?Have a question you'd like answered on our Ask the Experts page?

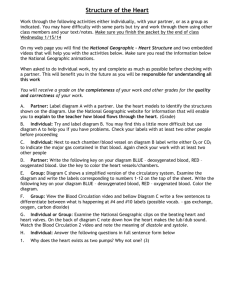

advertisement

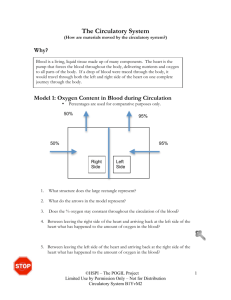

d r an ou t y ou ith ts! t Cu re w den a u sh st April/May 2007 Providing answers to science questions Send questions to Department Editor Marc Rosner; MARosner@aol.com Q What color is the blood in a person’s veins? I’ve heard it described as “blue,” but it looks to me to be dark red, as it appears when blood is drawn during a lab test. A Lori Glazik 8th Grade Science Teacher S.E. Gross Middle School Brookfield, Illinois Over two thousand years ago, Hippocrates, of the Ancient Greeks, took an interest in the color of blood as he philosophized that health is derived from the proper balance of pigmented humors. The human circulatory system drives approximately 25 trillion red blood cells through the body. Color is somewhat subjective—a product of the nature of incident light and absorbed and reflected wavelengths. The apparent color of blood is determined by hemoglobin molecules, which make up about one-third of the red cell’s content. The hemoglobin molecule binds four molecules of oxygen. During ? 58 normal conditions—that is, normal blood, under white light—fully oxygenated hemoglobin appears bright red. As the degree of oxygen saturation decreases, the internal molecular arrangement of the hemoglobin molecule changes in several directions, thereby causing it to reflect light of different wavelengths, and consequently changing its color. The color of deoxygenated venous blood is fairly accurately described as “dark maroon” or “reddish purple.” The fact that it is not, in fact, blue can be simply and decisively determined by looking at it as it comes from your vein to the collecting vacuum tube, or by observing the color of the blood in the collection bags at a blood donation center. Now, if you look at the veins of the back of your hand, they appear more nearly blue because the blue rays of the incident light scatter most readily in the numerous pigment layers below the skin surface; in general, the deeper the vein, the more blue it will look. If there are more than 5 g of reduced (deoxygenated) hemoglobin per 100 cc. of blood (about a third of the usual total amount of hemoglobin), the patient will have cyanosis, a bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes that is also caused by the interaction of light with skin pigments and dark-red deoxygenated blood. Diagrams of the circulation always show oxygenated blood as red and deoxygenated blood as blue, because it is much easier to grasp that difference than the one between bright and dark red. This type of agreed-upon depiction decision is called a convention. Likewise, we might use “red” to describe Mars or copper or a positive wire, even when an observer would say these are not truly red. The designation of deoxygenated blood as “blue” is more a convention based upon its relative hue than by our choice of a label we might apply to describe its color in isolation. It has been a useful teaching tool for centuries, and it might be difficult to change this convention. Perhaps “bright red” and “dark red” would be more accurate in discussion of blood in its oxygenated and deoxygenated states. William S. Rachlin, M.D., FACS, FACG Boston, Massachusetts Have a question you’d like answered on our Ask the Experts page? E-mail your question to Marc Rosner, department editor; MARosner@aol.com. In your e-mail, please include your name, school, and address. The Science Teacher