1

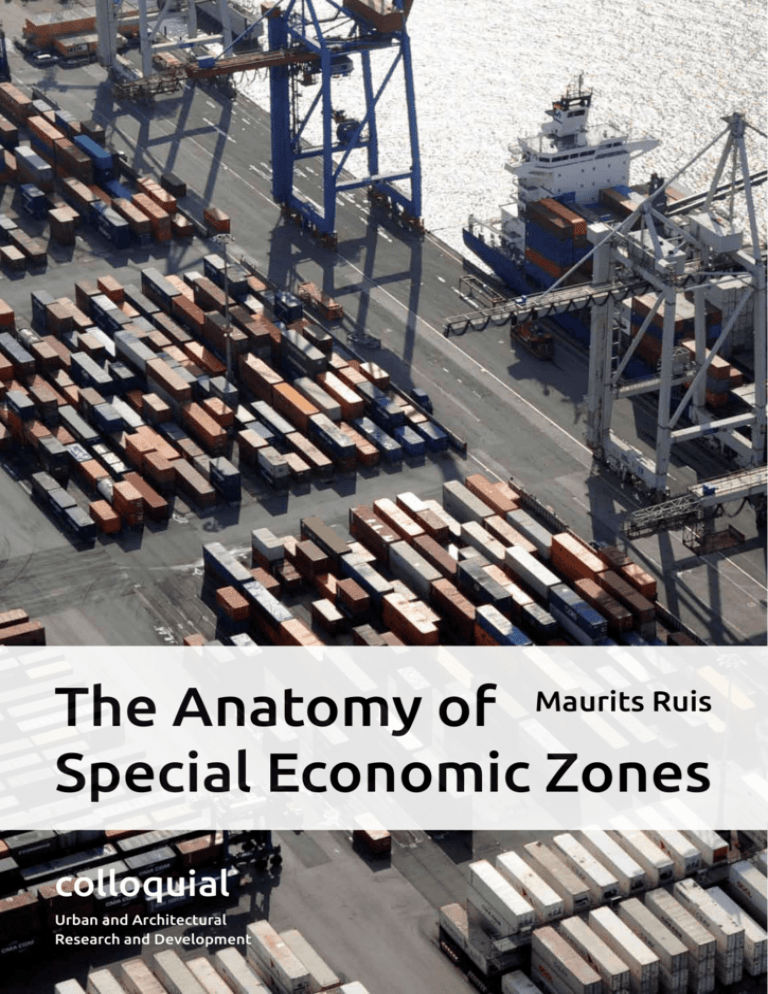

The Anatomy of Maurits Ruis

Special Economic Zones

colloquial

Urban and Architectural

Research and Development

Reading and Printing

This document has been designed for double sided reading and printing.

To view this document double sided in Adobe Reader, select View > Page Display > Two

Page Scrolling, or View > Page Display > Two Up / Continued + Cover Page.

Please consider the environment before printing this document.

Synopsis

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) are areas with a special status that offer special benefits

and a world class environment to get foreign companies to invest. There are currently

3,500 SEZs worldwide, operating in 130 countries, employing 66 million people, and adding over $500 billion of trade related value. SEZs can involve investments up to $900 million, are able to stimulate national economies, and lift millions of people out of poverty.

However, knowledge on what makes a SEZ successful is limited. ‘The Anatomy of Special Economic Zones’ looks at what makes SEZs successful, and is a primer for anyone

involved in their development. For this publication, comprehensive research has been

done of relevant scientific literature, business reports and newspaper articles.

London, November 2012

About the Author

2

Maurits Ruis MSc RIBA is an accomplished architect who has worked on building projects and masterplans for multi-disciplinary, award-winning architectural practices in the

United Kingdom and The Netherlands. His work across scales and sectors and his longtime interest in urban dynamics gave him insight into the requirements of cities on multiple levels. Maurits has an intimate knowledge of the European and Brazilian Markets and

has a strong sustainability background.

Copyright

The Anatomy of Special Economic Zones

Maurits Ruis

Copyright © 2012 by Maurits Ruis

All rights reserved. This publication contains material protected under international copyright laws and treaties. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited. No

part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without express written permission from the author / publisher.

Disclaimer

Although the author / publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information

in this publication was correct at press time, the author / publisher do not assume and

hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by

errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident,

or any other cause.

colloquial

Urban and Architectural

Research and Development

Author: Date: Website: Feedback: Maurits Ruis

November 2012

www.cllql.com

sez@cllql.com

Contents

Introduction5

Definition

7

A Critical History

9

Urban Laboratories

9

Vehicles of Globalization

13

The Export Zone Exported

15

Geopolitical Implications

19

Trial and Error

23

Race to the Bottom

23

Infrastructure as Incentive

27

Comprehensive Clusters

29

Genius Loci

33

Typology

37

Functional I

37

Functional II

40

Organizational40

Political41

Conclusion43

China’s strategic use of Special Economic Zones

43

Special Economic Zones: Vehicles of Localism

47

References51

Bibliography51

Image Credits

55

3

4

Shanghai International Medical Zone (12 sq km). In 2011 more than 100 medical device and biomedical enterprises had settled including Siemens, Draeger, Analogic, Covance, Shanghai Pharma Group and Simcere.

Introduction

It is estimated that there are currently around 3,500 Special Economic

Zones (SEZs), operating in around 130 countries and territories worldwide,

employing around 66 million people, and adding over $500 billion of direct

trade related value (McCallum 2011, ILO 2008). Although these zones

have traditionally comprised single factories with an exempt legal status,

they increasingly comprise complete masterplan developments with $100

million to $900 million of involved investments that are part of a national

economic strategy. Since SEZS gained momentum in the 1980s, they have

become an important factor for local economies and international trade.

SEZs allow multinational corporations to benefit from lower labour costs

overseas and to remain cost-effective in a fiercely competitive international market. They also allow poor countries to industrialise and to take

part in international trade, thereby lifting local workers out of poverty.

An export-oriented growth strategy is often seen as the only remedy to

lagging economic growth, a position that for decades has been promoted

by the IMF, The World Bank, and powerful economists. For development

countries, SEZs offer a direct link to foreign markets and global production networks, and they offer an immediate way to soak up surplus labour

(McCallum 2011).

Not often do SEZs make the front pages, and when they do, it is often

in a negative context. They are often associated with Asian sweatshops

with excessive overtime, underpayment and poor working conditions

(Greenhouse, 2000). This has led to high numbers of employee suicides

in factories in Shenzhen, China, that produce electronic components for

iPads, among other products (Duhigg and Barboza 2012). There are also

the reports of fatal factory fires, such as when 300 workers were killed in a

factory that was locked from the outside in Karachi, Pakistan (Ur-Rehman

et al 2012).

5

6

Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park (25 sq km), ‘Shanghai’s Silicon Valley’, with 110 research and development institutions,

100,000 workers, 3,600 companies including GSK, Roche, Eli Lily, Pfizer, Novartis, GE, AstraZeneca, HewlettPackard, Lenovo, Intel, Infineon, IBM, Citibank, eBay, Infosys, SAP AG, Wison Group, DSM, Henkel, Solvay, Dow,

Dupont, Asia-Pacific Software, Sony, Bearing Point, Kyocera, Cognizant, TCS China, Satyam, Applied Materials.

The modern SEZ is a relatively young concept that is following a steep

learning curve. Through the years, SEZs have developed into complex entities that include industries and services, and that are able to stimulate the

economies of entire regions. Getting involved in their development, as a

politician, investor, project developer, planner or architect, can be a daunting business. This publication will attempt to help all parties involved by

looking at the factors that make SEZs successful and by identifying best

practices. To achieve this, a comprehensive study has been undertaken of

scientific papers, business reports and newspaper articles.

