, only the Berry measure is significant when both measures are included in the model at the same time. 16 term variation in ideology, while the measure of Erikson, Wright and McIver captures the portion of ideology that is abiding. This finding on the surface is not consistent with the conservative philosophy of less government, however, the measurement of the dependent variable discussed previously makes it difficult to determine the causal direction of the relationship. The finding reveals that legislators are subjected to short term swings in the ideology of the citizens. When the electorate is more conservative less legislation is enacted. Conversely, when the electorate is more liberal they demand more government action. The party identification of the state was not significant in the analysis. Moralist states were found significally more likely to enact legislation than traditionalist or individualist states. This finding is consistent with Elazar’s operationalization of political culture. Moralist states are more likely to favor government solutions to societal problems. This finding offers evidence that legislation is driven by the context of the situation in which it operates. Additionally, this provides evidence that legislators respond to the desires of the people. In moralist states citizens generally want government to perform a wider variety of functions and, therefore, respond to the desires of the people a more ambition legislative agenda is pursued. Discussion Mayhew (1991) has rejected the use of non-significant legislation in the evaluation of the impact of divided government. The task facing researchers at the state level is much more daunting. Roll call votes are generally not available at the state level in the way it is nationally. A possible approach to a determination of significant legislation within the states is a content analysis of various newspapers. At the end of a 17 legislative sessions newspapers often publish a summary of the work of the legislature indicating the significant bills that were considered during that session. An examination of several newspapers provides some evidence that the conclusion reached previously is likely to hold, even if significant legislation is considered. In Tennessee the major issue confronting the state legislature during the 1999 session was tax reform. The tax reform proposals dominated the legislature and the divided government present was unable to work out a compromise on the issue. However, beyond tax reform nearly every other piece of significant legislation was enacted into law. The spokeswoman for the governor was quoted as indicating “ The Governor feels the General Assembly did act on important issues.” (de la Cruz 1999). The legislature acted on a variety of issues including creating the Department of Labor and Workforce Development, reforms to the state health care plans, laws to protect the elderly from deceptive advertising, and education reforms. The examination of the Tennessee session supports the research of Quirk and Nesmith (1994), in which they argued that divided government has it greatest impact on the consideration of “ landmark” and “ major” legislation. Divided government definitely killed the “ major” issue of tax reform in Tennessee, however, other significant pieces of legislation were enacted despite the presence of divided government. An examination of the California general assembly provides an alternative examination of the impact of divided government on the passage of legislation. Democrats in California were excited about their legislative prospects when Gray Davis became governor and they no longer had to deal with Pete Wilson. Democrats riding the wave of excitement from their electoral victory that unified government in California were expecting to enact legislation that had been bottled up by the governor for years. 18 However, despite their optimism the legislative session was less than rewarding with only a small portion of the Democratic agenda becoming law. The Democrats found it was just as difficult to enact legislation under divided government. The cases of Tennessee and California offer some evidence that divided government does not necessarily indicate legislative success. Future research needs to expand on the analysis of Tennessee and California to include a sample that is representative both across states as well as across time. A detailed content analysis on various newspapers will enable us to create a data set of significant enactments that can be examined empirically and systematically. Conclusions The model set forth in this paper behaved in the expected manner. Divided government was not significant in effecting the passage of legislation. Constituent based factors seemed to exert a great deal of influence in determining legislative outcomes. States with conservative patterns of identification were less likely to pass a large proportion of legislation than more liberal states. Legislators appear to reflect the views of the citizens of the state. These changes are often short term, therefore, swings in legislative agendas can vary greater from one session to the next. The research conducted in this study also provides evidence that parties are on the decline and that they are not necessarily the key actor in determining the legislative destiny of the state. Legislators are not responsive only to the party but have a much broader constituency to which they react. As discussed previously future research needs to concentrate on approaches to determining significant legislation within the states. The content analysis of newspaper is 19 a possible approach to address the concerns of Mayhew. This expanded analysis will, hopefully, alleviate some of the problems associated with the inclusion of all legislation that was part of this analysis. Additionally, an expansion of this current study to include more sessions will allow us to make determination of the impact of divided government in the various states. 