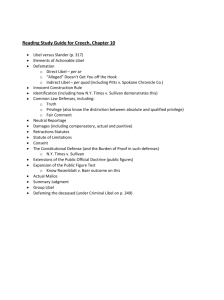

Libel Tourism: Protecting Authors and Preserving Comity

advertisement