objectives - Broward Health

advertisement

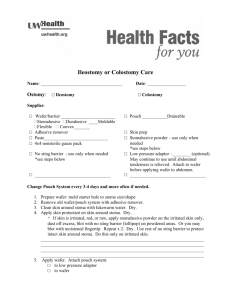

4/9/2014 Indications and Care Essentials for Ostomies Patricia Paxton‐Alan MSN ARNP‐BC CWOCN OBJECTIVES 1 4/9/2014 OBJECTIVES State indications for two different types of ostomies Identify types of stomas based upon: Anatomic Origin (type of ostomy) Surgical Construction (type of stoma) Name two psychosocial issues that affect Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) Discuss current trends in surgical ostomy management, ostomy care, and product advancements 4 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM 6 2 4/9/2014 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM SMALL INTESTINE Length: 20‐25 Feet 4 Layers: Mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa Function: Digestion and absorption of nutrients, vitamins, minerals, fluids, electrolytes, and miscellaneous items such as drugs Neutralizes then converts acid chyme to alkaline for absorption Processes 8 to 10 liters of fluid per day, approximately 1 to 2 liters pass into colon Low pH: pH 6‐7, due to low bacterial count Transit time: 4 to 6 hours 7 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY CROSSECTIONAL VIEW OF LAYERS OF THE GI TRACT 8 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM SMALL INTESTINE (CONTINUED) DUODENUM Length: 20 – 25 cm Location: Distal to Pyloris Function: Neutralize gastric contents, digestion, and absorption JEJUNUM Length: 40 cm Location: After the Ligament of Treitz Function: Major organ of digestion and absorption of fats, proteins, and vitamins 9 3 4/9/2014 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM SMALL INTESTINE (CONTINUED) ILEUM Length: 60 cm Location: Distal to Jejunum Function: Absorption of any nutrients not absorbed by Duodenum and Jejunum Terminal Ileum contains the only receptor sites for absorption of Intrinsic Factor – Vitamin B12 Complex – , and for Bile Salts ILEOCECAL VALVE Size: 2‐3 cm ring of thick smooth muscle Location: Distal to Ileum, between Ileum and Large Intestine Function: To regulate emptying into the Large Intestine, prevent reflux of contents back into Small Intestine Transit Time: Average of 18 – 24 from Ileocecal Valve to Rectum 10 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM LARGE INTESTINE Length: 5‐6 Feet 4 Layers: Mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa Function: Collection, concentration, transport, and elimination of intestinal waste material Absorption of water and electrolytes Motility organ for transporting feces Produces mucous, lubrication of the fecal bolus Common bacterial Flora: Escherichia Coli Aerobacter Aerogenes Clostridium Perfringens Lactobacillus Bifidus Responsible for odor associated with feces 11 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM LARGE INTESTINE (CONTINUED) CECUM Length: 6.0 ‐ 7.6 cm Location: Connects with Ileocecal Valve Function: Receives approximately 1.0 ‐ 1.5 liters of fluid from Small Intestine Appendix arises from posteromedial aspect ASCENDING COLON Length: 15 cm from Cecum to right Hepatic Flexure Function: Water, electrolytes (sodium, chloride), glucose, and urea are absorbed 12 4 4/9/2014 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM LARGE INTESTINE (CONTINUED) TRANSVERSE COLON Length: 45 – 50 cm Fixed: At only 2 points: Hepatic Flexure & Splenic Flexure, highly mobile Function: Consistency of colonic contents change from fluid to semi‐fluid DESCENDING COLON Length: 25 cm Location: Extends from the Splenic Flexure to the brim of the True Pelvis Function: Water, electrolytes, and unabsorbed minerals are absorbed 13 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM LARGE INTESTINE (CONTINUED) SIGMOID COLON Length: 40 cm Function: Water re‐absorption RECTUM Length: 12 ‐ 15 cm Location: Follows curve of Sacrum and Coccyx Function: Storage of feces ANAL CANAL Length: 3 ‐4 cm Location: Extends from Anal Rectal Junction to Anal Verge Function: Elimination of feces 14 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM LARGE INTESTINE (CONTINUED) INTERNAL ANAL SPHINCTER Involuntary Relaxes while External Sphincter contracts allowing sensitive epithelium of the anal canal to “sample” contents to determine if liquid, gas, or solid EXTERNAL ANAL SPHINCTER Voluntary Allows or prevents fecal elimination 15 5 4/9/2014 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GENITOURINARY SYSTEM ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GENITOURINARY SYSTEM 17 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GENITOURINARY SYSTEM KIDNEY Length: 11 cm Width: 5 – 7 cm Right kidney slightly inferior to left due to liver placement Function: Filtration of metabolic waste and toxins from the blood Maintenance of internal homeostasis (maintains normal serum pH between 7.37 and 7.42) Influences blood pressure, vascular volume, red blood cell production, apoptosis, and bone growth maintenance 18 6 4/9/2014 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GENITOURINARY SYSTEM URETERS Length: 24 – 30 cm Left ureter typically longer than right because of the slightly inferior location of the right kidney Function: Pushes a bolus of urine through the ureterovesical junction and into the bladder via peristalsis Ureterovesical junction prevents reflux by sealing the ureter in response to contraction of the bladder 19 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GENITOURINARY SYSTEM BLADDER Muscular, highly distensible organ Length: 12.5 cm Width: 7.5cm Volume: Ordinary amount: 470 cc Ooooo (typical maximum): 600 – 800 cc Function: Storage of urine 20 ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GENITOURINARY SYSTEM URETHRA Length: Female: 3.5 – 5.5 cm Male : 23 cm Function: Provides continence during bladder filling Acts as a sphincter mechanism (entire length in females, proximal end in males) Squeezes when cough or sneeze to help prevent urine leakage 21 7 4/9/2014 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY COLORECTAL CANCER INCIDENCE According to the CDC, in 2008 (the most recent year numbers are available) 142,950 people in the United States were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, including 73,183 men and 69,767 women 52,857 people in the United States died from colorectal cancer, including 26,933 men and 25,924 women Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers in the United States Relative survival rate at 5 