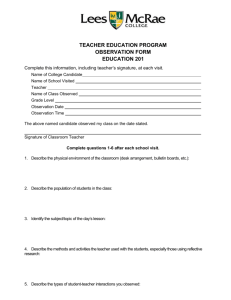

Living Room Candidate

advertisement

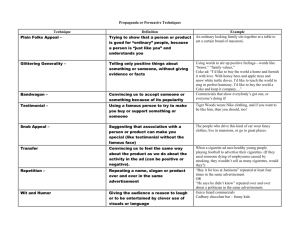

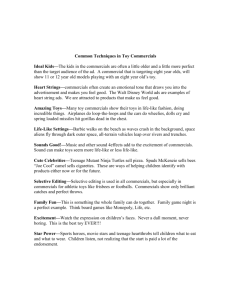

Living Room Candidate: [PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION CAMPAIGN COMMERCIALS] Part 1: Answer the general questions for the election, numbers 1 and 2. Most of this information is available on main page for the year, but the parties and results are available on the tabs to the right of the picture. Watch one commercial for each candidate for FIVE of the years, 1952, 1984 and 2012 are required; pick one on either side of 1984 the required year). Livingroomcandidate.org 1. The year, the candidates with their party affiliation 2. Winner of the election and the results a. (you can do both of these in a sentence—the information is available on the tabs—include the Electoral College vote) 3. Candidate #1 Commercial tactic/techniques of persuasion, give specific examples from the commercial to support the selected technique (should be a couple of sentences per commercial). 4. Candidate #2 Commercial tactic/techniques of persuasion (complete the same activity and assignment) Part 2: When you are done watching ALL of your commercials: Write a paragraph about how the “marketing” of presidential candidates in commercials has changed. Cite specific examples from your work in part one. TECHNIQUES YOU NEED TO KNOW TO ANALYZE THE COMMERCIALS IN PART 1: Techniques of Persuasion: This list comprises common techniques used in political advertising. The list is compiled from an activity on political advertising from the PBS website and the textbook used for this course. (For use with part 1, question 3 & 4) Appeal to Authority: cites an authority who is not qualified to have an expert opinion; cites an expert when other experts disagree on the issue; cites an expert by hearsay only. (Firemen support Jones as the best choice for our town’s future.) Grinnell Living Room Candidate: [PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION CAMPAIGN COMMERCIALS] Appeal to Force: predicts dangerous outcomes if you follow a course other than the speaker’s/writer’s. (This kind of economic policy will lose you your job—and hurt your children’s future.) Appeal to Popularity: AKA “Bandwagon”; holds an opinion to be valuable because large numbers of people support it. (Polls show that Americans prefer their current health care system.) Attacking the Person: AKA “Name Calling/Ad Hominem”; attacks the person making the argument instead of the argument; attacks the person making the argument because of those with whom he associates; insinuates that the person making the argument would stand to gain by it. (Certainly he is in favor of a single tax—he is rich.) False Dilemma: offers a limited number of options—usually two—when there are really more choices. (Either we continue the failed war against drugs and lose another generation or make marijuana legal.) Hasty Generalization: uses a sample too small to support the conclusion. (We have seen here in Smallville’s widget factory that free trade doesn’t help the American worker.) Slippery Slope: threatens a series of increasingly dire consequences from taking a simpler course of action. (First it is gun show laws, and then they’ll come to confiscate all guns, and then we lose democracy all together.) Card Stacking: present only those facts that seem to prove your point and ignoring the other side. Plain Folks: try to gain the support of “common people” by appearing to be just like they are. Transfer: use symbols, such as the flag or Uncle Sam, to support an issue. Glittering Generalities: using vague statements like “family values” or “change” that have little exact meaning Grinnell