The Blessing of Pain

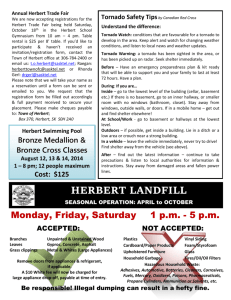

advertisement

Dallenbach 1 Amy Dallenbach Dr. Karen Lee English 260 Survey of British Literature I 8 December 2010 The Blessing of Pain “God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pains; it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world” (Lewis par. 4). A theme throughout the work of many metaphysical poets is the concept of God redeeming pain in order to draw mankind closer to Himself. The writing of George Herbert is no exception. Through physical sickness and emotional pain, Herbert was drawn into a beautiful, deep relationship with his Creator that is intimately expressed in his poetry. His poems “Altar,” “Easter Wings” and “Affliction” contain stunning imagery, innovative form, and symbolic Truth that transcends distance and time. George Herbert was an Anglican priest. His poetry is a form of worship, a way in which he expresses his spirit to God. Critic Ann Townsend writes of Herbert, “His audience is, predominantly, God; he most often speaks directly to God…His predominant lyric voice is the intimate ‘I-You’; he seeks to commune directly with his ‘Master’” (Townsend par. 12). Because of his vocation as a priest, most of Herbert’s poetry contains and relies heavily on Biblical imagery and allusion. His poem “The Altar” likens the human heart to the altar in Jewish temples used to offer burnt sacrifices to God. The poem’s rhyme scheme follows a rhymed couplet (AABBCC etc.) form, with lines 1-2 and 15-16 containing ten syllables, lines Dallenbach 2 2-4 and 13-14 containing eight, and lines 5-12 containing four, respectively. In this way, Herbert causes his poem to take on the visible form of an altar. This is called emblem or pattern poetry. Utilizing this visual imagery also aids the reader in understanding the main concept that Herbert is trying to communicate. “The Altar” is primarily a desperate prayer of someone struggling under the yoke of spiritual discipline. The speaker confesses that his heart has become as hard as stone (lines 6, 10, 14). However, the altar that Herbert writes of is not made of physical stone, but “made of a heart and cemented with tears” (line 2), conveying that the construction of this altar will be accomplished through a process heartache and pain. God’s power has taken, broken, and shaped the stone into smaller pieces (line 8). The speaker then invites God to reshape these broken pieces of his heart into an altar, even if that means engaging violent force to accomplish that end. Literary critic Albert C. Labriola writes, “By his willingness to have his heart reintegrated in the shape of an altar, as he sacrifices the sinful impulses that elicited retribution, the speaker participates in expiation as a prelude to sanctification” (Labriola). More often than not, the heart experiences growth and purification through painful, even excruciating experiences. Yet even so, Herbert writes that this process is worth the pain if it will teach him to share in Christ’s sacrifice and experience greater intimacy with Him (lines 15-16). The last line speaks Herbert’s deep desire for his heart to be cleansed so that he may belong completely to God. In this poem, Herbert draws connections to numerous Scripture references, such as lines 13-14 which echo Luke 19: 40: “‘I tell you,’ He replied, ‘if they keep quiet, the stones will cry out.’” Herbert’s words, “That, if I chance to hold my peace / These stones to praise thee may not cease” (lines 13-14) take this verse a step further. Even if his mouth were to Dallenbach 3 remain silent, his heart – the very core of his being - would still cry out for God. Similarly, Herbert draws on the specifications that God gave Moses regarding the construction of the altar in Exodus 20:25. But instead of building a physical altar where people offer up their sacrifices, the altar Herbert writes of is the human heart. He makes a connection to the New Covenant, where the human body becomes the temple of the Lord (NIV, 1 Corinthians 6.19). If the body is the temple where the Spirit of the Lord dwells, then the heart is the altar within that temple, where people lay down their own wills and desires for the sake of being in a relationship with God. Herbert’s poem speaks of one of the most humbling, astounding concepts in the Christian faith: through Christ’s sacrifice, man not only has access to God’s Spirit, but he also becomes the dwelling place of His Spirit. In other words, people are more than just able to step beyond the veil and into the Father’s presence; through Christ’s blood, their hearts actually become the Holy of Holies. Like “The Altar,” George Herbert’s poem “Easter Wings” is also an emblem poem that discusses the Christian themes of redemption, restoration and resurrection. Although the poem is sometimes printed in the shape of two stacked hourglasses, Herbert’s first publications printed the lines vertically. This allows the waxing and waning length of the poem’s lines to seem more apparently like a pair of wings (West par. 9). Herbert achieves the emblematic wing shape by using an ABABA CDCDC rhyme scheme and by