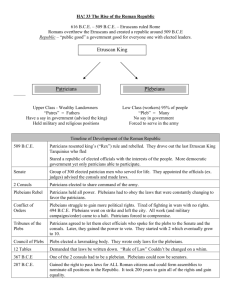

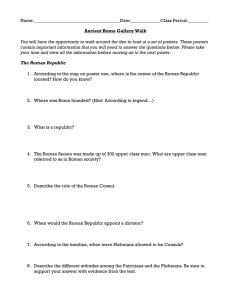

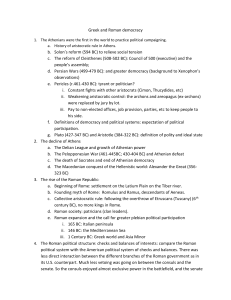

The Constitution of the Roman Republic

advertisement