THE LANGUAGE OF MAN AND THE LANGUAGE OF GOD IN

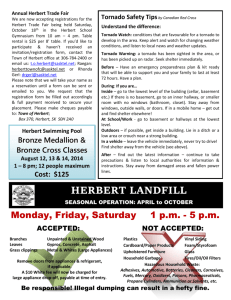

advertisement