years is currently 64.3% in the United States and increasing Approximately 1 million people alive today have a history of colorectal cancer, making this cancer survivor population one of the largest in the United States Approximately 18% to 35% of colorectal survivors have received temporary or permanent intestinal ostomies as part of their treatment 23 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY FREQUENCY AND LOCATION OF COLON AND RECTAL CANCERS 24 8 4/9/2014 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY COLORECTAL CANCER RISK FACTORS Diet Low fiber High animal fat Alcohol Tobacco Age Hereditary syndromes (Lynch Syndrome) Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis) Personal and/or family history of colorectal cancer Polyps (adenoma) 25 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY COLORECTAL CANCER SYMPTOMS Change in bowel habits Diarrhea Constipation Narrowing of stool Incontinence Unexplained weight loss Blood on or in stool Unexplained anemia Abdominal pain or bloating 26 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY CROHN’S DISEASE AND ULCERATIVE COLITIS Cause unknown Possibilities include immune system, virus or bacteria IBD Heredity, genetics may play a role Risk Factors Age, usually before age 30, secondary incidence 50’s to 60’s Ethnicity, whites have the highest risk, may be seen in any ethnic group highest risk in Ashkenazi Jewish descent Family history, higher risk if close relatives, parent siblings, of child History of Isotrentinoin use (previously known as Accutane) Cigarette smoking ‐ most important controllable risk factor for Crohn’s disease Some pain relievers, Advil, Motrin, Aleve, and Aspirin Geographic location, environmental factors, diet high in fat, refined foods people living in northern climates have a greater risk of disease Incidence, highest North America: CD: 20.2/100,00 UC: 19.2/100,000 27 Europe: CD: 12.7/100,00 UC: 6.3/100,000 9 4/9/2014 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY CROHN’S DISEASE AND ULCERATIVE COLITIS DIFFERENTIATION Crohn’s Disease Ulcerative Colitis Transmural Superficial Focal, discontinuous involvement with aphthous ulcers, granulomas may be present Continuous involvement with granularity, friability, and pinpoint ulcerations May affect mouth to anus Limited to colon Rectal involvement variable Rectum always involved Terminal ileum and cecum most commonly involved Small intestine not involved Peri‐rectal abscess/disease may be seen Peri‐anal area normal Bleeding present with colonic disease Rectal bleeding common Weight loss common due to small bowel involvement Weight loss may occur Diarrhea depends on location of disease Diarrhea common as weight loss presents Percent of obstructive symptoms due to fibrosis and narrowing of lumen May have fever and/or night sweats Pain is likely due to transmural inflammation Pain not typical 28 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY CROHN’S DISEASE Normal Colon Crohn’s Disease 29 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY CROHN’S DISEASE 30 10 4/9/2014 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY ULCERATIVE COLITIS 31 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY ULCERATIVE COLITIS 32 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY DIVERTICULITIS Cause Decrease in dietary fiber content Constipation/straining Diverticulosis Begins as diverticula (pouches) form Diverticulitis occurs When diverticula become inflamed and/or infected Likely cause of infectious‐ inflammatory process is stool or food particles becoming trapped in the pouches 33 11 4/9/2014 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY DIVERTICULITIS CLINICAL PRESENTATION Left lower quadrant pain Nausea and vomiting Fever Change in bowel habits Leukocytosis Rectal bleeding 34 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY DIVERTICULITIS Increases in incidence with age, reaching a prevalence of greater than 65% in those older than 85 years. The mean age at presentation with diverticulitis appears to be about 60 years. Significant association between obesity and the risk of developing diverticulitis. Genetics are believed to play a role, in addition to dietary factors. Left‐sided diverticula predominate in the United States. Asians, including Asian Americans, have a predominance of right‐sided diverticula. 35 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY FECAL INCONTINENCE Accidental passing of solid or liquid stool or mucus from the rectum Approximately 18 million in US One in 12 people have fecal incontinence People of any age though more common in older adults and diabetics Slightly more common among women RISK FACTORS Diarrhea, passing loose watery stools 3 or more times a day Urgency, sensation of having little time to get to toilet for bowel movement After pelvic irradiation for malignancy After surgical reconstruction of rectum for irritable bowel or cancer Trauma during childbirth with injuries to pelvic floor 36 12 4/9/2014 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY FAMILIAL ADENOMATOUS POLYPOSIS (FAP) Most common adenomatous polyposis syndrome Autosomal dominant inherited disorder Characterized by the early onset of hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps throughout the colon If left untreated, all patients with this syndrome develop colon cancer by age 35‐40 years Increased risk exists for the development of Other malignancies GARDNER’S SYNDROME Colonic polyposis typical of FAP Along with: Osteomas commonly on the skull and the mandible Dental abnormalities Soft tissue tumors 37 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY ISCHEMIC COLITIS Acute, self‐limited compromise in intestinal blood flow which is inadequate for meeting the metabolic demands of a region of the colon 90% of cases of colonic ischemia occur in patients over 60 years of age Younger patients may also be affected RISK FACTORS Mesenteric artery emboli, thrombosis, or trauma Hypo‐perfusion states due to congestive heart failure, transient hypotension in the perioperative period or strenuous physical activities and shock due to a variety of causes such as hypovolemia or sepsis Mechanical colonic obstruction due to tumors, adhesions, volvuli, hernias, diverticulitis or prolapse There is a long list of medications that predispose to colon ischemia 38 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY VOLVULUS A