Salivary Gland - phenix

advertisement

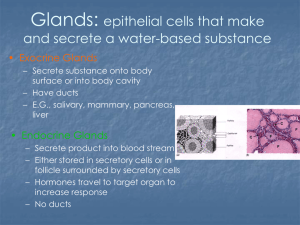

Salivary Gland D. Dunning College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA. Diseases of the salivary glands and ducts are uncommon in the dog and cat, with a reported overall incidence of 0.17 to 0.3% . Reported conditions involving the salivary glands include rupture, inflammation, dilation, necrosis, fistula, a foreign body, autoimmune disease, calculi, and neoplasia. The onset of many of these conditions is frequently insidious, with vague findings on physical examination. Definitive diagnosis often necessitates fine-needle aspiration and cytology, radiology, ancillary imaging, biopsy, and exploratory surgery. Complete knowledge of the anatomy of the head and neck, accurate dissection, removal of the affected glands and duct systems, and drainage may be necessary to successfully treat many of the conditions outlined in this chapter. Anatomy and Function The four major salivary glands in the dog and cat are the paired parotid, mandibular, sublingual, and zygomatic glands.The parotid gland is a triangular bilobar gland located at the base of the horizontal ear canal. The parotid duct runs rostrally along the lateral surface of the masseter muscle between the dorsal and ventral buccal branches of the facial nerve and opens into the oral vestibule at the level of the 3rd-4th and 2nd cheek tooth in the dog and cat, respectively. Secretion from the gland is primarily thin and serous, with a mucous component also present in the dog. Sympathetic innervation is provided by the external carotid plexus of nerves, which travel in tandem with the parotid artery. Fibers of the auriculotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve give parasympathetic input. The parotid artery is the main blood supply to this gland. Venous drainage is via the superficial temporal and great auricular veins. Often mistaken as an enlarged lymph node on cervical palpation, the mandibular gland is located directly beneath the bifurcation of the external jugular vein, lying caudoventrally to the parotid gland, between the linguofacial and maxillary veins. It is an ovoid, capsulated gland that is fused to the monostomatic part of the sublingual gland. The mandibular duct travels rostrally, medial to the digastricus muscle to empty at the sublingual caruncle on the floor of the oral cavity. Secretion from this gland is mixed, both serous and mucous. Sympathetic never fibers reach the gland by means of a perivascular plexus around the glandular artery. Parasymphathetic innervation is provided by the chorda tympani of the facial nerve. The main artery supplying blood is the glandular branch of the facial artery, which enters the gland medially and in close association with the mandibular duct. Entering the dorsal part of the deep surface are one or two branches of the caudal auricular artery. The chief vein draining the gland terminates into the lingual vein. A second smaller vein drains the caudal portion of the gland and terminates in the facial, maxillary, or lingual veins. The sublingual salivary gland is composed of both a monostomatic and a polystomatic component. The monostomatic portion is compact with a fibrous capsule that is contiguous with the rostral border of the mandibular gland. Its duct opens into the oral vestibule near the sublingual caruncle. The diffuse polystomatic part of the sublingual salivary gland spreads into tissues ventral to the floor of the oral cavity and drains via several ducts opening into the oral cavity on either side of the frenulum of the tongue. Similar to that of the mandibular gland, innervation is provided by perivascular plexus around the glandular artery and the 1 corda tympani of the facial nerve. Blood supply to the monostomatic portion is provided by the facial artery; the sublingual artery supplies the small polystomatic part of the sublingual gland. Small satellite veins accompany the facial and sublingual arteries to drain the gland. The zygomatic gland is seated deep to the zygomatic arch, on the dorsolateral surface of the medial pterygoid muscle, forming most of the orbital floor. It has both major and minor ducts that open into the vestibule opposite to the maxillary molar. The zygomatic gland is a mixed salivary gland, ovoid in shape, and is innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve. Several ducts drain this small gland, but the major zygomatic duct opening is opposite the last maxillary molar. The minor duct openings are difficult to visualize with the naked eye, opening just caudal to the major duct. The first branch of the infraorbital artery provides blood supply to the gland. Venous drainage terminates into the deep facial vein on the lateral surface of the gland. In addition to these primary glands, smaller, variable glands are present in the soft palate, lips, tongue, and cheeks and are collectively referred to as buccal glands. These glands drain into the oral cavity via numerous small ducts; the secretion