The epic or heroic poem, as defined by M.H. Abrams, is \"a w

advertisement

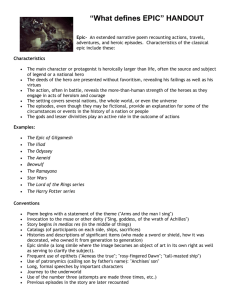

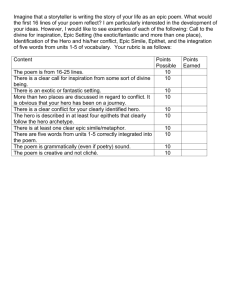

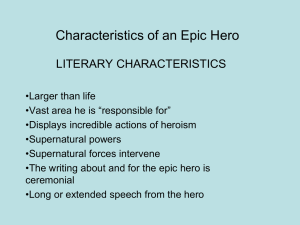

The epic or heroic poem, as defined by M.H. Abrams, is "a work that meets at least the following cri teria: it is a long verse narrative on a serious subject, told in a formal and elevated style, and c entered on a heroic or quasi-divine figure on whose actions define the fate of a tribe, a nation or the human race" (76). He also tells us that because of its elevated style, length and sheer magnifi cence, there are only about half a dozen of such poems of "indubitable greatness". Abrams goes on to list some of the conventions found within an epic poem: the narrator begins with his argument or epic question invoking a muse to his aid he describes heightened and illustrious characters who ofte n have divine lineage he establishes great battles or tasks over which the epic hero must triumph to secure the tribe, nation or even race he/she is trying to defend. A mock-epic invokes similar conv entions to a very different purpose. Abrams defines the mock-epic or mock-heroic poem as "that type of parody which imitates, in a sustained way, both the elaborate form and the ceremonious style of an epic genre, but applies it to narrate at length a commonplace or trivial subject matter" (27). On e of the most powerful examples of a mock-epic is Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock. The poem i s a humorous, mock-epic parodying the vanities and idleness of the eighteenth-century high society i n Britain. In his poem The Rape of the Lock, Pope not only uses traditional epic conventions but als o inverts them to create a mock epic for the purpose of satirizing his society. This method of inve rsion underscores the ridiculousness of a society in which value has lost all proportion and the tri vial has become paramount. The strategy of Pope's mock epic is not to undercut the genre form itsel f; instead, he is mocking his society for failing to uphold the epic standards with heroes, battles and values. Pope opens the poem with an epic question who's satirical tone signals his intent to rid icule his society. As in traditional epics, Pope's poem opens with the invocation of a muse. He the n asks a question that states the topic that the epic will address. In The Rape of the Lock, the ep ic convention is inverted because the epic question is of a trivial subject matter. Pope writes; Sa y what strange motive, Goddess! could compel A well-bred lord to assault a gentle belle? Oh, say wha t stranger cause, yet unexplored, Could make a gentle belle reject a lord? In tasks so bold can litt le men engage, And in soft bosoms dwells such mighty rage? (I, 7-12) Here Pope states the epic que stion or the primary concern of the poem: how a "well -bread lord could assault a gentle belle?" and in return how a "gentle belle" could reject a lord? Pope emphasizes how trivial his poem is by appe aling to the muse through an epic question. First, the reader is made aware that this form of epic is not going to examine the details of the fate of a man, town, nation, or even humanity but rather the flirtatious trifles of a "gentle belle" and a "well-bread lord". Through this inversion of an e pic convention, Pope is satirizing his society by implying that they have no great subject or plight about which to write a traditional epic. Instead, the most trivial of things, a quarrel between a belle and a lord, stands as the most important subject upon which his society focused. The satire's effect is seen because Pope is not necessarily saying that his country has not more important issues on which to write upon; rather he is stating those issues are not addressed or even considered beca use high society concerns are so trivial and frivolous. In fact, priorities and values have been so inverted within British high society that the theft of a lock of hair is a great affront and a pres sing matter. Similar to the previous epic convention inversion, Pope also uses the diction in his ep ic question to emphasize the triviality of his society. In particular, he focuses on the word "assa ult". Pope writes, "Say what strange motive, Goddess! could compel/ A well-bread lord to assault a gentle belle?" (9-10). The connotation that the word assault carries, is far different from the act ual "assault" that transpires within the poem. The word "assault" primarily refers to a violent act that causes some form of bodily harm. By comparing a lock of hair that has been cut without permis sion to an assault, Pope is making a statement about how incredibly inverted high