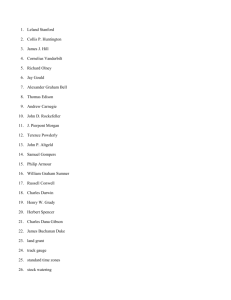

The Rise and Progress of the Standard Oil Company

advertisement