is mixed serous and mucous in character. Secretion of saliva is under control of the autonomic nervous system, which controls both the volume and type of saliva secreted. Salivary secretions serve many functions in the dog and cat, some of which are to lubricate and bind masticated food into a consumable bolus, to solubilize dry food, to flush the oral cavity from debris, to prevent overgrowth of oral microbial population, to initiate starch digestion, and to provide evaporative cooling and maintain core body temperature homeostasis. Specific Disease Conditions Salivary Mucocele (Sialocele) Mucoceles are the most common salivary gland disorder of dogs, but are less frequent in the cat. A mucocele, or sialocele, is defined as the accumulation of saliva in the subcutaneous tissue adjacent to the gland or duct. Unlike a cyst, a mucocele does not have an epithelial lining. True brachial and zygomatic cysts have been reported in both the dog and cat, but these are rare. The exact pathogenesis underlying mucocele formation is usually unknown, but trauma, foreign bodies, and infrequently, sialoliths have been implicated. A case report of a mucocele associated with dirofilariasis has been reported in the dog. Poodles, dachshunds, Australian silky terriers, and Siamese cats may be predisposed. Although a mucocele may arise from any one the salivary glands or their associated ducts, the sublingual and mandibular glands are most frequently implicated. Clinical signs are dependent on the site of saliva accumulation. The most commonly reported clinical sign associated with mucocele formation is the appearance of a soft, fluctuant, painless mass that must be differentiated from abscesses, tumors, and other retention cysts of the neck. Saliva will generally accumulate in a gravity-dependent site, within the cranial cervical or intermandibular region, but it can also appear within the oral cavity under the base of the tongue. The accumulations are referred to as ranulas. A less common site is in the pharyngeal wall, which can obstruct airways and cause significant life-threatening dyspnea and heat stroke. 2 In the initial phases of accumulation, the soft tissue surrounding saliva is inflamed and may be painful on palpation. This stage is short-lived and usually not detected. Once established, the slowly enlarging saliva-filled mass is non-painful; however, secondary infection should be suspected if the mass is persistently painful or a fever is noted. Additional differentials for the swelling in this area include abscesses, neoplasia, and other retention cysts of the neck. A complete oral exam should be performed in the event of a ranula, particularly if oral bleeding is noted. Diagnosis of a mucocele is confirmed via paracentesis of a golden-brown or bloodtinged viscous fluid that typically does not need further analysis. If any question exists regarding the identity of the fluid, a mucus-specific stain, such as a periodic acid-Schiff will confirm the diagnosis. Definitive treatment requires surgical removal of the affected gland and duct. Positioning the animal in dorsal recumbency usually delineates the affected side, as origin of the saliva is typically unilateral and most often originates from the mandibular sublingual gland complex. If the mucocele appears to be bilateral, exploration of the site of swelling will demarcate the side that is affected. The salivary glands may be removed bilaterally without any detrimental effects to saliva production, if any uncertainty remains as to the origin of the saliva accumulation. Treatment limited to lancing and draining or periodic aspiration risks infection, does not address the primary problem, and is contraindicated. A retrospective review of mucoceles in the dog revealed a 42% recurrence rate when treatment was limited to surgical drainage. Aspiration and drainage are indicated with pharyngeal mucoceles, but only as an emergency palliative procedure to relieve dyspnea until the animal can be anesthetized and the offending glands and the redundant tissue blocking the airway removed. If a ranula is present, marsupialization may be necessary in addition to glandular removal and drainage. Treated appropriately, mucocele recurrence is uncommon (less than 5%), unless the glandular tissue is not fully removed. Sialoadentitis Inflammation of the salivary gland, or sialoadentitis, is an incidental finding frequently noted at necropsy in the dog that rarely manifests as a clinical problem. Blunt trauma, mucoceles, penetrating bite wounds, foreign body migration, invasive tumor infiltration, and systemic viral infection have been reported to cause inflammation of the salivary gland. Sialodentitis has been reported with rabies, distemper, and paramyxovirus. Clinical signs are characterized by pyrexia, lethargy, and painful, swollen salivary glands. Severe inflammation can result in abscessation and rupture of the gland into the oral cavity or through the skin, with fistula formation. Sialodentitis of the zygomatic gland frequently