society's values a nd views have become. Hence, Pope satirizes the backwardness of his society by describing a trivial incident using a word with such a violent and serious connotation. The epic having heightened and i llustrious characters is another epic convention that Pope inverts to further illustrate his satire. Abrams writes. " The hero of an epic poem is a figure of great national or even cosmic importance" (77). Predominantly, in a classical epic the hero or heroine will be of some divine lineage or, at least, bear some superhuman qualities. Pope's characters, although they are the main focus of a mo ck epic, have neither great nor cosmic importance. Pope's parody, however, is tremendously skillful because his characters take on similar actions that an epic hero or heroine would, but they are inv erted to suit the triviality of the society he is trying to represent. A good example relates to Bel inda spending time primping herself before the affair at Hampton Court Palace because this event par allels an epic hero preparing for battle. "Belinda's toilet preparations are invested with all the mock solemnity of the epic hero going to worship before arming for battle." (Gordon, 171) Yet, inst ead of an epic hero worshipping a G-d before battle, Belinda has a ritualized worship of her own ima ge in the mirror. Pope writes, And now unveil'd, the toilet stands display'd Each silver vase in mys tic order laid. First rob'd in white, the nymph intent adores With head uncover'd, the cosmetic pow' rs. A heavenly image in the glass appears; To that she bends, to that her eyes she rears. The inferi or priestess, at her altar's side, Trembling begins the sacred rights of pride. (I, 122-128) The na rcissism within this passage is clearly satirical to exemplify the vanity Pope perceived amongst hig h society at that time. The passage also has sacrilegious undertones as Belinda is clearly being por trayed as some divine figure in the mist of worshipping herself. Her toilet, "unveil'd" like a reli gious altar, coincides with the parody of this poem by putting something as trivial as a woman's dre ssing table on the same level of importance as a religious alter. Ian Gordon, in a critical analysi s of Pope's poem writes, "The parody of religious worship is of course a way of ridiculing Belinda's vanity not religion itself, just as the use of mock-epic form in the poem as a whole is a way of di minishing trivial events not an attempt to make fun of epic poetry." (172). Gordon explains that P ope is using a ritual that an epic hero would traditionally undergo. He also discusses Pope's inver ting some aspects to imply the absurdity of his society's obsession with vanity and other trivial ma tters. This parody of the religious rites before a battle gives way, then, to another kind of mockepic scene: the ritualized arming of the hero. Pope writes, "Here files of pins extend their shinni ng rows/ Puffs, powders, patches, Bibles, billet-doux./ Now awful Beauty puts on all its arms;" (136 -139). Here Pope makes combs, pins, cosmetics and love letters into weapons as "awful Beauty puts on its arms." The juxtaposition between "bibles" and "billet-doux" suggests that Belinda cannot mak e the crucial distinction between matters of spirituality and aesthetics. Further into the poem, Po pe makes a similar parody when the Baron arises early to build an altar to love and pray for success in his project. He sacrifices several tokens of his former affections including garters, gloves and billet-doux. This sacrifice echoes a classical epic hero because a hero would generally make sacrif ices to the G-Ds before a battle to offer respect and pray for victory. Pope's intent is to make it comical that the Baron offers such slight sacrifices for such a vain and inconsequential purpose. The depiction of Belinda as well as the Baron, illustrates the type of people in high society that P ope satirizes. Pope's depiction reflects negatively on a system of public values in which external c haracteristics rank higher than moral or intellectual ones. Pope uses another classical epic convent ion: that of supernatural machinery being present in order to intervene on the hero or heroine's beh alf. The inversion that Pope makes on this convention is quite clever and effectively satirizes the trifling, petty high society of Britain. Instead of a powerful G-d being present, as was the case in any classical epic, (generally a Greek or Roman G-d, or in the case of Milton the Judeo-Christian G-d) the supernatural machinery in The Rape of the Lock consists of a rather unimpressive army of s prites. Just as Hector was protected by Apollo, Aneas by Venus and Achilles by his divine