Unmarried Parents in College

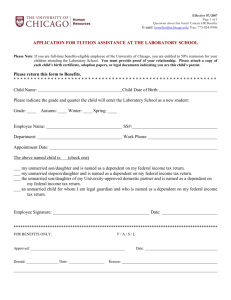

advertisement