China in particular has been very successful in the development and application of SEZs. Therefore much of the attention in this guide will therefore go to Chinese policies and practices. First we will have a look at the

modern history of the SEZ, and then we will look at the process of trial

and error that has added complexity to the SEZ concept throughout the

years. Then an overview will be provided of SEZ typologies, followed by a

conclusive chapter.

Definition

There are many types of SEZs nowadays, with diverging scopes and scales.

The features that all SEZs share is that they are geographically delimited

areas with an exempt legal status, that aim to attract foreign capital and

generate jobs by offering special incentives to foreign companies. The

zones are usually physically secured and have a single management or

administration. A SEZ normally operates under more liberal economic laws

than those typically prevailing in the host country (Zeng n.d.). In the case

of China, the SEZs also function as experiments for piloting the implementation of capitalist policies (Leong n.d.) and, as we shall see, they are also

applied for strategic purposes. Generally, the SEZ is seen as purely a political concept whose true purpose is the ‘creation of space’ rather than any

particular activity (Cowaloosur 2011). For the purpose of this document

we will speak of SEZs as the generic term that covers all different types of

zones.

7

Semiconductor Manufacturing Trends, 1960-2005

1960s-1980s: Assembly Abroad

Companies move assembly, testing, and packaging offshore.

A = Design B = Fabrication C = Assembly, Testing, Packaging

8

1980s-2000s: Factories Abroad

Companies began contracting with offshore fabrication plants

to produce components from designs.

2000s-2005: Design Abroad

Some design services are offshored, or a part of global teams

operating in many countries. Complex production chains

develop as designs are fabricated in different locations, and

components are then sent to still other locations for assembly,

testing, and packaging (GAO 2006). The history of semicondutor manufacturing clearly shows the tendency of host countries

to move up the value chain through time.

A Critical History

Special Economic Zones have existed in some way or another for hundreds

of years, but the modern SEZ developed significantly in the period after

the Second World War. In this period, the SEZ has been able to benefit

from growing international specialization, the expansion of the manufacturing activities of transnational corporations and an increasing orientation towards export (ILO 2008). The first known instance of a modern SEZ

was an industrial park set up in Puerto Rico in 1947 to attract investment

from the USA (Dohrmann 2008).

An important catalyst in the development of the modern SEZ was the

introduction of the standardized shipping container in 1956. The container

caused loading cost of cargo to drop from $5.86 per US ton to just under

16 cents (Poston 2006), which made it possible for firms to benefit from

lower labour cost overseas whilst remaining cost-effective. Illustrative

for the dependency of SEZs on shipping containers is the fact that nowadays there are very few landlocked countries that have adopted free zone

regimes (Bost 2011).

The first SEZs appeared in Asia in the 1960s, which would become the

nursery home for the modern SEZ in the years to follow. In these years,

The US semiconductor industry began offshoring intensive manufacturing activities such as assembly to Malaysia, Hong Kong and Taiwan. This

move allowed the semiconductor industry to remain cost-competitive as

new foreign rivals emerged in countries such as Japan (GAO 2006). At that

point, the only benefits for SEZ host countries were the creation of jobs

and income of foreign exchange generated by the exportation of products, but no further benefits to the local economy were provided (Cowaloosur 2011).

Urban Laboratories

Although the first SEZ in Asia was established in Kandla, India in 1965,

9

10

Top: One of China’s first Special Economic Zones: the French Concession in Shanghai

Bottom: One of China’s latest Special Economic Zones: Pudong Financial District, Shanghai

the history of the modern SEZ has very much turned out to be a Chinese

history. China has been instrumental in the development of the modern

SEZ, and has also been most successful in reaping its benefits, growing its

domestic economy significantly, and lifting millions out of poverty. When

India introduced its national SEZ policy in 2005, it was modeled closely

after the Chinese model (Leong n.d.).

Perhaps China’s success with SEZs is owed to the fact that China was not

unfamiliar with the concept of designated areas with an exceptional status. As early as 1557, Macau was rented to Portugal by the Chinese empire

as a trading port, and in 1842, the French, British and American concessions were granted in Shanghai following the 1839-42 Opium War. The

introduction of the modern SEZ in communist China was due to the decision of Deng Xiaoping in 1980 to start using SEZs to experiment with the

free market economy, a move he referred to as ‘crossing the river, feeling the stones one at a time’. To that end, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Xiamen and

Shantou were given the status of Comprehensive Special Economic Zone

(CSEZ) (Leong n.d.).

These newly designated SEZs were deliberately located far from the

center of political power in Beijing to minimize both potential risks and

political interference. The choice of Shenzhen was especially strategic

because of its location across a narrow river from Hong Kong, the principal

area from which China would be able to learn capitalist modes of economic growth and modern management techniques from 1997 onwards,

when Hong Kong’s sovereignty would transfer from the United Kingdom

to China (Zeng n.d.). Ultimately, the SEZ status allowed Shenzhen to grow

from a fishing village with a population of 25,000 into a metropolis of 10

million, making it the largest, and most successful, SEZ in the world today

(Zeng n.d.).

As the Chinese SEZ experiment proved successful, a quick succession of

increasingly sophisticated SEZs followed; respectively 14 Economic and

Technological Development Zones (ETDZs) in 1984, 56 High-Tech Industry Demonstration Zones (HIDZs) in 1988, 15 Free Trade Zones (FTZs) in

1990, 14 National Border and Economic Cooperation Zones (BECZs), 12

National Tourist and Holiday Resorts (THRs) and 35 new ETDZs in 1992,

1 Agricultural High-Tech Industry Demonstration Zone (AHIDZ) in 1997

and 61 Export Processing Zones (EPZs) in 2000 (CADZ 2012). More details

on these different types are provided in the chapter Typology. Because

of their ability to stimulate progress, SEZs in China are nowadays also

used as a way to curb potential political unrest, such as in Lhasa, Tibet,

which acquired an ETDZ in 2001, and in Kashgar, Xinjiang province, which

acquired the status of CSEZ in 2010. Just one year before, Kashgar had

been the scene of ethnic unrest under the Ozgur minority population.

11

12

Shenzhen, one of China’s first Special Economic Zones, in the 1970s (top), and today (bottom)

The national and provincial SEZs in China have played an important role

in the Chinese economy and are regarded as the engine of growth in the

regions. Despite their limited areas, they have greatly contributed to FDI

inflows and trade, especially the processing trade and high-tech exports,

together with industrial output and GDP. They also account for the bulk of

employment provided by China’s foreign funded enterprises. In 2007, 27

years after the introduction of the first SEZs, the total GDP of the major

state-level SEZs in China accounted for roughly 21.8 percent of national

GDP. It has been estimated that the total utilized FDI from the major

national-level SEZs (excluding HIDZs) accounted for about 46 percent of

the national total in 2007. Added together, the total employment of the

seven SEZs , the ETDZs, and the HIDZs accounted for about 4 percent of

total national employment, or 770 million jobs (Zeng n.d.).

Vehicles of Globalization

International trade agreements have allowed SEZs to gain further momentum. The most important driver has been the General Agreement on

Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Multifibre Agreement (MFA) between 1974 and

1994, which imposed quotas on countries for the production of textiles

and garments. Quotas assigned to large established exporters were relatively small, but those assigned to countries with a new, small industry

were substantial. This prompted exporters to move around the world in

search of available quotas, which has worked as a catalyst for the establishment of SEZs in Asia and the creation of millions of jobs in countries

that had little or no export garment industry previously. It also led New

York City to lose much of its traditional garment industry, which shrunk

from 16,000 jobs to 9,000 between 1995 and 2009 (Bagli 2009).