twisting of any hollow viscus and can occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract In the colon, volvulus can lead to obstruction and sometimes ischemia and perforation Progressive proximal bowel distension occurs as a result of the obstruction, while gas distension of the closed loop increases intra‐luminal pressure over venous pressure leading to vascular congestion and eventual ischemia Twisting of the mesenteric vessels can also produce arterial insufficiency and venous thrombosis Most common anatomic locations for volvulus in the colon are the non‐ fixed regions, specifically the cecum, sigmoid and occasionally transverse portions RISK FACTORS FOR SIGMOID VOLVULUS IN THE U.S. Male gender History of neuropsychiatric disease 39 13 4/9/2014 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY VOLVULUS 40 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY INTUSSUSCEPTION 41 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY RADIATION ENTERITIS DAMAGE DURING OR FOLLOWING THERAPY The combination of acute and chronic radiation injury can result in varying degrees of inflammation, thickening, collagen deposition, and fibrosis of the bowel, as well as impairment of mucosal and motor functions Radiation enteritis is increasing and has been estimated to occur in 2‐5% of patients receiving abdominal or pelvic radiotherapy Reported higher numbers may be explained by the extent of radiation field, the technique, and the dosage of radiation used. Cumulative 10‐year incidence of moderate injuries is estimated at 8%, and that of severe injuries is estimated at 3% Symptoms generally are insidious and develop months to years after therapy has ended Colicky abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting ‐ small bowel obstruction Chronic watery diarrhea Possible development of fistulas 42 14 4/9/2014 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY BLADDER CANCER INCIDENCE According to the American Cancer Society, in 2013 72,570 new cases of bladder cancer diagnosed, including 54,610 men and 17,960 women 15,210 people in the United States died from bladder cancer, including 10,820 men and 4,390 women Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the United States Relative survival rate at 5 years ranges from 15% to 98% in the United States depending upon stage. Early detection is important. In 2010, there were an estimated 563,640 people living with bladder cancer in the United States 43 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY BLADDER CANCER RISK FACTORS Cigarette smoking Chemical exposure, i.e., paints, dyes, rubber, leather, textiles Increasing Age Caucasian Male Previous cancer treatment, i.e., radiation treatment Personal and/or family history Chronic long term bladder infections 44 INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY BLADDER CANCER SYMPTOMS Painless hematuria (may be microscopic) Frequency/urgency Painful urination Pelvic pain Back pain 45 15 4/9/2014 OSTOMIES BY THE NUMBERS The number of patients living with stomas in the United States is unknown, but estimates range up to 450,000 people, with 120,000 new stomas created each year Other estimates predict the number of ostomates to increase by 3% per year Average age for all ostomates is 68.3 years The distribution of procedures is: 36.1% colostomy, 32.2% ileostomy, and 31.7% urostomy Approximately 30% to 40% of ostomies are estimated to be temporary 46 TYPES OF OSTOMIES AND STOMAS TYPES OF OSTOMIES AND STOMAS TYPES OF OSTOMIES Ileostomy ‐ Origin in Ileum Colostomy ‐ Origin in Colon Urostomy – Origin Ileum or Colon May be permanent or temporary 48 16 4/9/2014 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS TYPES BASED UPON: Anatomic location (Ostomy) Ileostomy Colostomy Surgical Construction (Stoma) End Loop Functional Stoma with Mucous Fistula ‐ Double Barrel Continent Stomas (with internal pouches) 50 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS OSTOMY BASED UPON ANATOMIC LOCATION ILEOSTOMY Normal adult output: Often liquid immediately after creation Amount varies between 800 and 1,700 mls/24 hrs Leveling off and gaining consistency in amounts between 500 and 1,800 ml/24 hrs 51 17 4/9/2014 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY ILEOSTOMY Crohn’s Disease Ulcerative Colitis Colorectal Cancer Fecal Incontinence Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Gardener’s Syndrome Congenital Anomalies Trauma (gunshot wounds, etc.) 52 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS OSTOMY BASED UPON ANATOMIC LOCATION COLOSTOMY Normal adult output: Output depends on location The more distal to the Small Intestine the thicker and less frequent the output 53 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY COLOSTOMY Colorectal Cancer Diverticulitis Fecal Incontinence Trauma, blunt or penetrating Intestinal Obstruction, Volvulus, Intussusception Radiation Enteritis, damage during or following therapy 54 18 4/9/2014 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION End Loop Functional Stoma with Mucous Fistula ‐ Double Barrel Continent Stomas (with internal pouches) 55 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS END STOMA Proximal end of intestine brought up to abdominal wall, everted, and attached to skin Types of procedures for which End Stomas may be seen: Adominoperineal Resection – Removal of rectum, anus, and sphincter mechanisms Hartmann’s Procedure – Distal end of intestine closed, left in abdomen, may drain mucus/stool via rectum Total Proctocolectomy with Ileostomy – Removal of entire colon and rectum Abdominal (Subtotal) Colectomy – Portion of colon removed with rectal anastomosis, emergent procedure with toxic megacolon Restorative Proctocolectomy – Total colectomy, rectal excision and construction of an ileal reservoir with an ileoanal anastomosis 56 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION END STOMA 57 19 4/9/2014 SURGICAL PROCEDURES ADOMINOPERINEAL RESECTION PROCEDURE 58 SURGICAL PROCEDURES HARTMANN’S PROCEDURE 59 SURGICAL PROCEDURES TOTAL PROCTOCOLECTOMY WITH ILEOSTOMY 60 20 4/9/2014 SURGICAL PROCEDURES ABDOMINAL (SUBTOTAL) COLECTOMY 61 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION FUNCTIONAL STOMA WITH MUCOUS FISTULA Bowel severed, 2 ends brought through abdominal wall, 1 proximal and 1 distal Stapling devices have made these obsolete Distal end will drain mucous 62 