results in exopthalmos, retrobulbar swelling, divergent strabismus, and trismus. Mild sialodentitis requires no treatment, and recovery is usually rapid and complete. A salivary abscess necessitates surgical drainage or removal of the gland and therapeutic antibiotics. Fistula Salivary fistulas are typically the result of penetrating injury or abscessation of the salivary gland. The transcutaneous flow of saliva prevents second intention healing. Definitive treatment entails dissection of the fistulous tract and salivary gland removal. In people, botulinum toxin A, injected into the involved gland with ultrasound guidance, has been successfully employed to abate the flow of saliva and allow wound healing via second intention, while preserving the gland in situ. 3 Sialolithiasis Salivary calculi or sialolithiasis is a rare condition; only two cases have been reported in the dog. Clinically, these dogs present with a painful swelling and rupture of the affected parotid gland owing to obstruction of saliva outflow. Diagnosis is made by palpation of the sialolith within the duct, skull radiographs, ultrasound and/or sialography. Treatment entails removal of the calculi, with cannulation and lavage of the duct to remove any residual debris. Healing is via second intention and closure of the duct in not necessary. Sialolith composition is usually calcium phosphate or calcium carbonate. Immune-Mediated Disease Immune-mediated disease localized to the salivary gland is rarely recognized in the dog and cat. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostoma (Sögren syndrome) have been reported in the dog and are seen in association with other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and polymyositis. Necrotizing Sialometaplasia In people, necrotizing sialometaplasia is a benign, mildly painful, self-limiting disease characterized by ischemic necrosis of the palatine gland with secondary proliferation (metaplasia) of the salivary duct. Histologic changes in humans are difficult to differentiate from neoplasia and include: lobular necrosis of salivary tissue, squamous metaplasia conforming to duct and/or acinar outlines, preservation of salivary lobular morphology, variable inflammation, and granulation tissue. In contrast, clinical signs in the dog and cat are characterized by severe acute retropharyngeal pain accompanied by enlarged, hard mandibular salivary glands, anorexia, gagging, and vomiting. The underlying pathobiology is unclear; however, traumatic ischemia is suspected to be the cause of the vasculitis and thrombosis. It has also been hypothesized that this syndrome may be an unusual form of limbic epilepsy. Treatment consists of surgical excision of the affected gland and multimodal pain management or the short-term administration of anticonvulsants for their antiemetic properties. The milder disease in humans is self-limiting; in some cases, facial or pharyngeal pain is more extensive. The prognosis is guarded in the dog, as some animals continue to experience severe pain and vomiting, despite surgical excision and supportive care. The prognosis in cats is more favorable for complete recovery. Neoplasia Salivary gland neoplasia, like all other salivary gland disease, is rare, with an overall incidence of 0.17%. Within the realm of salivary gland disease, however, neoplasia represents a relatively frequent condition, with 30% of all salivary gland biopsies being classified as neoplastic on histopathology. Siamese cats are at higher risk than other breeds of cat, but there does not appear to be a breed predilection in the dog, as previously reported.The glands most commonly affected are the parotid and mandibular salivary glands, accounting for approximately 80% of all the neoplastic cases reported. Clinical signs of salivary gland neoplasia include a mass affect in the region of the gland, dysphagia, weight loss, exophthalmos, and halitosis. The most common histopathologic type of tumor was simple adenocarcinoma in both the dog and cat. Other reported histopathologic tumor types include squamous cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, anaplastic carcinoma, and complex carcinoma. Adenomas are rarely reported and comprise only 5% of all salivary tumors. 4 Fibrosarcomas, lipomas, mast cell tumors, and lymphomas may also incorporate salivary gland tissue by direct extension and invasion. Table 24-1. Distribution of Salivary Gland Tumors in the Dog and Cat. Gland Dog Mandibular 30% Parotid 50% Sublingual and minor glands 12% Zygomatic 4% Indeterminate 4% Cat 59% 19% 6% 3% 13% In general, cats are diagnosed at a later stage of disease than dogs. A retrospective study reviewing salivary gland neoplasia in the dog and cat revealed that early diagnosis significantly improved survival times in dogs but not in cats. In this study, cats seemed to have a more aggressive disease, with over half the feline patients having nodal involvement, distant metastases, or both at the time of diagnosis.2 Furthermore, clinical staging was prognostic in dogs, but not in cats. The median survival times for dogs and cats reported in this multi-institutional study was 550 days and 516 days, respectively. Local infiltration and metastasis to regional lymph nodes and lungs was common, as was local recurrence after surgical excision [2]. Radiotherapy, with or without surgery, offered the best prognosis. References 1. Carberry C, Flanders J, Harvey H, et al. Salivary gland tumors in dogs and cats: a literature and case review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 24:561-567, 1988. 