Meanwhile in the 1970s, the oil crisis caused economic turmoil that ultimately led to the rejection of trade agreements such as the MFA. Voters and politicians moved toward the rejection of traditional Keynesian

economics and the adoption of a more liberal approach to the economy,

driven by the belief that free markets provided the answer to economic

difficulties. This led, amongst other things, to the revision of GATT from

1986 to 1993, and its ultimate replacement by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. This move lifted 45,000 existing trade tariffs, the MFA

among them, which was replaced by the WTO Agreement on Textiles and

Clothing (ATC) from 1995 to 2004. The ATC effectively phased out the

quota system that existed under the MFA (Roberts 2004).

Following the end to of the garment quota system imposed by the MFA,

some countries succeeded to capture significant market shares, such as

Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Vietnam (McCallum 2011). China in particular has benefited by establishing 61 Export Production Zones (EPZs) in

2000 to act on this trend. As a result, China’s apparel exports have tripled

13

Number of zones

14

Employment (thousands)

Exports (US$ millions)

China

187

China

50,000

China

145,000

Vietnam

185

Indonesia

6,000

Malaysia

117,013

Hungary

160

Mexico

1,300

Hong Kong

101,500

Costa Rica

139

Vietnam

950

Iran

87,289

Mexico

109

Pakistan

888

Ireland

82,500

Czech Republic

92

UAE

552

Czech Republic

68,626

Philippines

83

Philippines

545

India

49,000

Dominican Republic

58

South africa

535

Algeria

39,423

Kenya

55

Thailand

452

Argentina

36,478

Egypt

53

Ukraine

387

Philippines

32,030

Poland

48

Malaysia

369

Korea

30,610

Nicaragua

34

Lithuania

369

Tunisia

20,544

Thailand

31

Honduras

354

Bangladesh

11,716

Jordan

27

Hong Kong

336

Lithuania

11,404

UAE

26

Tunisia

260

Mexico

10,678

Special Economic Zones Rankings indicate that China is the absolute champion in the application of Special Economic Zones (World Bank 2008).

between 2000 and 2006 from US$36.1 billion to US$95.4 billion. Other

countries, such as Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic and Mexico, have

been strongly affected by international competition and were forced to

diversify. Exports from Costa Rica for example shifted from apparel to

other manufactured products including electronics and pharmaceuticals

(ILO 2008). The process of diversification has given rise to a value chain

across countries that is reflected in varying minimum wage levels today,

with China’s at $250 per month, Indonesia at $135, Pakistan at $80 and

Bangladesh at $48 per month or $1.50 a day (Vidal 2012).

One international trade agreement that still drives the establishment of

SEZs today is the Least Developed Country (LDC) status, which is given

to countries which, according to the United Nations, exhibit the lowest

indicators of socioeconomic development, with the lowest Human Development Index ratings of all countries in the world. This status comes with

certain benefits, like competitive imports of raw materials, grants and

duty-free exports to certain developed countries. Some countries, like

Mauritius, have lobbied hard to retain their LDC status in order to keep

foreign parties interested in investing in SEZs, and successfully so, as it got

China to set up the first SEZ outside its national borders in Mauritius in

2007 (Cowaloosur 2011).

International trade agreements and their subsequent obsolescence gave

further momentum to the spreading of SEZs worldwide. Whereas SEZs

operated in 25 countries in 1975, they operated in 130 countries in 2008

(ILO 2008). The explosive growth in numbers of SEZs as a result of the

liberation of the market earned SEZs the reputation ‘vehicles of globalization’ (McCallum 2011).

The Export Zone Exported

China’s move into Mauritius has served as a stepping stone for the next

stage in the evolution of the SEZ: the move into Africa. SEZs have been

present in Africa ever since 1948, when Liberia opened a free trade zone in

the port of Monrovia. In 1974, when Senegal adopted a free zone regime

for the manufacturing industry, the movement was really launched, and

in 2009, Africa was host to 101 different kinds of SEZs, with Kenya leading

with 33 SEZs (Bost 2011).

SEZs in Africa have historically been multi-activity oriented, driven by a

common and highly opportunistic ‘take all’ approach typical of poorer

countries. Sectoral specialisation around a few targeted activities is virtually nonexistent in Africa, making it impossible for SEZs to achieve economies of scale as a way of reducing costs. This lack of focus is also harmful

in terms of of complementarity, capitalisation and transmission of experience among firms. As a consequence firms tend to operate side-by-side

15

Country/ zone

Total invest-

Start of

Current status

Developers

ment

planning

Zambia, Chambishi

USD 410 million

2003

In operation/

under construction

China Non-ferCopper and

rous Metal Mining copper miningGroup

related industries

Zambia, Lusaka

Subzone

Not available Under construction

China Nonferrous

Metals Corporation

Garments, food

appliances,

tobacco, electronics

Nigeria, Lekki

USD 369 million

2003

Under construction

China Civil Engineering Construction, Jiangning

Development

Corporation,

Nanjing Beyond,

China Railway

Transport equipment, textile and

light industries,

home appliances,

tele- communications

Nigeria, Ogun

USD 500 million for the first

phase

Early 2004

Under construction

Guangdong

Xinguang, South

China Developing

Group

Construction

materials and

ceramics, ironware, furniture,

wood processing,

medicine, computers, lighting

Mauritius, Jin Fei USD 940 million

(originally Tianli)

2006-07

Under construction

Shanxi-Tianli

Group, Shanxi

Coking Coal

Group, Taiyuan

Iron and Steel

Company

Property development, services

(tourism, education, finance),

manufacturing

(textile and

apparel, machinery, high-tech

industries)

Ethiopia, Oriental (Eastern)

2006-07

Under construction

Yonggang (withdrew), Qiyuan

Group, Jianglian

International

Trade, Yangyang

Asset Management, Zhangjiagang Free Trade

Zone (not a shareholder)

Electric machinery, steel and

metallurgy, construction materials

16

USD 101 million

Overview of Chinese Special Economic Zones in Africa (Cowaloosur 2011)

Industry focus

without any form of interaction or collaboration in African SEZs (Bost

2011).

Activities inside African SEZs fall for the most part within low value-added

sectors with a high coefficient of unskilled labour. They differ little from

activities outside the zones, except for their orientation towards exports,

and there is no apparent strategy to boost the range of products toward

middle and high-end technologies. The benefits for local economies are

very limited. What is more, SEZs across Africa are fairly similar from one

country to the next, which reflects the influence of the international consulting firms that have drafted most of them (Bost 2011).

China’s move into Africa is about to change that, and six new Chinese SEZs

are currently in development. This move constitutes a significant departure from the common practice of SEZs being initiated by local governments. In this case, China, as the foreign investor, takes the initiative to

approach local governments for the establishment of SEZs. China takes

on the role that traditionally has been confined to local governments, as

it will deliver considerable infrastructural investments as well. China is

thereby the first to export the SEZ concept: the export zone exported.

China’s infrastructural investments include multibillion-dollar projects

such as hospitals, water pipelines, dams, railways, airports, hotels, soccer

stadiums and parliament buildings, but contrary to Western development

funds, African leaders find it hard to embezzle Chinese funds. Money is

usually held in escrow accounts in Beijing; then a list of infrastructure

projects is drawn up, Chinese companies are given contracts to build them

and funds are transferred to the company accounts. Africa gets roads and

ports but no cash (Economist 2011).

The reasons for China’s move into Africa are plenty. China seeks to benefit from fewer restrictions on its exports to Europe and North America

that comes with the LDC status of many African countries. The relative

uncultivated nature of the African market allows China to move low value

production out of China and into Africa, thereby allowing domestic production to move up the value chain, and releasing pressure in the domestic market in the process. Indeed, most Chinese private ventures that are

active in Africa today are said to be there to escape the ‘pressure cooker

of domestic competition and surplus production’ and to benefit from

‘large markets and relatively less intense market competition from local

firms’ (Cowaloosur 2011).