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION FUNCTIONAL STOMA WITH MUCOUS FISTULA Indications: If Hartmann’s closure not done Distal un‐resectable obstruction 63 21 4/9/2014 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION FUNCTIONAL STOMA WITH MUCOUS FISTULA 64 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION DOUBLE‐BARREL 65 SURGICAL PROCEDURES TYPES OF STOMAS BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION KOCK POUCH – Continent Ileostomy 66 22 4/9/2014 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION LOOP STOMA Bowel brought through abdominal wall through transverse opening, everted, and matured. Rod placed under loop to prevent bowel from falling in to abdomen Created to protect a distal anastomosis or to manage a colonic obstruction Types of procedures for which Loop Stomas may be seen: Low Anterior Resection – mobilize rectum with anastomosis below peritoneal reflection with temporary ostomy Abdominal (Subtotal) Colectomy – Portion of colon removed with rectal anastomosis Restorative Proctocolectomy – Second stage procedure for UC or Crohn’s Transverse Loop Colostomy – May be emergent divergent procedure, e.g., obstructive distal carcinoma 67 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION LOOP STOMA 68 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION LOOP STOMA 69 23 4/9/2014 FECAL OSTOMIES AND STOMAS STOMA BASED UPON SURGICAL CONSTRUCTION LOOP STOMA Rod is typically removed by CWOCN on day 5 post‐op depending upon stoma evaluation/patient assessment 70 SURGICAL PROCEDURES RESTORATIVE PROCTOCOLECTOMY ILEOANAL ANASTOMOSIS (J POUCH) 71 SURGICAL PROCEDURES CONTRAINDICATIONS TO J POUCH Crohn’s Severely malnourished, toxic Cancer Obese Advanced age Incompetent anal sphincter 72 24 4/9/2014 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS NEPHROSTOMY Urinary Diversion Tube place in the kidney or bladder percutaneously 74 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY NEPHROSTOMY Urethral obstruction Kidney stone(s) Stricture Malignancy 75 25 4/9/2014 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS URETEROSTOMY Urinary Diversion Ureters mobilized and brought to skin surface Poor candidate for intestinal diversions 76 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY URETEROSTOMY Poor candidates for intestinal diversions Not a procedure of choice Lack of stoma creation Poor anatomic location High incidence of stenosis Temporary measure for pediatric patients 77 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS ILEAL CONDUIT Segment of small intestine utilized as conduit, proximal end closed, distal end brought out through opening in abdomen and used to create a stoma Ureters implanted in small intestine segment 78 26 4/9/2014 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY ILEAL CONDUIT Invasive bladder cancer Neurogenic bladder Congenital anomalies Refractory interstitial cystitis Patient unable to manage a continent urostomy or neobladder 79 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS CONTINENT URINARY DIVERSIONS Urinary reservoir created from isolated intestinal segments Reservoir anastomosed to the ureters Catheterizable stoma attached to the abdominal wall 80 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS INDIANA AND MIAMI POUCHES Continent Urostomy 81 27 4/9/2014 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY CONTINENT URINARY DIVERSIONS INDIANA POUCH AND MIAMI POUCH (gynecologic oncologic disease) Bladder cancer Neurogenic bladder Congenital anomalies/Epispadias Refractory interstitial cystitis Patient physically able to undergo a lengthy surgical procedure Adequate renal function 82 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS NEOBLADDER Reservoir made from detubularized intestine attached to the ureters Patient voids independently using native sphincter No stoma 83 URINARY OSTOMIES AND STOMAS INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY NEOBLADDER Cancer free trigone and urethra Competent unobstructed urethral sphincter 84 28 4/9/2014 SURGICAL PROCEDURES TRENDS Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Programs Restorative Proctocolectomy – Total colectomy, rectal excision and construction of an ileal reservoir with an ileoanal anastomosis Low Anterior Resection – mobilize rectum with anastomosis below peritoneal reflection with temporary ostomy Restorative Proctocolectomy – Second stage procedure for UC or Crohn’s Trends toward loop ileostomies for temporary diversion Less odor, decreases prolapse and herniation, lower morbidity rates Flexible rods – comfort Colorectal laparoscopic surgery common for stoma creation and expands surgical options Robotically-assisted surgery – Decreases OR time, blood loss, length of stay, complications, conversion rates, post-op pain, and cost 85 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT 3 PRIMARY PRINCIPLES: Maintain pouch seal for predictable consistent wear time Maintain peristomal skin integrity Support person with stoma (psychologically and physically) 87 29 4/9/2014 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN TO EACH PATIENT BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: Stoma characteristics Mucosa Protrusion Anatomic location Size and shape Lumen Stoma construction Stoma function/volume and consistency of effluent Peristomal skin integrity Peristomal plane characteristics Patient’s preferences and requirements 88 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: STOMA CHARACTERISTICS MUCOSA Normal: Red, moist, shiny, taut Edematous Shrinks in size up to 8 weeks after surgery No nerve endings Intact mucocutaneous junction Analogous to inside of cheek Abnormal: Grey, brown, black, flaccid Indicates impaired blood flow 89 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: STOMA CHARACTERISTICS PROTRUSION Ideally 1.0 to 1.5 cm above skin Flush stoma may require convexity Excessively long stoma may be injured ANATOMIC LOCATION Dictates selection of appliances Physical location on abdomen does not necessarily indicate anatomic origin, i.e., RLQ is always a ileostomy is not necessarily true 90 30 4/9/2014 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: STOMA CHARACTERISTICS SIZE AND SHAPE Depends upon reason for creation Type of stoma Surgical creation Round, oval, mushroom Measure stoma at longest and widest diameter STOMA LUMEN (OPENING) Dictates direction of flow of effluent Ideal lumen is