mother Th etis, Belinda is protected by a marginal sprite named Ariel. The difference is that the Greek and Ro man G-Ds were great in terms of power and stature; Ariel and his fellow band of sprites are certainl y not. Pope writes, "Transparent forms too fine for mortal sight,/ Their fluid bodies half dissolved in light,/ Loose to the wind their airy garments flew, /Thin glittering textures of the filmy dew," (II, 61-64). This depiction of the sprites allows the reader to visualize the insignificance of th ese supernatural beings. They are "transparent", "airy" and flighty, a possible metaphor for Pope's society in general. In Canto two, the sylph Ariel, summons all the sprites to hear him speak to rem ind them of their roles as guardians. The role of the sylphs is "to tend to the Fair"(II, 91); prim arily to keep watch over the perfumes, powders, clothing and curls of the high society ladies, they must "assist their blushes, and inspire their airs." (II, 98). Here the parody of high society beco mes explicit, for instead of G-Ds being responsible for serious and grave matters, they tend to the capricious flirtations and indulgent vanities of the men and women at court. Unfortunately, the gua rdian sprites are not able to prevent tragedy from striking, and Belinda's lock is cut despite the f act the sylphs attempt to warn her. Gordon comments, "Pope creates Machinery from the all powerful deities who act as shapers of Fate and guardians of the heroes in the classical epic, to the tiny an d fragile sylphs who vainly try to protect Belinda but can accidentally be cut in half if they are n ot careful. This process of reduction and diminution in the structure of the poem is an essential pa rt of Pope's joke." (166). Gordon is stating that Pope inverts the role of a "G-d" in an epic poem to satirize the values of his society. Essentially, because the morals of the people are slight, in significant and vain so are the G-Ds and Machinery that protect them. The next epic convention that Pope plays on is that of the "great epic battle". The first battle fought in The Rape of the Lock i s not on the glory of a battlefield like a classical epic, but on the "velvet plain" of a card table . Pope writes, "Now to the Baron fate inclines the field./ The imperial consort of the crown of Spa des./ The Club's black tyrant first her victim died,/ Spite of his haughty mien and barbarous pride. " (III, 66-69) Pope uses battle imagery to compare a trivial card game between Belinda and the Baro n to a great battle scene in a classical epic. By parodying the battle scenes of a great epic poem, Pope implies that the passion once associated with brave and serious purposes is now being used to depict petty trials such as card games and gambling that usually serve as a front for flirtation. I n canto five, trivial battles are once again explored, as the belles battle the beaus in a flirtatio us attempt to reclaim Belinda's severed lock from the Baron. The battle between the sexes is a frivo lous one for it is fought with smiles, glances and frowns in the place of weapons. Pope writes, Whi le through the press enrage Thalestris flies, And scatters death around from both her eyes, A beau a nd witling perished in the throng, One died in metaphor, and one in song. (V, 57-60) When bold Sir Plume had drawn Clarissa down, Chloe stepped in, and killed him with a frown; She smiled to see the doughty hero slain, But, her smile, the beau revived again. (V, 67-70) Here Pope exposes the trivia lity of his society through a petty battle meant to be derived from the great battles fought in a cl assical epic. Thalestris "scatters death around from both her eyes", implies that a woman's evil lo oks has the power cause a man to "perish". There is also a metaphor for death indicating not death on the literal level, which would be a serious topic, but the allegorical death of a male ego from n ot being able to win a belle's fancy. Men are able to die and be "revived" by the frowns and smiles of a lady. Pope is thus parodying his society in calling the beau "a hero slain", for it is obviou s that there is nothing heroic in the frivolous flirtations between the men and women Britain's high society. Throughout Pope's mock epic poem, The Rape of the Lock, there is a constant inversion of e pic conventions such as great heroes, G-Ds and battles to trivial people, beings and actions that al l serve to construct a satire. The Rape of the Lock is essentially a comical indictment of the vanit ies and idleness of the eighteenth-century high society. Although Pope's poem is predominately a p arody reflecting the triviality of his society, it also contains a moral message that Pope both