Already, roughly 800 Chinese state-owned or state-controlled corporations are operating in Africa, with China’s Export-Import Bank funding

more than 300 projects in at least 36 countries. Tens of thousands of small

private companies and entrepreneurs are also on the ground. The value of

17

18

Top: Jin Fei (oringinally Tianli) Special Economic Zone in Mauritius. The first zone financed by the Chinese outside

China, and a stepping stone for branching out into Africa. Bottom: future expansion plans for Jin Fei.

Chinese aid in Africa is now thought to have overtaken World Bank assistance (Behar 2008), although the true value of aid is kept a secret by China

as well as African countries. As a result of China’s involvement, Africa’s

goods exports to China already increased more than 60-fold between

1998 and 2010, compared to a fivefold and threefold increase to the US

and the EU, respectively (Ali and Jafrani 2012).

The main reason for China’s move into Africa though is considered to be

the aim to secure access to natural resources. In recent years, China has

become the world’s top consumer of timber, zinc (with 30% of global

demand), iron and steel (27%), lead (25%), aluminum (23%), copper (22%),

nickel, tin, coal, cotton, and rubber. If China’s per capita GDP (currently

about $6,500) will approach South Korean levels in the next 20 years,

Chinese consumption of aluminum and iron ore will increase fivefold; oil,

eightfold; and copper, ninefold (Behar, 2008). China’s development of six

new SEZs is seen as a way to secure access to these resources (AEO 2011).

Geopolitical Implications

China’s decision to move into Africa has been met mixed responses. Some

observers believe that China is Africa’s only hope for an economic jumpstart, and see it as positive that China combines African development with

its own growth and sustainability.

19

But there are also concerns. One is that China may smother Africa’s

emerging light-manufacturing sector with its demand for cheap, unskilled

labour, and by flooding the African market with cheap household goods

from China. Another concern is China’s more relaxed approach to issues

such as the environment, human rights, and good governance, which could

potentially undo years of foreign aid efforts by other countries. Moreover,

a more relaxed approach to international standards also creates unfair

competition. Transparency International’s Bribe Payers Index for example

says that Chinese companies are more prone to bribery, whereas British

companies are now being held to the recently adopted UK Bribery Act

(Behar 2008).

At worst, China’s move into Africa is viewed as a desperate and ruthless

‘scramble’ to secure energy supplies and natural resources, one that could

trigger a new wave of global conflict and massive environmental destruction (Behar 2008). China’s approach causes anxiety in Western countries in

particular because it differs from the approach taken by Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of which most them are

a member, an approach also referred to at the ‘Washington Consensus’.

The OECD approach aims to reach agreements and then call for other

nations to join them into granting it legitimacy. It is a classic top-down

20 Lekki Special Economic Zone, Nigeria, funded by China.

approach where the OECD, or agencies like the International Monetary

Fund (IMF) or the World Bank, demand that other countries join them,

and in cases where nations do not respond positively, they are penalised

through sanctions. In Africa, financial aid has often come under conditions

of austerity, market liberalization, structural adjustment and democratization. This approach is often criticised as one-sided and beneficial for the

Western partners only, and has caused resentment in African countries in

particular.

China on the other hand follows a principle of non-interference, and does

not impose conditions before granting aid. For the development of Chinese SEZs for example, it is China who approaches African countries with

a proposal (the World Bank reports that over two-thirds of African economies now have a financial agreement with the Chinese). There is greater

host-country customization and state ownership in this approach, a result

that the IMF aims to achieve as well, as it aspires to revitalize its 19 development programs. In that sense, China’s approach may be seen as somewhat humbler, as China poses as a partner rather than a provider of aid.

China’s approach does not necessarily compete with the ‘Washington

Consensus’ model though, as Chinese and Western aid flows tend to be

directed toward different sectors. Western aid to Africa is mainly directed

toward supporting public health programs, democratization efforts,

counterterrorism cooperation, the development of health infrastructure,

and improved regulatory institutions. The Chinese on the other hand

primarily focus on infrastructure projects. China assumes a dual position;

one of peripherality toward the OECD approach, and one of appropriation

towards African states (Cowaloosur 2011).

Of course, China’s approach has its own disadvantages. While African

countries form issue-based coalitions and successfully lobby to secure

preferences and domestic safeguard measures when dealing with the

OECD, the competition for Chinese investment make them individualistic

and drives them apart. This causes a ‘race to the bottom’, in which countries offer ever more attractive benefits to investing corporations at the

cost of the local common good (more on this in chapter ‘Trial and Error’)

(Cowaloosur 2011). Also, China’s fragmented approach and lack of transparency gives rise to a new paradigm of competition rather than consensus, which enforces the idea of a ‘scramble for resources’.

China’s ultimate goal, it has been argued, is to build skyscrapers in Tokyo,

run banks in London and make films in Hollywood. China is learning the

ropes in Africa, where the competition is weak. For the Chinese, Africa is

another stepping stone to a commercial presence around the globe (Economist 2011). In that context, the SEZ continues to be a strategic instrument for the Chinese.

21

22

Top: Thika Highway, Kenya, financed by China. Bottom: billboards announcing the development of Lekki Special

Economic Zone in Nigeria by China. Developments like these cause anxiety amoung Western countries.

Trial and Error

Throughout the years, SEZs have become increasingly complex. Traditionally, low labour cost has been the driver for investments in SEZs, and it still

is the most dominant factor. But as SEZs went from single factories with

a focus on generating foreign exchange with export, to comprehensive

zones seeking to attract direct foreign investment (FDI), other avenues

have been explored to get investors interested in zones. Some of these

avenues have proven to be more effective in attracting investors than others. This chapter will take a look at which factors attribute to the success

of SEZs.

Race to the Bottom

A potential selling point explored by many zones is a more relaxed

approach to workers rights. This approach that has triggered a ‘race to

the bottom’ with work conditions entering a downward spiral, with wages

below minimum standards, excessive compulsory overtime and a lax attitudes towards health and safety standards. Poor working conditions are

sustained by a lack of respect for the freedom of association and the right

to collective bargaining in many SEZs. Issues include legal restrictions on

unionization and union membership, the use of yellow (non-independent)

unions, blacklisting of union officials, interference in the affairs of workers’ organizations, refusal to negotiate, harassment, violence and reprisals, legal restrictions or prohibition on industrial action. In Bangladesh, ‘no

unions or strikes’ is officially publicized as an incentive by SEZs (ILO 2008).

Poor working standards have led to high turnovers of workers in SEZs,

with average careers of seldom longer than five years, exhausting the

local pool of human resources (Farole 2011, McCallum 2011, ILO 2003).

Poor working standards have caused political sentiment at NGOs and

trade unions to turn against SEZs in recent years. They are seen as often

going too far, making corporate accountability impossible and promoting

widespread labour abuse and discrimination. NGOs and unions note that

23

24 Onne Export Zone, Nigeria

SEZs have only rarely achieved their stated goals of social and economic

development, and in cases where they are heralded as successes, like in

China, they point to the deplorable state of labour relations and working

conditions inside the heavily-patrolled factories (McCallum 2011). Competition based on the suspension of workers rights is thus considered to

be an unsustainable business model. It has been argued that more integrated policy approaches for attracting export-oriented FDI, for example

by encouraging tripartite representation on SEZ committees (employers,

workers and public authorities), guaranteeing workers’ rights (including

freedom of association and collective bargaining), and upgrading skills and

working conditions have tended to attract higher quality FDI (ILO 2003,

ILO 2008, McCallum 2011).

Another avenue that has been explored is the offering of various tax

incentives, including inexpensive land, exempWhy are Incentives Ineffective?

tion from export taxes, import duties of raw

materials or intermediate goods, profits taxes,

• A tax exemption is of little benefit if

municipal taxes, property taxes, value added

the company is not making profits,

tax, domestic purchases and national foreign

which is usually the case in the initial

years of operation.

exchange controls, the free repatriation of

•

Firms that are profitable from the

profit for foreign companies and the provision

outset might not have needed

of streamlined administrative services to faciliincentives in the first place.

tate import and export such as rapid customs

• Tax holidays encourage income

clearance (ILO 2008, Zeng n.d.).

shifting from non-tax-exempt

enterprises to tax-exempt companies

Experience has shown however that the use

through transfer pricing of interof incentives packages is generally ineffective.

company transactions.

