ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH

advertisement

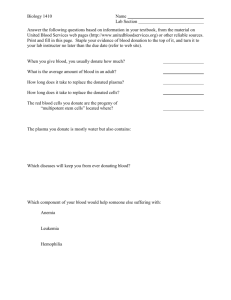

ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Labovitz School of Business & Economics, University of Minnesota Duluth, 11 E. Superior Street, Suite 210, Duluth, MN 55802 Donating to Arts Institutions As Reciprocating Armando Cirrincione, Bocconi University, Italy Francois Colbert, HEC Montreal, Canada Alain D'Astous, HEC Montreal, Canada Literature on donating to arts institutions fails in thoroughly explaining the phenomenon since it has investigated it from the point of view of rewards as incentive to donate. We propose that individuals donate to arts institutions for reciprocating something they perceive to have previously received by the art institution. Thus, a sense of indebtedness and reciprocating generates donating to arts institutions, at least when we consider anonymous donations of small amount. An experimental design tests the basic relationship. Need for self esteem, being keen on arts, need for belonging, perceived efficacy of donating, attitude towards donating, social validation, geographical proximity and type of institution, act as moderator variables. [to cite]: Armando Cirrincione, Francois Colbert, and Alain D'Astous (2007) ,"Donating to Arts Institutions As Reciprocating", in E European Advances in Consumer Research Volume 8, eds. Stefania Borghini, Mary Ann McGrath, and Cele Otnes, Duluth, MN : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 293-295. [url]: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/14009/eacr/vol8/E-08 [copyright notice]: This work is copyrighted by The Association for Consumer Research. For permission to copy or use this work in whole or in part, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at http://www.copyright.com/. European Advances in Consumer Research (Volume 8) / 293 of time because of the benefits they derived from the relationship. Before committing to Dove soap, Ben used Irish Spring because he thought it was more of a “manly soap.” In contrast, he viewed Dove as a “girl’s soap.” However, because of the smell and touch of his skin after using Dove, he is now a devoted consumer. His loyalty to the Dove brand, despite its association with femininity, indicates his high level of commitment to the brand. In addition to the secret affairs and committed partnerships, several informants had “flings,” defined as “short-term, time-bounded engagements of high emotional reward, but devoid of commitment and reciprocity demands” (Fournier, 1998, p. 362). For example, William discovers Is Blue hair gel by “trial and error.” While he likes the product, he explains that he will “switch products if something is not working and something else has a better claim.” Thus, for William, there is little commitment to the brand, and the relationship only lasts until something better comes along. While three of the relationships detailed by Fournier are prevalent in the text, the balance of the consumer-brand relationships did not emerge. However, two new types of consumer-brand relationships were observed. New Consumer-Brand Relationships Observed Among Informants Men engaged in two new types of relationships, which we have labeled “cheap date” and “coach/mentor.” Cheap date is a voluntary relationship, low in affect, which is intensely driven through the consumer’s sensitivity to the cost attached to the brand. Michael states, “I love shoes but I don’t always wear my nice shoes. I wear the same old junk shoes…Watches, same thing. . . I have a really nice watch but what do I wear? My Timex.” Therefore, cheap date is fueled by the informants’ ability to connect with the brand, but only if it meets the criteria that it is inexpensive. Secondly, coach/mentor is defined as a highly affective, intimate relationship, often based on respect and admiration, which provides socioemotional benefits such as assistance in identity construction. The brands most often engaged by the informants as a coach or mentor were James Bond and Indiana Jones. While these are fictional movie characters, Fournier discusses how consumers often view “brands as if they were human characters” (1998, p. 344). Men in this study often discussed Bond with reverence and aspired to be like (and even consume like) the brand. Ben states, “Bond is the epitome of a guy… [he] wouldn’t use Old Spice, he would use some super rare Russian cologne. You can’t get any more manly.” In summary, this paper extends the work of Fournier (1998) by examining its relevance to a particular type of consumer – the male shopper. This study reveals that while the existing typology is useful in explaining some of the relationships men assume when forming relationships with brands, new relationships may be applicable as well. By understanding how men form brand relationships, marketers can develop marketing strategies to effectively appeal to these consumers. Moreover, this research enhances our theoretical understanding of the male consumer who has largely been neglected in past consumer research. References Belk, Russell W. and Janeen Arnold Costa (1998), “The Mountain Man Myth: A Contemporary Consuming Fantasy,” Journal of Consumer Research, 25 (3), 218-40. Bristor, Julia M. and Eileen Fischer (1993), “Feminist Thought: Implications for Consumer Research,” Journal of Consumer Research, 19 (4), 518-36. Byrnes, Nanette. (2006, September 4). Secrets of the male shopper. Business Week, 44-54. Fournier, Susan (1998), “Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research,” Journal of Consumer Research, 24 (4), 343-73. Holt, Douglas B. and Craig J. Thompson (2004), “Man-of-Action Heroes: The Pursuit of Heroic Masculinity in Everyday Consumption,” Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (2), 425-40. Lowrey, Tina M., Cele C. Otnes and Mary Ann McGrath (2005), “Shopping with Consumers: Reflections and Innovations,” Qualitative Marketing Research, 8 (2), 176-88. McCracken, Grant (1988), The Long Interview, Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Otnes, Cele C. and Mary