straight up Lumen at skin level may require convexity, seal 91 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: STOMA FUNCTION/VOLUME AND CONSISTENCY OF EFFLUENT Depends on type and anatomic location Oral intake (solids and liquids) Medications Degree of ambulation Flatus expelled related to swallowed air and/or bacteria 92 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: PERISTOMAL SKIN INTEGRITY Normal: healthy and intact PERISTOMAL PLANE CHARACTERISTICS Refers to surface area located under skin barrier and adhesive of pouch system including area surrounding stoma Helps to determine shape, size, and construction of barrier required If possible, examine patient in supine, sitting, bending, and standing positions Examine skin firmness/softness around stoma 93 31 4/9/2014 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: PERISTOMAL PLANE CHARACTERISTICS 94 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: PERISTOMAL PLANE CHARACTERISTICS 95 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: PERISTOMAL PLANE CHARACTERISTICS 96 32 4/9/2014 PRINCIPLES OF STOMA MANAGEMENT INDIVIDUALIZED PLAN BASED UPON THE FOLLOWING: PATIENT’S PREFERENCES AND REQUIREMENTS Depends upon patient’s level of knowledge concerning procedure Patient’s ability and competence, e.g., visually impaired, mentally impaired, compromised dexterity Need for open‐end transparent pouch while in hospital Activities of daily living requirements 97 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES Type of Stoma: Primary Impact on Choice of Management System 99 33 4/9/2014 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES STANDARD OR EXTENDED WEAR BARRIERS The difference is how they interact with moisture and adhere to the skin Standard – Colostomy Extended Wear – Ileostomy and Urostomy SHAPE OF BARRIER Flat – Level skin contact area Convex – Outward curve that begins at aperture of skin barrier and extend outward KEY: Shape of skin barrier should be a mirror image of the topography of the peristomal plane 100 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES SKIN BARRIER SELECTION SKIN BARRIER MUST Provide predictable wear time (typically 4 days) Protect the peristomal skin SKIN BARRIER FUNCTION Protect peristomal skin from effluent Create a level pouch surface Solid and Paste skin barriers provide an adhesive seal Solid skin barriers may contain polymers, tackifiers, softeners, plasticizers, hydrocolloids, fillers, and pigment 101 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES SKIN BARRIER SELECTION 102 34 4/9/2014 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES POUCH SELECTION POUCH MUST Be emptied when 1/3 to 1/2 full Should be replaced after 2 days of wear if possible POUCH FUNCTION Contains stool/effluent/urine Odor control (filters available) 103 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES POUCH SELECTION TWO PIECE POUCH Available in many shapes, sizes, and configurations, open and closed end First considerations in choosing are length and film Choice of length depends on volume of stoma output and personal preference Film (transparent or opaque) Fabric or plastic backing – quiet (less crinkling) Skin barrier with flange, detachable pouch with access to stoma Low profile desired – minimal detection under clothes Pouch positioning on abdomen (oblique during hospital stay for emptying) Pouch Closure – Velcro like or tail closure Lifestyle friendly (versatile) Urostomy pouches have a tap (may be used for high output ileostomy patient) 104 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES POUCH SELECTION ONE PIECE POUCH Pouch with Barrier attached Very conformable Excellent option for the obese One‐step application Flexible Lightweight Flat or convex (integral) Used for situation where even the use of convexity may be difficult 105 35 4/9/2014 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES POUCH SELECTION TWO PIECE 106 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES POUCH SELECTION TWO PIECE OPTIONS SUR‐FIT Natura® Closed‐End Pouch with Filter SUR‐FIT Natura® Drainable Pouch with InvisiClose™ tail closure 107 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES POUCH SELECTION ONE PIECE 108 36 4/9/2014 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES ACCESSORIES EAKIN COHESIVE® SEALS 109 Eakin Cohesive is a registered trademark of T.G. Eakin Limited PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES ACCESSORIES NIGHT DRAINAGE SYSTEM 110 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES ACCESSORIES 3M™ Cavilon™ No Sting Barrier Film Pouch covers available 111 37 4/9/2014 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES USES OF CONVEXITY Flush stoma with effluent undermining barrier Location of stoma lumen at skin level Peristomal fistula Stoma retraction Abdominal creases, folds, and crevices, etc. 112 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES Flush, Retracted Stoma 113 PRODUCT SELECTION AND POUCHING PRINCIPLES GOALS FOR CONVEXITY To provide a mirror image of the skin around the stoma To maintain a secure seal between the pouch and the skin To obtain a predictable and sustained wear time To provide cost‐effective ostomy care To reduce the potential for complications To increase patient satisfaction 114 38 4/9/2014 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS GENERAL POINTS Occurs with almost every ostomate at some point Risk Factors Obesity Inflammatory Bowel Disease Stomas created in emergent situations 116 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS CANDIDIASIS Overgrowth of Candida organism causing inflammation, infection, or disease on peristomal skin May present as pustule which abrades upon removal of barrier adhesive, may see papules, erythema, maceration Patient complains of itching/burning Satellite lesions may be seen at edge of rash Generally limited to under adhesive seal (warm, dark environment) Risk Factors Antibiotics Surgery Moist environment (leakage) Diabetes Immunosuppressant drugs MANAGEMENT Identify and correct cause of moist environment, if cause Topical antifungal powder (Microguard Powder with 3M No‐Sting barrier film 117 (use crusting technique) 39 4/9/2014 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS Candidiasis 118 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS MUCOCUTANEOUS SEPARATION Detachment of stoma from skin at Mucocutaneous junction May result from