There is an increasing commonality of incentives • Tax holidays reduce the appeal of

debt financing of capital investment

among zones worldwide, imposing significant

by removing the benefits of interest

costs on government budgets. Incentives also

deductibility. This equity funding bias

do not really benefit companies in SEZs. A tax

is accentuated if dividends of taxexemption is of little benefit if a company is not

exempt firms are also exempt from

making profits, which is usually the case in the

personal income tax.

initial years of operation. Firms that are profit• Tax exemptions tend to benefit

able from the outset on the other hand might

investments with a short-term time

not have needed incentives in the first place.

horizon. Longer-term projects that

• generate profits beyond the tax

In addition, tax exemptions tend to benefit

holiday period do not benefit, unless

investments with a short-term time horizon,

firms are permitted to accrue and

while longer-term projects that generate profits

• defer asset depreciation deductions

beyond the tax holiday period do not benefit.

beyond the tax holiday period.

Tax exemptions also do not benefit investors

• Tax exemptions do not benefit

from many OECD countries that tax income on a

investors from many OECD countries

global basis, unless a ‘tax sparing’ agreement is

that tax income on a global basis,

in place (Farole 2011, World Bank 2008).

unless a “tax sparing” agreement is in

place.

When China gave companies outside the zones

(World Bank 2008)

25

Taizhou Medical HIDZ (10-25 sq km), biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, chemicals production and processing,

26 medical equipment and supplies. Housing Hamner Research Institute, Texas Medical Center, China Pharmaceutical University. In 2010, sales income reached 550 billion yuan. In 2020, this will scale up to 200 billion yuan.

the same incentives that applied to companies inside the zones in 1991,

thereby nullifying the comparative advantage of the SEZs, FDI poured

into the country at even greater levels. This has caused some analysts to

wonder whether SEZ development have paved the way, or actually slowed

down the liberalization process. It has been argued that what contributes

to greater economic growth is a greater scale of liberalization, rather than

increasing the number of SEZs (McCallum 2011, Leong n.d.). This suggests

that whilst the exceptional status of SEZs may be helpful in attracting

foreign companies initially, long term benefits can only be achieved when

this status is suspended once these companies have settled in. SEZs, in

that sense, can be seen as transitional instruments.

Infrastructure as Incentive

Another development in the race to attract foreign investment is the

offering of infrastructure, facilities and services to international standards, such as roads, water, uninterrupted electricity supply, gas, sewerage,

networked and air conditioned buildings, and direct connections to ports

and airports. Indeed, the provision of reliable infrastructure has proven to

be much more effective in the success of zones than offering tax incentives, which cannot make up for poor location, infrastructure and facilities.

In addition, a higher quality environment benefits not only investors, but

workers as well (World Bank 2008, Farole 2011).

27

The provision of world class infrastructure and facilities requires heavy

up-front investments, which has traditionally been provided by local or

national governments. As a consequence, some zones were overdeveloped, much ahead of investor demand. In the

Special Economic Zone

case of the first four comprehensive SEZs in

Facilities and Services

China for example, Zhuhai lagged behind Shenzhen because it overbuilt its infrastructure

• Childcare facilities

beyond sustainable demand as its over-sized

• Medical clinics

airport exhausted its initial capital and became

• Conference centers

a drag on its economy (Zeng n.d.). In another

• Product exhibition areas

example, the Zolic Free Zone in Guatemala con• Commercial centers

structed over 24,000 square meters of factory

• Training facilities

• Shelter plans

space in its first two years of operations, which

sat empty without adequate marketing support. • Repair and maintenance centers

• Common bonded warehouse facilities

A lack of adequate funding has also meant that

• Incubator facilities

many public zones are inadequately maintained

• On-site banking facilities

(World Bank 2008).

• On-site housing

• On-site customs clearance and trade

The need for publicly funded up-front investlogistics facilities

ments changed when the focus of zones shifted

• High-speed telecommunications and

from generating foreign exchange through

Internet services, networked buildings

export to attracting foreign investment directly.

(World Bank 2008)

28 Special Economic Zones in Mumbai, India.

With the direct involvement of private investors, governments were enabled to adopt innovative approaches toward the financing of infrastructure such as public-private partnerships (PPPs). In the early stage of Shenzhen for example, joint ventures and private developers from Hong Kong

helped with developing some basic infrastructure (Zeng n.d.). Although

nowadays many public agencies are still establishing zones, a growing

number of privately owned, developed, and operated zones worldwide

has been a trend over the last 20 years. Today, 62 percent of the 2,301

zones in developing and transition countries are private sector developed

and operated. This contrasts greatly with the 1980s, when less than 25

percent of zones worldwide were in private hands (World Bank 2008).

Because private zones are run on a cost-recovery basis, they are generally

more responsive to tenant needs, and therefore provide a wider range

of property management services and amenities. Many SEZs now include

a host of services, such as childcare facilities, medical clinics, conference

centers, product exhibition areas, commercial centers, training facilities,

shelter plans, repair and maintenance centers, common bonded warehouse facilities, incubator facilities, on-site banking facilities, on-site housing, on-site customs clearance and trade logistics facilities and high-speed

telecommunications and Internet services (World Bank 2008). In addition,

local governments have also started to provide various business services

to many SEZs, including accounting, legal, business planning, marketing,

import-export assistance, skills training, and management consulting.

In Suzhou Technology Park in China, the government offers information

services, laboratories, product testing centers, technology trading rooms,

seed money and the like for start-ups (Zeng n.d.).

Higher quality infrastructure, facilities and services are able to command

higher prices from tenants. In well-run private zones, as much as 50 percent of revenues can be derived from amenities in addition to traditional

rental and sales income of a relatively lower profitability. As a result, private zones generally have been more profitable and have had better social

and environmental track records than public zones throughout the world

(World Bank 2008).

Comprehensive Clusters

Another consequence of an increased involvement of private investors has

been a shift of activities within the zones. Many government-funded SEZs

have traditionally focused on attracting low-quality FDI and low-margin,

cost-sensitive industries, like apparel assembly, in the hope that human

capital could be improved once they have attracted sufficient productive

resources. These zones have found it difficult however to escape the lowvalue-added trap. Benefits for the local economy have proven to be higher

when activities focus on more high-tech sectors such as electronics, and

29

30

Xiangfan, home of Xiangfan EDTZ (5 sq km) for the automobile industry, annual production capacity of 100,000

vehicles.

zones accommodating these activities are increasingly developed through

private parties. This pattern is apparent in the Philippines for example,

as private developers move ‘up-market’ in terms of facilities and services

catering to electronics and ICT operations, leaving government zones

to accommodate apparel, handicrafts, and footwear assembly activities

(World Bank 2008).

The development of high tech clusters has allowed China to no longer

focus on low cost production only and move up the value chain. Whereas

the first Chinese SEZs mainly focused on light manufacturing (such as

textiles and electronics), later generations of SEZs also started to include

real estate, electronics, tourism, pharmaceuticals, technology, R&D, residential, leisure, airports and financing (ILO 2003). Other countries have

followed, and high tech SEZs have been established in Malaysia, Taiwan,

Singapore, and elsewhere. SEZs catering to the software and informatics

services industries have been developed in India, Jamaica, the Dominican

Republic, Mauritius, and elsewhere.