2. Hammer A, Getzy D, Ogilvie G, et al. Salivary gland neoplasia in the dog and cat: survival times and prognostic factors. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 37:478-482, 2001. PubMed 3. Spangler W, Culbertson M. Salivary gland disease in dogs and cats: 245 cases (1985-1988). J Am Vet Med Assoc 198:465-469, 1991. - PubMed 4. Boydell P, Pike R, Crossley D. Presumptive sialadenosis in a cat. J Small Anim Pract 41:573-574, 2000. - PubMed 5. Brown PJ, Bradshaw JM, Sozmen M, et al. Feline necrotising sialometaplasia: a report of two cases. J Feline Med Surg 6:279-281, 2004. - PubMed 6. Durtnell RE. Salivary mucocoele in the dog. Vet Rec 101:273, 1977. 7. Glen JB. Canine salivary mucocoeles. Results of sialographic examination and surgical treatment of fifty cases. J Small Anim Pract 13:515-526, 1972. 8. Jeffreys DA, Stasiw A, Dennis R. Parotid sialolithiasis in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 37:296-297, 1996. 9. Mapes EL. Salivary mucocele in a dog. Mod Vet Pract 65:632-633, 1984. PubMed 10. Mazzullo G, Sfacteria A, Ianelli N, et al. Carcinoma of the submandibular salivary glands with multiple metastases in a cat. Vet Clin Pathol 34:61-64, 2005. - PubMed 11. Schroeder H, Berry WL. Salivary gland necrosis in dogs: a retrospective study of 19 cases. J Small Anim Pract 39:121-125, 1998. - PubMed 12. Brown NO. Salivary gland diseases. Problems in Veterinary Medicine: Gastrointestinal Surgical Complications 1:282-294, 1989. 5 13. Evans HE. The digestive apparatus and abdomen: The salivary gland. In: Miller's Anatomy of the Dog, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1993, pp. 415-419. Available from amazon.com 14. Harvey CE. Salivary gland disorders. In: Mechanisms of Disease in Small Animal Surgery, 2nd ed. Smeak DD, Bojrab MJ, Bloomberg MS (eds). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1993, pp. 197-199. - Available from amazon.com 15. Bellenger CR, Simpson DJ. Canine sialoceles - 60 clinical cases. J Small Anim Pract 33:376-380, 1992. 16. Rahal SC, Nunes AL, Teixeira CR, et al. Salivary mucocele in a wild cat. Can Vet J 44:933-934, 2003. - PubMed 17. Henry CJ. Salivary mucocele associated with dirofilariasis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 200:1965-1966, 1992. - PubMed 18. Karbe E, Nielsen SW. Canine ranulas, salivary mucoceles and branchial cysts. J Small Anim Pract 7:625-630, 1966. 19. Speakman AJ, Baines SJ, Williams JM, et al. Zygomatic salivary cyst with mucocele formation in a cat. J Small Anim Pract 38:468-470, 1997. - PubMed 20. Waldron DR, Smith MM. Salivary mucoceles. Probl Vet Med 3:270-276, 1991. PubMed 21. Stubbs WP, Voges AK, Shiroma JT, et al. What is your diagnosis? Infiltrative lipoma with chronic salivary duct obstruction. J Am Vet Med Assoc 209:55-56, 1996. 22. von Lindern JJ, Niederhagen B, Appel T, et al. New prospects in the treatment of traumatic and postoperative parotid fistulas with type A botulinum toxin. Plast Reconstr Surg 109:2443-2445, 2002. 23. Guntinas-Lichius O, Sittel C. Treatment of postparotidectomy salivary fistula with botulinum toxin. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 110:1162-1164, 2001. - PubMed 24. Mulkey C, Knecht CD. Parotid salivary cyst and calculus in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 159:1774, 1971. 25. Monier JC, Fournel C, Lapras M, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a colony of dogs. Am J Vet Res 49:46-51, 1988. - PubMed 26. Halliwell RE. Autoimmune diseases in domestic animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 181:1088-1096, 1982. 27. Quimby FW, Schwartz RS, Poskitt T, et al. A disorder of dogs resembling Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 12:471-476, 1979. 28. Quimby FW, Jensen C, Nawrocki D, et al. Selected autoimmune diseases in the dog. Vet Clin North Am 8:665-682, 1978. - PubMed 29. Batsakis JG, Manning JT. Necrotising sialometaplasia of major salivary glands. J Laryn Otol 101:962-966, 1987. - PubMed 30. Brooks DG, Hottinger HA, Dunstan RW. Canine necrozing sialometaplasia: A case report and review of the literature. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 31:21-25, 1995. PubMed 31. Stonehewer J, Mackin AJ, Tasker S, et al. Idiopathic phenobarbital-responsive hypersialosis in the dog: an unusual form of limbic epilepsy? J Small Anim Pract 41:416-421, 2000. - PubMed 32. Sneige N, Batsakis JG. Necrotising sialometaplasia. Ann Otol Rhinol Larnyngol 101:282-284, 1992. 6