poor healing, tension or superficial infection Risk Factors Diabetes Malnutrition Immunocompromised status Corticosteroids Infection Stoma necrosis Disease recurrence MANAGEMENT Assess peristomal junction by gently probing with Q‐Tip, determine depth and amount of circumference involved Determine tissue status (red – granular, yellow – fibrinous, black – necrotic) Separation filled with absorbent materials, i.e., hydrofibers Assess stoma frequently for changes, retraction/stenosis 119 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS Mucocutaneous Separation 120 40 4/9/2014 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS IRRITANT DERMATITIS Skin damage resulting from contact with fecal or urinary drainage or chemical preparations Skin damage located in sites exposed to stool, urine, or solvents Possibly from inadequate pouch seal, incorrect sizing, poor pouch technique, poor stoma location, prior peri‐stomal skin status Effluent destroys and erodes the epidermis Initially skin is red or with macular rash, may rapidly progress towards denudement Incidence varies 2.5% to 55% of ostomates MANAGEMENT Correct etiology Treat denuded skin – Stomahesive powder and 3M No‐Sting Barrier Film (Use crusting technique) Apply Triamcinolone Acetonide spray (Kenalog 60g), allow to dry, place Duoderm X‐tra Thin barrier around stoma prior to barrier and pouch application Prevention of reoccurrence through education 121 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS Irritant Dermatitis 122 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS RETRACTION Stoma protrusion disappearing to or below skin level Difficult to maintain seal Effluent may undermine Stoma may totally disappear from view when patient sits Risk Factors Obesity, short mesentery Excessive adhesions/scar Stoma length inadequacy, initially Improper skin excision Necrotic stoma Mucocutaneous Separation MANAGEMENT Convex pouching system with belt Referral to colorectal surgeon 123 41 4/9/2014 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS Retraction 124 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS UNDERMINING/LEAKAGE Effluent under barrier on peri‐stomal skin Use correct size ostomy barrier Always change barrier at the first sign of leakage Never patch barrier with tape or paste – Leaks need to be fixed! Empty pouch contents when 1/3 to no more than 1/2 full Use gas filter to release pressure Consult with CWOCN, pharmacist to learn about medications to reduce gas 125 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS Undermining 126 42 4/9/2014 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS PROLAPSE – LATE PRESENTATION Telescoping of bowel though the stoma, varies in length up to greater that 1 foot Incidence varies from 1 to 16%, usually occurs in loop stomas Risk Factors Obesity Increased intra‐abdominal pressure Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Bowel redundancy Weak fascia Technical factors that can lead to prolapsed stoma Improper stoma site outside the rectus muscle Oversized aperture Redundancy of the distal bowel at the stoma site MANAGEMENT Medical emergency requiring ED visit if stoma becomes in color and painful One piece flexible appliance 127 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS Prolapse 128 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS PARASTOMAL HERNIA Defect in fascia allowing loops of intestine to protrude into areas of weakness Appropriate stoma siting may minimize occurrence Presents as unsightly bulge either in one area or total area surrounding stoma with patient in sitting and/or standing position Patient may be insecure regarding pouch leaking Psychologically distressed regarding unsightly bulge Patient may complain of pain in the area of hernia MANAGEMENT Must wear one piece pouch system Hernia support belt/binder (Celebration, Nu‐Hope) must be measured Stool should be kept soft and pasty – prevent constipation Monitor color of stoma, if dark/dusky seek medical attention Schedule regular medical appointments, monitor hernia status 129 43 4/9/2014 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS Parastomal Hernia 130 STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS NECROSIS From impairment of blood flow through the stoma tissue resulting in stoma death Presents dark in color varying from maroon to black , flaccid to the touch Generally occurs within 24 hours after surgery May involve a portion, half, or all of the stoma above and below the fascia Reported incidence of early stoma necrosis ranges from 4.3% ‐ 17% Risk Factors High BMI (Body Mass Index) Short bowel Bowel edema These can increase mesenteric tension and consequently lack of blood flow MANAGEMENT Monitored with flashlight and lubricated pediatric test tube for viability One piece cut to fit transparent ostomy pouch only Can be a surgical emergency If blood flow is compromised at fascia level, patient must return to surgery for a 131 revision STOMA/PERI‐STOMAL COMPLICATIONS NECROSIS Necrotic Stoma 132 44 4/9/2014 PRE‐OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS PRE‐OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS PATIENT ASSESSMENT Medical and Surgical History Type of Surgical Procedure Scheduled Educational Level, Mental and Emotional Acuity Support System – Psychological and Social Support, Financial Issues Coping Styles Cultural and Spiritual Issues Sexuality Language Barriers Vision Hearing Hand Dexterity and Motor Skills Skin Sensitivity/Allergy Other Physical Challenges 134 STOMA SITE MARKING 45 4/9/2014 PRE‐OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS STOMA SITE MARKING Is a pre‐op activity performed by: Certified Wound Ostomy Continence Nurse (CWOCN) or Colorectal Surgeon Pre‐op teaching occurs during stoma‐siting 136 PRE‐OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS STOMA SITE MARKING WHY STOMA SITE? Patient needs to visualize stoma Assists surgeon with stoma placement Promote adequate appliance adhesion Prevent future stoma complications Opportunity for pre‐operative education 137 STOMA SITE MARKING One of the most important aspects of care provided by a WOC nurse Recommended by the American Society of Colorectal Surgeons (ASCS) A retrospective study of 1,616 medical records of persons who underwent ostomy surgery found that stoma site marking by a CWOCN decreased the incidence of stoma complications by half, suggesting that