High tech clusters tend to be better in achieving economies of scale that

enable business value chains, production specialization, division of labour

and effective local government support. High degrees of networking and

interconnections, and the development of a skilled and specialized work

force that may shift between enterprises, encourages knowledge and

technology spillovers and stimulates productivity and innovation. These

dynamics enable high tech clusters to become centers of knowledge and

technology generation, adaptation, diffusion and innovation, which enables a self-sustaining dynamic. The use of cluster developments to promote economic development by both developed and developing countries

is an approach supported by the development community at large and

has also brought interaction with the local economy, further investments,

infrastructural development, sharing of technology and expansion of R&D

(Cowaloosur 2011, Zeng n.d.).

High tech zones also have a disadvantage however, as the percentages of

female workers tend to drop. In general, zones with light manufacturing

activities tend to employ a mostly female work force. Women make up the

majority of workers in the vast majority of zones, reaching up to 90 per

cent in some of them. Zones thus have created an important avenue for

young women to enter the formal economy at better wages than in agriculture and domestic service. When zones shift toward high tech activities,

these advantages are taken away (ILO 2003). This suggests that a mix of

zone activities of light manufacturing as well as high tech will provide the

best results for local economies.

Main growth opportunities are now said to be in services sectors, especially information and communication technology (ICT), business services,

31

32 Kunming Tourist Holiday Resort (THR) Special Economic Zone, China

and more knowledge- and research and development (R&D) intensive sectors. This requires fostering innovation, which emphasizes the the importance of skills development and training, as well as the need for zones to

avoid becoming enclaves (Farole 2011).

Genius Loci

The success of SEZs is increasingly measured not only by the income of

foreign exchange they generate, but also by the benefits they deliver

for the local economy, a connection that is also referred to as ‘backward

linkage’. Generally, benefits for the local economy and local entrepreneurs are limited because of the very nature of zones. SEZs are created

to attract foreign firms because domestic firms are not competitive internationally. Thus, domestic firms are behind in their capacity to provide

low-cost, high-quality inputs to production in SEZs. Also, incentives that

are available within the SEZs are not available to firms outside of the SEZs,

which puts domestic firms in a competitively disadvantageous position

from the start (Milberg and Amengual 2008).

Another aspect of unfair competition is the fact that the products from

SEZs have the potential to push local manufacturers out of the market.

In Africa for example, Chinese exports consist mostly of mass quantities of low quality and cheap textiles, footwear, electronics, machineries

and plastics. The fear is that once China will establish SEZs in Africa, this

dynamic will be enforced, as the possibility to ‘export’ products from

within the zones to outside the zones will be made much easier. Benefits

for the local labour market are also believed to be quite limited, as an

overlap of manufacturing activities will often cause a shift in labour forces

rather than create a new labour force (Cowaloosur 2011).

Local enterprises also tend to be ignored as potential suppliers for SEZ

based firms. Experience with the Chinese SEZ Jin Fei in Mauritius shows

that investors ignore local enterprises as they cooperate among themselves to produce parts of a product, import parts of products from China,

and will seek linkages with Chinese companies outside the zone. Chinese

investors have refused to even buy construction materials from local Mauritian suppliers, and chose to import raw materials from China instead. As

a result, a leading Mauritian producer of construction materials reported a

slump of 68% in its third-quarter profits in 2011 (Cowaloosur 2011).

Viewing SEZs as disconnected from their context and taking a ‘tabula

rasa’ or ‘blank sheet’ approach to their development without taking into

account their context should be exercised with caution. Most governmentdeveloped zones located in remote areas to act as growth poles have

failed to succeed. Apart from their isolated location, causes also include

heavy upfront capital expenditures and poor collaboration between pri-

33

Yangling, China’s only agricultural HIDZ (50-100 sq km), biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries on a site

34 were China’s first farmers settled 4,000 years ago. A connection with local cultural history has proven to be an

important factor in the success of SEZs.

vate and public parties. Most private EPZs and industrial zones in Vietnam

for example, sat vacant because local and national authorities could not

provide road and other infrastructure connections to the site (World Bank

2008).

A better approach is considered to be building upon and nurture existing

economic ecosystems. Local histories of production or business activities

in a particular sector have been proven to attribute to the success of SEZs.

Most SEZs in China are located in the coastal region or near major cities

that have a history or tradition of foreign trading or business and thus

a better linkage to the international market. And Wenzhou, in Zhejiang

province has a long history of shoemaking, dating back to 422 AD, and

has built up local production capacity over time. Inevitably, it is easier to

devise policies for a functioning cluster, and much harder to call a cluster

into existence from scratch (Zeng n.d.).

There are pitfalls to the contextual development of SEZs though. Many

of the Chinese clusters were developed on the model of one product per

village and one sector per town. This approach has been very useful in the

initial stages for fully mobilizing a village’s or town’s resources based on

their comparative advantages, but once they were successful, they found

themselves lacking further competitive strength because of small scale,

limited human and technology resources, and high-level fragmentation.

Towns were actually competing with other towns in the same province or

other provinces. How to integrate these similar sectors throughout a city,

a province, or a region into a larger value chain so that they can achieve

greater economies of scale and have a deeper capacity for innovation is

considered to be a real challenge (Zeng n.d.).

SEZs that have been developed as stand-alone entities whilst ignoring the

local context have led to social tensions in the past, led by farmers experiencing dispossession of their land as well as political parties exploiting the

plight of the farmers for their own political ends. In India, there have been

court cases challenging the setting up of SEZs, especially the legitimacy

of forceful land acquisition on grounds of ‘public purpose’, which was

considered to be insufficiently proven. Nationalistic sentiments have also

came into play, with people taking to the streets and politicians starting

to lament the neo-liberal land grab. Illustrative for the potentially explosive nature of these conflicts is the case of Nandigram, India, where a bid

for the establishment of a chemical hub sparked unrest that left 14 of the

villagers dead (Dohrmann 2008). A more considered approach toward the

local context could help mitigate such tensions.

Contrary to what their reputation as ‘vehicles of globalization’ suggests,

the success of SEZs is in large part dependent on the ‘genius loci’: the

unique local connections and cultural-historic context.

35

Special Economic Zones

in China by Type

Economic and Technological

Development Zones (ETDZ)

36

High-Tech Industrial Development Zones (HIDZs)

Economic Processing Zones

(EPZ)

Typology

As described in the chapter ‘A Critical History, a quick succession of

increasingly sophisticated SEZs were developed in China once the first

experiment with Comprehensive Special Economic Zones (CSEZs) proved

successful. SEZs now include enclave-type zones as well as single-industry

zones; single-commodity zones; and single-factory or single-company

zones (ILO 2003). This chapter will provide an overview of the different

typologies that have been developed and applied in China. Not only has

China developed the widest range of SEZs, it also continues to set the

tone in the evolution of the SEZ. Typologies pioneered by China are being

copied by countries around the world that hope to replicate China’s success in attracting investment, boosting employment, increasing exports

and generating foreign exchange.

Functional I

The definitions provided below are composited from different sources

(Zeng n.d., Linhe 2005, CADZ 2012).

Comprehensive Special Economic Zones (CSEZs) comprise entire cities

or provinces and are highly autonomous in policy making and the determination of incentives to attract foreign investment. The first SEZs in China

were CSEZs (Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Xiamen, Shantou), and specifically aimed

at experimenting with the free market economy (see previous chapter).

Economic and Technological Development Zones (ETDZs) differ from

CSEZs in their scale, as they are much smaller. Also known as national

industrial parks, ETDZs are multi enterprise zones that offer an investment climate and infrastructure at international standards. Contrary to

EPZs, which focus on manufacturing, ETDZs focus on attracting high tech

industries. Under pressure of local enterprises, preferential tax treatment

was abolished in 2007. By 2010 there were 69 ETDZs (Zeng n.d.).