20 Table 1 Percent of Enactments 1978-1998 Divided Government Governor’s Party (Divided Govt.) (Governor Party) Interaction Election Year Compensation Staff Length of Session Veto Line Item Veto Supermajority Ideology (Berry et.all) Ideology (EWM) Party Identification House Interaction Senate Interaction Moralist Traditionalist Constant N=720 Ordinary Least Squares Unstandardized Coefficients -1.660607 Panel-Corrected Standard Errors Significance 2.202637 0.451 -.8414309 2.44855 0.731 2.170447 3.117007 0.486 3.258851 -.0001123 -.1806397 -.0043106 1.341832 .0000595 .0603747 .0096927 0.015 0.059 0.003 0.657 -9.288694 -4.372938 2.488706 -.2964274 3.99464 1.691364 1.675352 .0534219 0.020 0.010 0.137 0.000 -.1257864 .0664819 .1192046 .0915591 0.291 0.468 .1467448 .0920467 0.111 -.1151734 .0924674 0.213 10.1137 1.160425 53.95805 1.610625 2.168445 6.300533 0.000 0.593 0.000 21 References Alt, James E., and Robert Lowry. 1994 “ Divided Government Fiscal Institutions and Budget Deficits: Evidence from the States.” American Political Science Review 88 (December): 811-828. Beck, Nathaniel.; Jonathan N. Katz. 1995. “ What to do (and not to do) With Time-Series Cross-Section Data.” American Political Science Review. (September ) 634-647. Berry, William D.; Evan J. Ringquist; Richard C. Fording; and Russell L. Hanson. 1998. “ Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the American States, 19601993. Journal of Politics. 42 (January): 327-348. Binder, Sarah A. 1999. “ The Dynamics of Legislative Gridlock, 1947-1996.” American Political Science Review 93 (September): 519-33. Coleman, John J. 1999. “ Unified Government, Divided Government and Party Responsiveness.” American Political Science Review 93 (December) pp821-835. Cox, Gary W. and Matthew D. McCubbins. 1991. “ Divided Control of Fiscal Policy.” In the Politics of Divided Government, ed. Gary W. Cox and Samuel Kernell. Boulder: Westview, pp 155-75. Del la Cruz, Bonna M. 1999. “ Lawmakers passed a wealth of Legislation” The Tennessean. Edwards, George C., III, Andrew Barrett, and Jeffrey Peake. 1997, “ The Legislative Impact of Divided Government.” American Journal of Political Science 41(April): 545-63. Elazar, Daniel 1966. American Federalism: A View from the States. New York: Crowell. Erikson, Robert S., Gerald C. Wright, and John P. McIver 1993. Statehouse Democracy. Cambridge University Press. Fiorina, Morris P. 1994. ” Divided Government in the American States: A Byproduct of Legislative Professionalism?” American Political Science Review 88 (June): 304316. Fiorina, Morris P. 1996. Divided Government. 2d ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Fletcher, Richard, and Jon R. Bond. 1996 “ The President in a More Partisan Legisaltive Arena.” Political Research Quarterly 49 (December): 729-48. 22 Franklin, Mark N., Wolfgang P. Hirczy de Mino. 1998. “ Separated Powers, Divided Government and Turnout in US Presidential Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (January): 316-326. Gilmour, John B. 1995. Strategic Disagreement: A Stalemate in American Politics, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Jacobson, Gary. 1990. The Electoral Origins of Divided Government, Boulder, CO: Westview. Jones, Charles O. 1994. The President in A Separated System, Washington DC: Brookings Institution. Jones, Charles O. 1997. “ Separating to Govern: The American Way.” In Presents Discounts: American Politics in the Very Late Twentieth Century, ed, Bryon E. Shafer. Chatham, NJ: Chatham House. Pp. 47-72. Kelly, Sean Q. 1993 “ Divided We Govern: A Reassessment.” Polity 25 (Spring): 475-84. Kernell, Samuel. 1991. “ Facing an Opposition Congress: The President’ s Strategic Circumstance.” In the Politics of Divided Government, ed. Gary W. Cox and Samuel Kernell. Boulder. CO Westview. Pp 87-112. Mayhew, David R. 1991. Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking and Investigations 1946-1990. New Heaven, CT: Yale University Press. Nardulli, Peter 1990.” Political Subcultures in the American States: An Empirical Examination of Elazar’ s Formulation. “ American Politics Quarterly 18: 287-315. Parks, Richard. 1967. “ Efficient Estimation of A System of Regression Equations When Disturbances Are Both Serially and Contemporaneously Correlated.” Journal of the American Statistical Association. 62:500-509. Petrocik, John R. 1991. “ Divided Government: Is it all in the Campaigns?” In the Politics of Divided Government, ed. Gary W. Cox and Samuel Kernell. Boulder. CO Westview. Pp 13-38. Petrocik, John R. and Joseph Doherty. 1996. “ The Road to Divided GovernemntChange, Uncertainity, and the Constitutioanl Order, ed Peter F. Galderisi with Roberta Q. Hertzberg and Peter McNamara Landham, MD:Rowman & Litchfield. Pp 85-107. Quirk, Paul J. and Bruce Nesmith. 1994. “ Explaining Deadlock Domestic Policymaking in the Bush Presidency.” In New Perspectives on American Politics, ed. Lawrence C. Dodd and Calvin Jillson. Washington DC: CQ Press. Pp 191-211. Quirk, Paul J. and Bruce Nesmith. 1995. “ Divided Government and Policy Making: Negotiating the Laws. “ In the Presidency and the Political System, 4th ed.,ed 23 Michael Nelson. Washington, DC: CQ Press. Pp. 531-54. Sigelman, Lee, Paul J. Walhbeck, and Emmett H. Buell, Jr. 1997 “ Votte Choice and the Preference for Divided Government: Lessons for 1992.” American Journal of Political Science 41 (July): 879-94. Squire, Peverill 1992. “ Legislative Professionalization an Membership Diversity in State Legislatures. “ Legislative Studies Quarterly 17:69-79. Wattenberg, Martin P. 1991. “ The Republican Presidential Advantage in the Age of Party Disunity.” In the Politics of Divided Government, ed Gary W. Cox and Samuel Kernell. Boulder, CO Westview. Pp. 39-55. 24