pre‐operative stoma site marking reduces the risk for developing ostomy complications A trained clinician can perform stoma site marking in the absence of a CWOCN or Colorectal Surgeon Should be provided for temporary or permanent stomas 138 46 4/9/2014 STOMA SITE MARKING PATIENT EXAMINED: Supine Sitting Bending /Standing LANDMARKS: Beltline Umbilicus Iliac crest Rectus muscle Infra‐umbilical bulge 139 STOMA SITE MARKING 140 STOMA SITE MARKING PLACEMENT: Within borders of rectus muscle on apex of infra‐umbilical bulge Avoid skin folds, deep creases, bony prominences, and beltline, if possible Location visible to patient Provision of 2.5 inches of adhesive surface for pouching system DOCUMENTATION: Patient in agreement with stoma site 141 47 4/9/2014 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES WHAT’S THIS? 143 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES POST‐OPERATIVE COMMUNICATION When communicating with stoma patients, you need to take account of both their practical and emotional needs Physical needs – how the stoma is managed Emotional needs – how the patient feels about their condition Consider how you would feel if you were told you had to wear a pouch on your abdomen to collect feces and how this would affect the way you thought about your body Sensitive communication includes: Using the right kind of language Being aware of your facial expressions/body language Dealing with a stoma is a very intimate and personal subject Listen to the patient and let them talk about their concerns and worries 144 48 4/9/2014 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES KEY POST‐OPERATIVE EDUCATION COMPONENTS In‐depth discussion of anatomy and physiology of the GI tract Technical aspects of ostomy management (demonstration and return demonstration recommended) Pouching system removal and application Pouch emptying and closure (demonstration and return demonstration recommended) Skin care Ostomy accessories Nutrition/medications Clothing Body image perception Psychological aspects Social/recreation Interpersonal relationships Sexual issues Intimacy issues Common complications/troubleshooting 145 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS CONSIDERATIONS Be sensitive to the religious and cultural issues which may affect the patient Ask for further information when you are unfamiliar with particular requirements There can be wide variety of different beliefs and practices How strictly practices are observed vary greatly, so it is important not to make assumptions Make sure you understand the needs of each patient as a unique individual In certain cultures, having a stoma may be regarded as “unclean”, adding to the difficulties for the patient in adjusting Ritual washing before prayer is required within some faiths, such as Islam or Hinduism Devout Muslims may be reluctant to use their right hand when cleaning their stoma (the right hand being used for eating, the left hand for cleaning and hygiene) Dietary requirements or the need for fasting can affect the frequency and consistency of the stoma output 146 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING Assess learner readiness (teach in small steps) Use of pouch clamp Looking at and measuring stoma Transferring measurement to the barrier (appropriate size selection or cut) Application of Eakin Seal around base of stoma, if indicated Placing barrier around base of stoma If two piece system, snapping pouch onto barrier Placing clamp on tail closure of pouch Emptying and rinsing pouches Peri‐stomal skin inspection 147 49 4/9/2014 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING KEY ISSUES Edema lasts up to 8 weeks Gas and odor Bathing and showering – with or without pouch (picture frame of tape) Clothing styles – no need to change unless stoma on higher plane Sexual function – pouch should be empty before activity, covers available Activities of daily living All activities acceptable, poly‐material caps available for boxing, etc Wear time: Average barrier wear time in US is 4.8 days Type of stoma and length of time since creation significantly affect wear time No significant relationship between geographic location, age, gender, or 148 BMI and wear time (skin condition – age) POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING DIET Use of gas filters, prevention of swallowing air, limit use of straws, refrain from smoking Frequent small meals Fecal Ostomy – Same foods caused gas pre‐op will cause gas post‐op: beans, onions, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, beer, eggs Ileostomy – Adequate fluid intake, must drink 8‐10 eight oz glasses of fluid per 24 hrs Must include fluids containing K+ and Na+ to prevent dehydration (Powerade, Gatorade, etc.; sugar‐free for diabetic patients ) Educate patient regarding foods that can increase consistency of fecal output, i.e., bananas, rice, pasta, cheese, applesauce, pretzels, white bread or toast, Rice Krispies Avoid high fiber foods, i.e., coconut, nuts, dried fruit, potato skins, Chinese food, stringy foods, celery 149 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING DIET (continued) Urostomates need to drink 2,000 – 2,500 ml of liquids a day to help prevent bacterial overgrowth and maintain urine pH in acidic range MEDICATIONS Most important consideration is length of small bowel for drug absorption Ileostomy patients May require antidiarrheals Loperamide (Imodium) dose for high output ileostomy: 4 mg twice a day for 4 days, then may increase to 12mg daily for 3 days Diphenoxylate (Lomotil) dose: 2 tables po 4x daily or 10ml solution po 4x daily, then decrease to amount necessary to maintain bowel movement Should never use laxatives Enteric coated medications not absorbed Colostomy patients develop constipation with calcium carbonate antacids/Ca+ 150 50 4/9/2014 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES IMPORTANT J POUCH POST‐OP CONSIDERATIONS High ileostomy output: 1,000 – 2,000+ ml/24 hours, illeostomy bypasses 20% or more of distal bowel leading to dehydration Inform Patient: Of signs and symptoms of dehydration To modify diet to include foods/liquids that will thicken stoma output To take anti‐diarrheal medications to slow output and encourage absorption Loop ileostomy (almost flush to skin) requires extended‐wear skin barrier and convex barriers are frequently necessary Educate patient regarding foods that can increase consistency