37

Special Economic

Zones in China by Type

(continued)

Free Trade Zones (FTZ)

38

National Border and Economic

Cooperation Zones (BECZ)

All Special Economic Zones

High-Tech Industrial Development Zones (HIDZs) aim to develop high

tech industries and products and to expedite the commercialization

of research and development by using the technological capacity and

resources of research institutes, universities, and large and medium enterprises, contrary to ETDZs, which only aim to attract high tech industries.

As of 2009, there are 54 state initiated HIDZs in China, which hosted about

half the national high-tech firms and science and technology incubators.

They registered some 50,000 invention patents in total, more than 70 percent of which were registered by domestic firms.

National Agriculture High-Tech Industry Demonstration Zone (AHIDZ)

specifically focuses on the development of new agricultural methods and

technologies in the face of 21st century water scarcity. To date, the only

agricultural high-tech industry demonstration zone is in Yangling (94 sq

km), Shaanxi province, where 4,000 scientists are dedicated to agronomy,

foresting, water management and herding.

Free Trade Zones (FTZs) have three targeted functions: export processing, foreign trade, and logistics and bonded warehousing. FTZs are

enclosed areas with an exempt status and supervised by Customs. Companies in FTZs are eligible for tax refunds on exports, import duty exemption, and concessionary value - added tax. Currently, there are 15 FTZs in

13 coastal cities.

39

Export Processing Zones (EPZs) are similar to FTZs in that they are

enclosed areas supervised by Customs. Whereas FTZs focus on trading and

processing exports, EPZs focus on manufacturing products for export. As

is the case with other SEZs, they aim to offer an environment of international standards that is more practical and efficient and therefore more

attractive to foreign investors that the local context, and through which

they aim to act as catalysts and example for the local economy. So far, 61

EPZs have been set up in China.

National Border and Economic Cooperation Zones (BECZs) are similar

to FTZ, though they are not established in the vicinity of ports or airports,

but located in border towns. Like the FTZ, they aim to develop trade and

local economies (especially those inhabited by ethnic minorities) by allowing processing of products for re-export. 14 BECZs have been approved

since 1992.

National Tourist and Holiday Resorts (THRs) are set up to attract foreign

investment and accelerate the development of the tourist industry. To

date, there are 11 national holiday and tourist resorts realized.

Functional II

Examples of Specialized Zones (World Bank 2008):

Type of

Zone

40

Development

Objective

Size

Typical

Location

Activities

Markets

Example

Technology or Promote

< 50 hectares

Science Parks high tech and

science-based

industries

Adjacent to

universities,

institutes

High technology activities

Domestic and

export

Singapore

Science Park,

Singapore

Petrochemical Promote

Zones

energy industries

100–300 hectares

Petrochemical

hubs; efficient energy

sources

PetrochemiDomestic and

cals and other export

heavy industry

L aem Chabang Industrial Estate,

Thailand

Financial Services

Development

of off-shore

financial services

< 50 hectares

None

O ffshore

financial and

non-financial

services

Export

L abuan Offshore Financial Centre,

Malaysia

Software and

Internet

Development

of software

and IT services

< 20 hectares

Adjacent to

universities,

urban areas

Software

and other IT

services

Export

Dubai Internet City, UAE

Airport-based

A ir cargo

trade and

transshipment

< 20 hectares

Airports

Warehousing,

transshipment

Re-export and Kuala Lumpur

domestic

A irport Free

Zone, Malaysia

Tourism

Integrated

tourism

development

200–1,000

hectares

Tourism areas Resorts and

other tourism

Export and

domestic

Baru Island,

Colombia

A irports,

ports, transport hubs

Re-export

D1 Logistics

Park, Czech

Republic

Logistics

Support logis- < 50 hectares

parks or cargo tics

villages

Warehousing,

transshipment

Organizational

Markusen’s Typology of Industry Clusters (Zeng, n.d.):

Cluster type growth

Characteristics of

member firms

Intra-cluster interdependencies

Prospects for

employment

Marshallian

Small and medium-size

locally owned firms

Substantial inter-firm

trade and collaboration

Dependent on synergies

and economies provided

by cluster

Hub and spoke

One or several large firms

with numerous smaller

supplier and service firms

Cooperation between

large firms and smaller

suppliers on terms of the

large firms (hub firms)

Dependent on growth

prospects of large firms

Satellite platform

Medium-size and large

branch plants

Minimum inter-firm trade

and networking

Dependent on ability to

recruit and retain branch

plants

State anchored

Large public or nonprofit

entity related supplier

and service firms

Restricted to purchaseDependent on region’s

sale relationships

ability to expand political

between public entity and support for public facility

suppliers

Political

The differences between ETDZ/HTIDZ/EPZ/BZ (McCallum, 2011):

Category

ETDZ / HTIDZ

Rate of corporate income

tax

15%

EPZ

BZ

Preferential arrangements of FIE

2 years of exemption and

three years of reduction

by half (7.5%)

Preferential arrangements of enterprises

adopting advanced technology

Reductions up to 3 years

under certain conditions

Preferential arrangePreferential tax rate at

ments for export oriented 10% for the year in which

enterprises

export value exceeding

70%

Duties and importation

VAT for imported selfused production equipments and parts

Exemption granted for

enterprises within the

encourage category

Exemption

Duties and importation

VAT for imported office

appliance and management equipments

No exemption

Exemption

Duties and importation

VAT for imported materials

No exemption except

for bonded materials for

processing trade

Exemption

License for imported

materials, equipments

and office appliance

under processing trade

No exemption except

for encouraged projects

under processing trade

Exemption for all projects

under processing trade

Exemption for all projects

under processing trade

Domestic sale of products Taxed as finished product

comprising bonded raw

materials

Taxed as finished product

Taxed upon imported raw

materials

VAT refund for finished

products made from

domestics

Refund granted only if

finished products leave

territory of China

Refund granted after

domestics enter EPZ

Refund granted only if

finished products leave

territory of China

Bank guarantee bond

under processing trade

Required

Not required

Rate of VAT

17%; 13% for agriculture

Tax refund for re-investment

40% of paid income tax

for the re - investment;

totality of paid income tax

for re- investment in the

case of export oriented

enterprises and enterprises adopting advanced

technology

41

Zhongguancun, ‘Beijng’s Silicon Valley’, 8,000 hi-tech enterprises. 361,000 employees, 5,000 with a doctoral

42 degree, 25,000 with a master’s degree, 180,000 with a bachelor’s degree. Income of 201.4 billion yuan from technology, industry and commerce; total industrial output value 128.7 billion yuan (2001).

Conclusion

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) are areas with a special status that offer

special benefits and a world class environment to get foreign companies

to invest. There are currently 3,500 SEZs worldwide, operating in 130

countries, employing 66 million people, and adding over $500 billion of

trade related value. SEZs can involve investments up to $900 million, are

able to stimulate national economies, and lift millions of people out of

poverty.

China’s strategic use of Special Economic Zones

43

China has not been the first country to apply SEZs, but it certainly has

been most successful in using them, often for strategic purposes. Perhaps

China’s success with SEZs is owed to the fact that China has been historically familiar with the concept of an area with an exceptional status that

accommodates foreign trade partners. As early as 1557, Macau was rented

to Portugal by the Chinese empire as a trading port, and in 1842, the

French, British and American concessions were granted in Shanghai following the Opium War.

The SEZ really took off in China in 1980, when Deng Xiaoping decided to

start using SEZs to experiment with the free market economy, a move he

referred to as ‘crossing the river, feeling the stones one at a time’. To this

end, the cities of Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Xiamen and Shantou were given the

special status of Special Economic Zone. This status allowed Shenzhen to

grow from a village of 25,000 people to a city of 10 million in just thirty

years time, making it the largest, and most successful, SEZ in the world

today.

