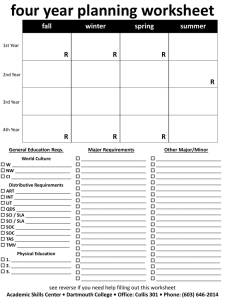

dartmouth college

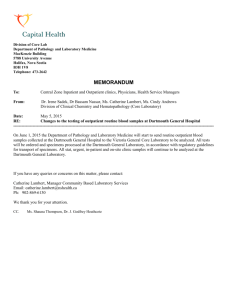

advertisement