Jazz in Britain: interviews with modern and contemporary jazz

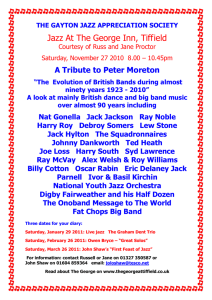

advertisement