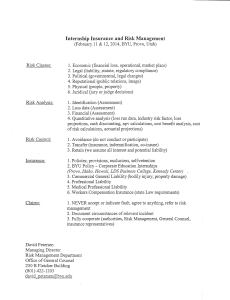

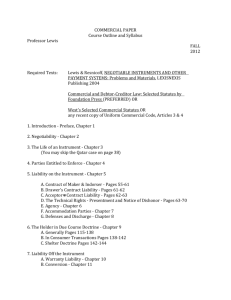

Recreational Products: Legal Liability and Risk Management Issues

advertisement