Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote: a Rank Ordering of Electoral

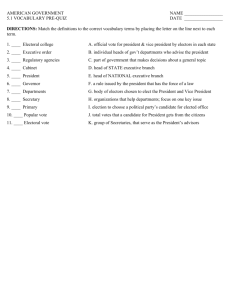

advertisement