chapter three: a case study of wet, dry and related adjectives

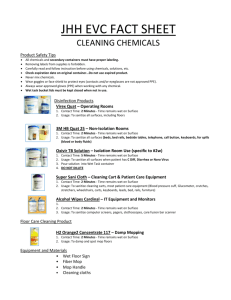

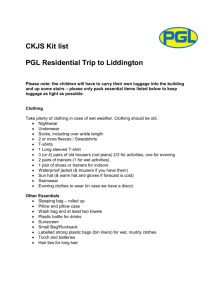

advertisement