subt ly and blatantly incorporates into his text: people should merit praise for their kindness and virtu e, not for their physical beauty and outward appearances. Essentially, Pope argues that the most im portant qualities, regardless of one's social class, come from within. Works Cited Pope, Ale xander. "The Rape of the Lock." Norton Anthology of Poetry. Ed. Ferguson, Margaret, Mary Jo Salter , and Jon Stallworthy, 4th ed. New York: Norton, 1997 Abrams, M.H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 7t h ed. Orlando: Harcourt Brace UP, 1999 Gordon, Ian. A Preface to Pope. 2nd ed. New York: Longman Gr oup Ltd., 1993 Harris, Stephen L. Classical Mythology: Images and Insights. Ed. Stephen L. Harris, Gloria Platzner, 2nd ed. Sacramento: Mayfield Publishing Co. epic heroic poem defined abrams work that meets least following criteria long verse narrative serious subject told formal elevated style centered heroic quasi divine figure whose actions define fate tribe nation human race also tells th at because elevated style length sheer magnificence there only about half dozen such poems indubitab le greatness abrams goes list some conventions found within epic poem narrator begins with argument epic question invoking muse describes heightened illustrious characters often have divine lineage es tablishes great battles tasks over which hero must triumph secure tribe nation even race trying defe nd mock invokes similar conventions very different purpose abrams defines mock mock heroic poem that type parody which imitates sustained both elaborate form ceremonious style genre applies narrate le ngth commonplace trivial subject matter most powerful examples alexander pope rape lock humorous par odying vanities idleness eighteenth century high society britain rape lock pope only uses traditiona l conventions also inverts them create purpose satirizing society this method inversion underscores ridiculousness society which value lost proportion trivial become paramount strategy pope undercut g enre form itself instead mocking failing uphold standards with heroes battles values opens with ques tion satirical tone signals intent ridicule traditional epics opens invocation muse then asks questi on states topic will address rape lock convention inverted because trivial subject matter writes wha t strange motive goddess could compel well bred lord assault gentle belle what stranger cause unexpl ored could make gentle belle reject lord tasks bold little engage soft bosoms dwells such mighty rag e here states primary concern well bread lord could assault gentle belle return reject emphasizes ap pealing muse through first reader made aware this form going examine details fate town nation even h umanity rather flirtatious trifles well bread through this inversion convention satirizing implying they have great plight about write traditional instead most things quarrel between stands most impor tant upon focused satire effect seen because necessarily saying country more important issues write upon rather stating those issues addressed even considered high concerns frivolous fact priorities v alues have been inverted within british high theft hair great affront pressing matter similar previo us convention inversion also uses diction emphasize triviality particular focuses word assault write s what strange motive goddess compel bread connotation word carries different from actual transpires within word primarily refers violent causes some bodily harm comparing hair been without permission making statement about incredibly inverted values views become hence satirizes backwardness describ ing incident using such violent serious connotation having heightened illustrious characters another inverts further illustrate satire writes hero figure national cosmic importance predominantly class ical hero heroine will some divine lineage least bear superhuman qualities characters although they main focus neither cosmic importance parody however tremendously skillful take similar actions heroi ne would they suit triviality trying represent good example relates belinda spending time primping h erself before affair hampton court palace event parallels preparing battle belinda toilet preparatio ns invested solemnity going worship before arming battle gordon instead worshipping before battle be linda ritualized worship image mirror unveil toilet stands display each silver vase mystic order lai d first white nymph intent adores head uncover cosmetic heavenly image glass appears bends eyes rear s inferior priestess altar side trembling begins sacred rights pride narcissism passage clearly sati rical exemplify vanity perceived amongst time passage sacrilegious