Ann McGrath (2001), “Perceptions and realities of male shopping behavior,” Journal of Retailing, 77, 11137. Peñaloza, Lisa (2001), “Consuming the American West: Animating Cultural Meaning Memory at a Stock Show and Rodeo,” Journal of Consumer Research, 28 (3), 369-99. The Personal Care Occasions Market (2006), “Underlying Embarrassment Inhibits Male Grooming‘’s Growth,” accessed November 30, 2007, [available at www.datamonitor.com <http://www.datamonitor.com/>]. Wells, William (1993), “Discovery-Oriented Consumer Research,” Journal of Consumer Research, 19 (4), 489-504. Donating to Arts Institutions as Reciprocating Armando Cirrincione, Università Bocconi and SDA Bocconi School of Management, Italy Francois Colbert, HEC Montreal, Canada Alain D’Astous, HEC Montreal, Canada Donations for arts institutions are becoming more and more important since public supports are lowering all over the world. Arts institutions are pushed to collect donations by soliciting their audience, but audience seems not to answer their appeals (Chronicle of Philanthropy Survey 2006). Thus growing attention is paid by arts institutions managers towards tools that could effectively foster donations (McNicholas, 2004). Several articles have been published on donating to charities: Andreoni (1990) has explored the relationship between donating and rewards, while others have investigated motivations for donating to charities and the decision process, by using different field methodologies and by considering donations of various amounts (Hibbert, Horne, 1996; Schlegelmilch, Diamantopoulos, Love, 1997; Sargeant, 1999; Bennett, 2003). Nonetheless, findings are sometimes contradictory: for some researches gender matters, while for others 294 / WORKING PAPERS the age is one of the most important factors; some researches underline the role of different types of charities, while other researches stress the role of rewards (social and personal ones). Besides, these researches do not take into account the concept of indebtedness, but they try to gain a better understanding of phenomenon through the use of regressions on public data (Schlegelmilch, Diamantopoulos, Love, 1997) and questionnaires on reasons for donating (Sargeant, 1999; Bennett, 2003). Finally, these researches deal with charities and they do not deal with arts organizations. Although sometimes wide definitions of charities include arts organizations, the latter seem to be quite different from charities in the narrow sense. Charities deal with social aid and assistance, while arts organizations deal with the promotion of culture. Literature on donating to arts institutions is quite poor and it seems to fail in thoroughly explaining the behaviour of donors when small amount donations are taking into account. In fact, this literature has investigated motivations for donating from the point of view of rewards people usually look for in donating (Goodden, 1994; Mathur, 1996; Kottasz, 2004). Thus this literature implicitly supposes that individuals donate to arts institutions because they expect a reward, that is calculated as economic reward (for instance discounts, uses of facilities, free subscriptions and so on), as social reward (joining a social network, gaining social consensus, up-grade social status, and so on) and as psychological reward (self-esteem). This approach to donating could work when we consider donations of high economic value, like bequests or legacies; in these cases it sounds acceptable that donor takes time for deciding and thus he takes into account every kind of consequences, included advantages he could gain from donating to an art institution. But, what does happen when people anonymously donate? Could we really think that individuals act for gaining rewards? For trying to answer these questions, the literature on gift-giving can support us (Malinowski, 1922; Mauss, 1925; Belk, 1979, 1996; Belk and Coon, 1993; Campbell, 1987; Sherry, 1993; Larsen and Watson, 2001). Several papers on gift-giving have been published since the seminal contribution of Sherry (1993), where the author underlined that donating to charities is a form of gift-giving, but no article has investigated the relationship between gift-giving and donating: neither in the literature on gift-giving nor in the literature on donation. We propose to investigate this lost piece of literature. In particular, we propose to adopt the point of view of reciprocating and we hypothesize that individuals donate to arts institutions for reciprocating something they perceive to have previously received by the art institution. It is not necessary that the previous gift from the art institution was directed to themselves: it is relevant that they perceive that a gift has been made towards the social group they feel (or desire) to belong. This would be consistent with the Balance theory (Heider and Newcomb, 1946): as far as individuals feel (or desire) to belong to a group that receives benefits from an art institution, they are induced to donate to it. Our assumption means that not only altruism or self esteem or rewards push people to donate to arts institutions, but firstly a sense of indebtedness and reciprocating generates donating, at least when we consider anonymous donations of small amount. The research uses an experimental design. Dependent variables are the willingness to donate. Independent variable refers to the perception of positive role of the art institution within the social group of belonging; it is measured by using direct questions (answers on a seven point labelled scale). Some constructs act as moderator within this relationship: they are need for self esteem, being keen on arts, need for belonging, perceived efficacy of donating, attitude towards donating, social validation, geographical proximity and type of institution (Figure 1). Need for self-esteem could moderate the relationship, since both reciprocating is perceived as a social desirable behaviour and, through reciprocating, individual confirms to himself his belonging to a specific social group. The concept is referred