After the success of the first four SEZs, a quick succession of increasingly sophisticated SEZs followed. In twenty years time, almost 200 new

SEZs were created in China, although they would no longer encompass

entire cities. These new SEZs were mainly focused on accommodating

Top: Lhasa, Tibet; Bottom: Kashgar, Xinjang province, China. Lhasa and Kasgar are cities in poor regions with

44 Bhuddist and Muslim minorities, respectively, that have seen ethnic unrest in recent years. China will develop

Special Economic Zones in both cities in an attempt to address poverty in and curb ethnic unrest.

high tech industries, although also other activities were included. Through

the years, SEZs have been created for car, aircraft, space, financial and IT

industries, as well as for agriculture and tourism.

SEZs have been able to grow local economies significantly, and lift millions

out of poverty. These qualities have led China to apply SEZs in areas that

have been scenes of ethnic unrest. In 2001, Lhasa, in Tibet, got an SEZ, and

in 2010, the city of Kashgar, in Xinjiang province in the West of China, was

given the status of SEZ. Just one year before, Kashgar had been the scene

of unrest among the Ozgur ethnic minority population.

SEZs have also been used by China to foster the relationships with neighbouring countries. Special zones were created in border towns near Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Vietnam to stimulate trade. Special zones

have also been created to stimulate trade with Malaysia and Taiwan. The

Taiwan SEZs in particular has attributed to considerably better relations

between Taiwan and China since 2008.

SEZs have helped China to benefit from changing international trade

agreements as well. When the Multifibre Agreement, regulating garment

quotas, was terminated in 1995, China moved quickly to create 61 special

zones to capture most of the Asian garment industry, and has been very

successful in doing so. Today, China is looking to move into Africa, partly

so it can benefit from the Least Developed Country status of many African

countries, which will allow them to export goods duty-free to developed

countries.

Many argue however that the main reason for China to move into Africa is

access to natural resources. China has announced the development of six

new SEZs in Africa. China will take on the role that is traditionally confined

to local governments, as it will pay for the full package, including considerable infrastructural investments, in return for access. China is thereby

the first to export the SEZ itself: the export zone exported. This move

has caused anxiety with Western partners, who have traditionally taken

a more commanding approach toward African aid. The Chinese approach

could potentially transcend the development of the six SEZs and cause a

shift in geopolitical relations globally.

In the course of 30 years, China has developed the Special Economic Zone

into a strategic instrument that is applicable to a range of issues. SEZs

have allowed China to first sort things out domestically, and now to make

an appearance on the world stage. China’s ultimate goal, it has been said,

is to build skyscrapers in Tokyo, run banks in London and make films in

Hollywood. It is learning the ropes in Africa, where the competition is

weak. For China, Africa is yet another stepping stone to a commercial presence around the globe.

45

Beijing Tianzhu International Airport Free Trade Zone (2008) is the first airport-based comprehensive bonded

46 area in China, with overall planning area 5,944 sq km. It advertises a ‘four-dimensional advantage’, which includes

air, sea, road and railway connections.

Special Economic Zones: Vehicles of Localism

Traditionally, low labour cost has been the driver for foreign companies to

invest in SEZs, and it still is the most dominant factor. Fierce competition

among SEZs worldwide however have led zones to explore new ways of

attracting foreign investors. Some of these ways have proved to be more

successful than others.

A common point explored by zones is offering a more relaxed approach

to workers rights. This means offering wages below minimum standards,

excessive compulsory overtime and a relaxed approach towards health

and safety standards. It also means the prohibition of workers unions, with

some countries openly advertising the absence of unions of strikes. This

approach has triggered a ‘race to the bottom’, in which work conditions

have entered a downward spiral. This in turn has led to high turnovers of

SEZ workers, with average careers of seldom longer than five years, and

exhausting the local pool of human resources. It has also caused negative

sentiments taking hold against SEZs among local populations and NGOs.

Competition based on low working standards can therefore seen as an

unsustainable business model.

Tax breaks are generally seen as helpful for SEZs in persuading foreign

companies to invest, but they have proven to be of little effect on a worldwide scale. In addition, companies are seldom helped by tax incentives.

Tax exemptions are of no value for firms that do not make profits, which

is usually the case in the initial years of operation. The limited duration of

tax holidays means that these companies cannot benefit from tax breaks

once they start to make a profit. Firms that are profitable from the outset

on the other hand might not have needed incentives in the first place.

The offering of roads, water, uninterrupted electricity supply, gas, sewerage, networked and air conditioned buildings, and direct connections to

ports and airports have proven to be much more effective in the securing the success of zones. Many SEZs now also include child care facilities,

medical clinics, conference centers, product exhibition areas, commercial

centers, incubator facilities, training facilities and on-site housing, and

zones also offer financial services, on-site customs clearance, legal assistance and management consulting. The zones that are most successful are

usually run by private parties, which are run on a cost-recovery basis and

are therefore more responsive to tenants needs.

Comprehensive SEZs that offer a wide scope of facilities and services

have allowed countries to move up the value chain and include activities

related to electronics, tourism, pharmaceuticals, technology, R&D, residential, leisure, airports and finance. These cluster developments tend to

be better in achieving economies of scale, which enable business value

47

48

chains, production specialization, knowledge spillovers and effective local

government support that all attribute to a self-sustaining dynamic. Cluster

developments like these have brought interaction with local economies,

further investments, infrastructural development, sharing of technology,

expansion of R&D, and further innovation.

The interaction of SEZs with the local context is another success factor, even though the contained nature of SEZs suggests otherwise. SEZs

are able to nurture and grow the linkage to the international market

that some cities with a history or tradition of foreign trading or business

already have. Many of the successful Chinese SEZs have built upon local

cottage industries that have a tradition of centuries. Zones located in

remote areas that are meant to act a growth poles on the other hand have

involved heavy upfront capital expenditures, and have failed to succeed

nevertheless.

The success of SEZs is traditionally seen as linked with the liberalization of

markets, which has earned them the reputation of ‘vehicles of globalization’. The truth however is that the success of SEZs is not so much dependent on global business models and clever investment strategies. Rather,

the success of SEZs is in large part dependent on local investments in

world quality infrastructure, facilities and services, and a sensitivity to the

‘genius loci’, the unique local connections and cultural-historic context of a

place. In spite of what their reputation of ‘vehicles of globalization’ suggest, SEZs should really be seen as ‘vehicles of localism’.

49

50

References

Bibliography

• African Economic Outlook (AEO) New opportunities for African

manufacturing (2011) http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/en/

in-depth/emerging-partners/industrialisation-debt-and-governancemore-fear-than-harm/new-opportunities-for-african-manufacturing/

• Ali,S. and Jafrani, N. China’s Growing Role in Africa: Myths and

Facts, Carnegie Endowment (2012) http://carnegieendowment.org/

ieb/2012/02/09/china-s-growing-role-in-africa-myths-and-facts

• Bagli, C.V., New York Seeks to Consolidate Its Garment District,

New York Times (2009) http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/20/

nyregion/20garment.html?_r=0

• Behar, R., China Storms Africa, Fastcompany (2008) http://www.

fastcompany.com/849662/special-report-china-storms-africa

• Bost, F., West African Challenges: Are economic zones good

for development?, Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development (OECD) (2011) http://www.oecd.org/swac/

publications/49814045.pdf

• China Association of Development Zones (CADZ), website, (accessed

October 2012) http://www.cadz.org.cn

• Cowaloosur, H., Exporting Zones to Africa: The New Strategy of Asian

Powers, The Nordic Africa Institute, Sweden (2011) http://www.nai.

uu.se/ecas-4/panels/1-20/panel-2/

• Dohrmann, J.A., Special Economic Zones in India – An Introduction,

German Associationfor Asian Studies (2008) http://www.asienkunde.

de/articles/a106_asien_aktuell_dohrmann.pdf

51

• Duhigg, C., Barboza, D., In China, Human Costs Are Built Into an