competitive assessment - Greater Louisville Inc

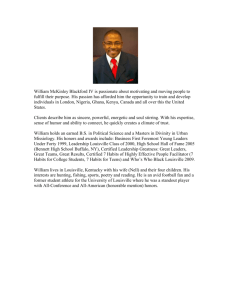

advertisement