to self-esteem individual can obtain with respect to group he feels (desires) to belong. I will be measured using the Maslow’s scale. Social validation acts as moderator of the relationship because it states that the role of the art institution is socially recognized, thus it reinforces the perception of positive efforts of institution towards the social group. It needs that social validation comes from the same social group the donor feels to belong. It will be manipulated through the stimulus. Need for belonging acts as moderator since it enhance identification with the social group that is perceived as benefited by the art institution. It will be measured using the Maslow’s scale. Perceived efficacy is recognized in social psychology literature as a moderator of individual action, especially when socially responsible actions are taken into account. It will be measured through specific questions and a labelled scale. Attitude towards donating refers to past experiences of donating or volunteering of the subject or his elatives. It is measured through dichotomous questions. Geographical proximity is referred to geographical proximity. It positively moderates the relationship, but its effect is mitigated by the effect of passion, depending on the international recognisability of the art institution. It will be manipulated through the stimulus. Type of institution could impact on willingness to donate since arts institutions could be basically divided into museums and arts performing institutions. Differences in emotions which could be felt by visiting a museum with respect to listening to a concert or watching a dance can be The experiment uses a questionnaire for testing hypothesis. Questionnaires were built for testing stimuli and moderator variables. Stimuli were associated with a slogan on a fund-raising campaign of an art institution. Questionnaire asked on the efficacy of the slogan for convincing people to donate. The slogan was used just for making the cover story more credible and it is designed in order to remain the same for every experimental group, thus it does not influence the answers. The slogan was “Art needs you”, followed by a request for donating to a museum/orchestra and, eventually, by a sentence that contain the social validation stimulus. Eight different questionnaires were built for testing between groups differences on three variables: type of arts institution (museum/ orchestra), proximity (Montreal and Quebec-City while questionnaires were administered in Montreal) and Social validation (the presence or absence of the sentence “Last year this school’s students were the group of donators who gave the highest amount of money on average per individual to the institution”). Questionnaires have been administered to 280 students (each student received just one questionnaire) (Table 1). Hypothesis we would like to test are the follows: European Advances in Consumer Research (Volume 8) / 295 FIGURE 1 Hp1: Hp1a: Hp1b: Hp1c: Hp1d: perception of efforts done by an art institution towards the group the donor belongs fosters the propensity to donate to that art institution. relationship between efforts done by an arts institution and the propensity to donate is positively moderated by the donor’s need for self-esteem relationship between efforts done by an arts institution and the propensity to donate is positively moderated by the social validation relationship between efforts done by an arts institution and the propensity to donate is positively moderated by the geographical proximity. relationship between efforts done by an arts institution and the propensity to donate is positively moderated by the level of passion. The research is still going on. Questionnaires will be administered on January and February to francophone graduated students of a Canadian university. Findings will be available by may 2007. References Andreoni, J. (1990). “Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glowing Giving,” The Economic Journal, 100 (June), pp. 464-477; Belk R., 1979, “Gift-Giving Behaviour”, in Sheth J.N.(ed) Research in Marketing, Vol.2, pp95-126; Belk R., Coon G.S., 1993, “Gift Giving as Agapic Love: an Alternative to the Exchange Paradigm Based on Dating Experiences”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 20, pp 393-417; Belk R.,1996, “The Perfect Gift”, in Otnes C. and Beltramini R.F. (eds), Gift-Giving: A research Anthology, pp59-84, Bowling Green University Press, Bowling Green; Bennett, R. (2003), ‘Factors Underlying the Inclination to Donate to Particular Types of Charity,’ International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 12-29; Campbell C., 1987, The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism, Blackwell,London; Chronicle of Philanthropy Survey 2006, The Chronicle of Philanthropy Editions, NY; Goodden H., 1994, “An Enormous Inter-Generational Transfer of Wealth is Imminent: How can Charity benefits?”, Front and Centre, Vol.1 (3), pp1-18; Heider F., Newcomb T., 1946, “Attitudes and Cognitive Organization”, Journal of Psychology, vol. 21, pp.107-112; Hibbert, S. and Horne S. (1996), “Giving to Charity: Questioning the Donor Decision Process,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13 (2), pp. 4-13; Kottasz R., 2004, “How Could Charitable Organization Motivate Young Professionals to Give Philanthropically”, International Journal of Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, vol 9 (1), pp.9-28; Larsen D., Watson J.J., 2001, “Guide Map to the Terrain of gift Value”, Psychology and Marketing, vol. 18 (8), pp. 889-906; Malinowski B., 1922, Argonauts of the Western Pacific, Routledge, London; Mathur A., 1996, “Older Adults’ Motivations for Gift Giving to Charitable Organizations: An Exchange Theory Perspective”, Psychology and Marketing, vol. 13 (1), pp. 107-123; Mauss M., 1925, The Gift: Form and Function of Exchange in Archaic Societies, Norton, NY ; McNicholas B., 2004, “Arts, Culture and Business: a Relationship Transformation, a Nascent Field”, International Journal of Arts Management, vol.7, n. 1, pp 57-69;