shortening or lengthening each subsequent line’s syllables by two beats. This shape also becomes a visual metaphor for the underlying message of the poem. “Easter Wings” speaks of deterioration and restoration on both a universal and personal level. The first five lines of the poem discuss the tragic decline of the whole of humanity as a result of the fall. Mankind was created out of God’s glorious riches, but then Dallenbach 4 it steadily decays as sin grows (lines 1-5). The next five lines bring renewal as they both restore the length of lines and speak of the redemption that Easter morning brings to humanity (lines 6-10) Similarly, the first section of the second stanza diminishes as Hebert writes of struggles with sin on a personal level. Christ’s death and resurrection bring healing for man on an individual level as well as for all of mankind. Interestingly, both stanzas reach their shortest points, those where they are “most poor” (line 5) and “most thin” (line 15), at the places where man’s power has been completely exhausted. In both stanzas, the poem’s lines begin to lengthen again with the repeated line “With thee” (lines 6, 16). By doing this, Herbert symbolically shows that man can only begin to heal and fly through the strength of the Lord. Christ’s resurrection on Easter morning gives man the power to rise with Him and soar again in His presence. As with “The Altar”, Herbert draws on Biblical allusion to strengthen and deepen the meaning of his poetry. In “Easter Wings,” his second stanza echoes the words of Isaiah 40:30-31: “Even youths grow tired and weary, and young men stumble and fall; but those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint.” Lines 11-14 are a confession of the personal sins of Herbert’s youth and the sickness and shame that still linger as a result of his choices. Specifically, Herbert struggled with consumption, or tuberculosis, throughout his life. Although his sickness was difficult to bear, it became something that ultimately drew him closer to God. The last line of “Easter Wings” reads: “Affliction shall advance the flight in me” (20). Because he was made more dependent on God, Herbert grew to trust Him more and was able to view his sickness as a blessing. His weakness Dallenbach 5 caused him to rely on God and therefore enabled him to have greater access to God’s risen power. The final poem that demonstrates Herbert’s experience with the redemptive qualities of pain is “Affliction.” This poem is a stunning picture of honesty and vulnerability. Throughout the poem, Herbert moves from a state of self-centered autonomy to a genuine, trusting relationship with God through a painful series of events. Critic A.E. Watkins points out, “The role these autobiographical elements play in the spiritual progression from self-absorption to selfless devotion…leads to a necessary reconsideration of selfhood along the way” (Watkins par. 5). Unlike the previous two poems, this work is not an emblem poem. Its form follows a more traditional structure, with eleven six-line stanzas following an ABABCC rhyme scheme. By writing his poem like this, Herbert seems to imply that his pain is simply too deep to birth a metaphor. Instead, the poem meanders along his life experiences, woven together by the thread of pain, and ultimately brings about a new way of thinking. “Affliction” begins with Herbert recalling his early days as a newly converted Christian. When God first won his heart and called him to become a priest, he was surrounded by both physical and spiritual pleasures (lines 5-6). The elaborate fixtures and elements of the church delighted him (lines 7-10). All these carefree things encouraged his mind to hold “no place for grief or fear” (line 16). Herbert’s choice of words throughout these first two stanzas draws connotations of childishness and shallow infatuations that shift with the tide of circumstance. His life at this point was so easy that “there was no month but May” (line 22). This faith is not forced to stand firm or falter because it is not faced with any sort of difficulty or pain. It is fed by “milk and sweetnesses” (line 19), the Dallenbach 6 food of spiritual immaturity (NIV, Hebrews 5.13-14). Here again, Herbert makes an allusion to Scripture, transitioning into the pain that will wean him onto solid food. In the fifth stanza, Herbert begins to describe the suffering that snatched him from his superficial joy. Physical disease began to cause his flesh to complain to his soul, saying, “Sicknesses cleave my bones” (line 25-26). Watkins also notes, “In the double meaning of ‘cleave,’ the ‘Sicknesses’ both penetrate and cling to his bones, making the body a host while dismembering it at the same time” (Watkins par. 3). The sickness clutches the body, but ends up destroying the very thing it requires to survive. This physical sickness symbolizes the way that sin infiltrates and gradually decays the human spirit. Herbert concludes the stanza with the lines, “I scarce believed, / Till grief did tell me roundly, that I lived” (lines 29-30). The presence of pain in his life, at this point, was the only thing reassuring him that