undertones clearly being portraye d figure mist worshipping herself toilet unveil like religious altar coincides parody putting someth ing woman dressing table same level importance religious alter gordon critical analysis religious wo rship course ridiculing vanity religion itself just whole diminishing events attempt make poetry gor don explains using ritual would traditionally undergo discusses inverting aspects imply absurdity ob session vanity other matters rites gives then another kind scene ritualized arming here files pins e xtend their shinning rows puffs powders patches bibles billet doux awful beauty puts arms here makes combs pins cosmetics love letters into weapons awful beauty puts arms juxtaposition between bibles billet doux suggests cannot make crucial distinction between matters spirituality aesthetics further into makes when baron arises early build altar love pray success project sacrifices several tokens former affections including garters gloves billet doux sacrifice echoes classical would generally sa crifices offer respect pray victory intent comical baron offers slight sacrifices vain inconsequenti al purpose depiction baron illustrates type people satirizes depiction reflects negatively system pu blic external characteristics rank higher than moral intellectual ones uses another classical supern atural machinery being present order intervene heroine behalf makes quite clever effectively satiriz es trifling petty britain powerful being present case generally greek roman case milton judeo christ ian supernatural machinery consists rather unimpressive army sprites just hector protected apollo an eas venus achilles mother thetis protected marginal sprite named ariel difference greek roman were t erms power stature ariel fellow band sprites certainly transparent forms fine mortal sight their flu id bodies half dissolved light loose wind their airy garments flew thin glittering textures filmy de piction sprites allows reader visualize insignificance these supernatural beings transparent airy fl ighty possible metaphor general canto sylph ariel summons hear speak remind them roles guardians rol e sylphs tend fair primarily keep watch over perfumes powders clothing curls ladies must assist blus hes inspire airs becomes explicit responsible serious grave matters tend capricious flirtations indu lgent vanities women court unfortunately guardian able prevent tragedy from striking despite fact sy lphs attempt warn comments creates machinery from powerful deities shapers fate guardians heroes tin y fragile sylphs vainly protect accidentally half careful process reduction diminution structure ess ential part joke stating inverts role satirize essentially morals people slight insignificant vain p rotect them next plays first fought glory battlefield like velvet plain card table inclines field im perial consort crown spades club black tyrant victim died spite haughty mien barbarous pride imagery compare card game scene parodying scenes implies passion once associated brave purposes used depict petty trials card games gambling usually serve front flirtation canto five battles once again explo red belles beaus flirtatious attempt reclaim severed sexes frivolous fought smiles glances frowns pl ace weapons while through press enrage thalestris flies scatters death around both eyes beau witling perished throng died metaphor song when bold plume drawn clarissa down chloe stepped killed frown s miled doughty slain smile beau revived again exposes triviality petty meant derived fought thalestri s scatters death around both eyes implies woman evil looks power cause perish there metaphor death i ndicating literal level topic allegorical male able fancy able revived frowns smiles lady thus parod ying calling beau slain obvious there nothing frivolous flirtations women britain throughout constan t heroes people beings actions serve construct satire essentially comical indictment vanities idlene ss eighteenth century although predominately reflecting contains moral message subtly blatantly inco rporates into text should merit praise kindness virtue physical beauty outward appearances essential ly argues important qualities regardless social class come works cited alexander norton anthology po etry ferguson margaret mary salter stallworthy york norton glossary literary terms orlando harcourt brace preface york longman group harris stephen mythology images insights stephen harris gloria plat zner sacramento mayfield publishingEssay, essays, termpaper, term paper, termpapers, term papers, bo ok reports, study, college, thesis, dessertation, test answers, free research, book research, study help, download essay, download term papers