Malignant Mesothelioma - American Cancer Society

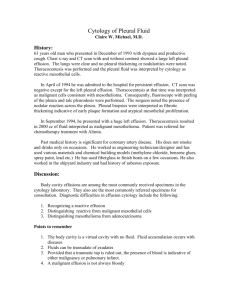

advertisement