he was still alive. Feeling something, even pain, was better than feeling nothing at all. Herbert’s sorrow worsens in the next stanza, as his health continues to deteriorate. Additionally, the friends he had looked to for support during this painful season have also died (line 32). The poet’s plight is reminiscent of Job’s story; he moves from a state of blissful abundance to physical and emotional affliction, “blown through with every storm and wind” (line 35). God took away every possible alternative anchor that Herbert could rely on. Herbert is even miserable in his ministry in the priesthood (lines 39-40). He wishes that he could have just been a regular townsperson and questions God’s presence in his life. As Herbert moves into the ninth stanza, he begins to speak of how God broke him of his self-pity: “Perchance I should too happy be / In my unhappiness” (lines 49-50), God Dallenbach 7 caused him to metaphorically eat his pain and allowed greater sickness to take hold of him. Herbert had grown enthralled with pain and addicted to the idea of his own suffering. He had romanticized the concept of affliction and come to worship his own misery like an idol. God pulled him from this impure adoration by adding to his pain, showing him that there is nothing beautiful or lovely about pain itself. From this realization, Herbert cries out to God in spent desperation, “Now I am here, what thou wilt do with me / None of my books will show” (lines 55-56). His pain has left him in a suspended state of paralysis. He is confused about the purpose of his life and longs for some kind of answer from God. Finding none in the books that he reads, Herbert sighs and wishes that he could become a tree. His life could then produce fruitfulness and some kind of purpose, even if it was only to provide a home for the birds (lines 57-60). The pain has left him exhausted and completely emptied of the shallow feelings of affection that began the poem. Herbert acknowledges that he must be humble before God. He considers resigning from the priesthood and becoming an apprentice to some other profession (lines 61-64), demonstrating that he has projected his own expectations onto God’s will. Since they have not been met, he worries that there is something wrong with him. His pain causes him to question and doubt God’s character. But the stanza ends with a prayer of stunning, frantic honesty: “Ah, my dear God! Though I am clean forgot, / Let me not love thee, if I love thee not” (lines 65-66). Herbert cries out to God to save him from becoming lukewarm, drawing on a Scriptural theme in Revelation 3:16. If he cannot love God with all of his heart, Herbert begs God to remove his ability to love Him at all. Herbert’s pain has brought him to a newfound state of awareness; he has learned what it truly means to love and serve God. Dallenbach 8 The metaphysical poetry of George Herbert expresses the importance of pain in the lives of humanity. It is the tool that shapes the heart of stone into an altar, the fall that teaches the soul to soar on the wings of redemption, and the process of purging that purifies the spirit. Herbert’s own life serves as a metaphor for the universal Truth embedded in his poetry. Through physical and emotional pain, God speaks His mercy and love to the human heart. In this way, He redeems suffering and uses it for good. Pain corresponds with relief; they are two halves of a seed that brings spiritual growth. God allows pain into the lives of mankind so that He may become their Healer. Dallenbach 9 Works Cited Herbert, George. “Affliction.” Norton Anthology of English Literature, 8th ed. Volume B. Ed. Julia Reidhead, et al. W.W. Norton and Company: New York, 2006. 1609-1611. Print. Herbert, George. “Altar.” Norton Anthology of English Literature, 8th ed. Volume B. Ed. Julia Reidhead, et al. W.W. Norton and Company: New York, 2006. 1607. Print. Herbert, George. “Easter Wings.” Norton Anthology of English Literature, 8th ed. Volume B. Ed. Julia Reidhead, et al. W.W. Norton and Company: New York, 2006. 1609. Print. Holy Bible, New International Version. Ed. Daniel I. Block, et al. Tyndale Press: Wheaton Illinois, 1996. Print. Labriola, Albert C. "The rock and the hard place: biblical typology and Herbert's 'The Altar'." George Herbert Journal 10.1-2 (1986): 61+. Literature Resources from Gale. Web. 7 Dec. 2010. Lewis, C.S. “C.S. Lewis Quotes.” ThinkExist.com. <http://thinkexist.com/quotation/god_ whispers_to_us_in_our_pleasures-speaks_to_us/180233.html> 7 Dec. 2010. Townsend, Ann. "The Problem of Sincerity: The Lyric Plain Style of George Herbert and Louise Glück." Shenandoah 46.4 (Winter 1996): 43-61. Rpt. in Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800. Ed. Thomas J. Schoenberg and Lawrence J. Trudeau. Vol. 121. Detroit: Gale, 2006. Literature Resources from Gale. Web. 7 Dec. 2010. Watkins, A.E. "Typology and the self in George Herbert's 'Affliction' Poems." George Herbert Dallenbach 10 Journal 31.1-2 (2007): 63+. Literature Resources from Gale. Web. 7 Dec. 2010. West, David. "Easter-wings." Notes and Queries 39.4 (1992): 448+. Expanded Academic ASAP. Web. 7 Dec. 2010.