of fecal output Bananas, rice, pasta, potato, noodles, cheese, applesauce, pretzels, white bread, Rice Krispies Inform patient that rectal pressure/fullness may be present, sitting on toilet expelling rectal contents is expected, mucous may be expelled 151 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING HEALTH RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE (HRQOL) – PATIENTS’ CONCERNS Impaired body image Fear of incontinence Fear of odor Limitations affecting: Social activities Travel‐related activities Leisure activities Impaired sexual function HRQOL significantly highest among patients satisfied with their care and when they ranked the ostomy nurse as having a genuine interest in them as individuals 3 longitudinal studies demonstrate HRQOL rises steadily during first post‐op year, especially among young adults Greatest rise in HRQOL occurs between the immediate post‐op period and the 3rd post‐op month and gradually improves over the 1st post‐op year 152 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING OTHER FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE HRQOL Underlying reason for the ostomy Presence and severity of ostomy complications Presence and severity of comorbid conditions Sexual function Age Ability to pay for ostomy supplies SUPPORT GROUPS National: United Ostomy Association of America (UOAA) Local: Broward Health Coral Springs “Caring and Sharing” Broward Ostomy Association (BOA) OUTPATIENT CENTER Broward Health Coral Springs 153 51 4/9/2014 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING OTHER RESOURCES American Cancer Society at www.cancer.org Broward Ostomy Association at www.browardostomy.org C3Life Community Connection Center at www.c3life.com Crohn's Colitis Foundation of America CCFA at www.ccfa.org Friends of Ostomates Worldwide at www.fowusa.org Gay & Lesbian Ostomates at www.glo‐uoaa.org Great Comebacks at www.greatcomebacks.com International Ostomy Association at www.ostomyinternational.org United Ostomy Associations of America at www.uoaa.org Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses Society at www.wocn.org 154 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING MANUFACTURER LINKS Bag It Away Ostomy Disposal Bags at http://bagitaway.com Celebration Ostomy Support Belt at www.celebrationostomysupportbelt.com Coloplast at www.coloplast.com ConvaTec at www.convatec.com Cymed Incorporated at www.cymed‐ostomy.com Hollister Incorporated at http://hollister.com Marlen Manufacturing & Development Company at www.marlenmfg.com Nu‐Hope Laboratories at www.nu‐hope.com Osto‐EZ‐Vent at www.kemonline.com Parthenon at www.parthenoninc.com Smith & Nephew Inc. at www.smith‐nephew.com Sto Med Inc. at www.sto‐med.com 155 POST‐OPERATIVE ACTIVITIES TEACHING TROUBLESHOOTING ASSISTANCE Refer to written and pictorial educational material Utilize provided home healthcare nurse Contact CWOCN Contact Colorectal Surgeon Refer to provided lists of resources Support Groups Websites Organizations Contact manufacturers Refer to mental health provider if indicated 156 52 4/9/2014 REFERENCES: Abdominoperineal Resection.html. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.georgiahealth.edu/medicine/surgery/midds/patient_education/abdominoperineal_resection.html Abraham, N. (2011). Enhanced recovery after surgery programs hasten recovery after colorectal resections. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 3(1), 1. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v3.i1.1 Abraham, N. (n.d.). Peri‐Operative Care in Colorectal Surgery in the Twenty‐First Century. Retrieved from http://cdn.intechweb.org/pdfs/28755.pdf Allen‐Mersh, T. G., & Thomson, J. P. (1988). Surgical treatment of colostomy complications. The British journal of surgery, 75(5), 416–418. ASCRS and WOCN Joint Position Statement on the Value of Preoperative Stoma Marking for Patients Undergoing Fecal Ostomy Surgery, J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2007; 34 (6): 627‐628. Bak, G. P. (n.d.). Teaching ostomy patients to regain their independence. Retrieved from http://woundcareadvisor.com/wp‐ content/uploads/2012/10/Ostomy_S‐O12.pdf Binns, J. C., & Isaacson, P. (1978). Age‐related changes in the colonic blood supply: their relevance to ischaemic colitis. Gut, 19(5), 384–390. Butler, D. L. (2009). Early postoperative complications following ostomy surgery: a review. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 36(5), 513–519. Clearinghouse, T. N. N. D. D. I. (n.d.). Fecal Incontinence. text. Retrieved from http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/fecalincontinence/#what Colonic Volvulus. (n.d.). Retrieved, from http://www.fascrs.org/physicians/education/core_subjects/2012/colonic_volvulus/ Colorectal Surgery Enhanced Recovery Programme ‐ Draft Guidelines. (n.d.). Retrieved, from http://www.slideshare.net/fast.track/colorectal‐surgery‐enhanced‐recovery‐programme‐draft‐guidelines 157 REFERENCES (CONTINUED): Colostomy Guide.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.unchealthcare.org/site/Nursing/servicelines/wocn/patient%20educational%20materials_new/Colostomy%20G uide Colwell JC, Goldberg MT, Carmel JE. In Fecal and Urinary Diversions, Management Principles. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004 104‐ 105, 217‐229. Colwell JC, Gray M. Does Preoperative Teaching and Stoma Site Marking Affect Surgical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Ostomy Surgery? J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2007; 34 (5): 492‐496. consensus‐review‐of‐optimal‐perioperative‐care.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://scoap.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/consensus‐review‐of‐optimal‐perioperative‐care.pdf DescriptionofOstomySurgeries.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://my.clevelandclinic.org/Documents/Digestive_Disease/DescriptionofOstomySurgeries.pdf dietary‐strategies‐for‐fecal‐incontinence.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://my.clevelandclinic.org/Documents/Digestive_Disease/woc‐spring‐symposium‐2013/dietary‐strategies‐for‐fecal‐ incontinence.pdf Diverticulitis. (2013). Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/173388‐overview#aw2aab6b2b4aa Doughty, D. B. (2008). History of ostomy surgery. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 35(1), 34–38. Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116:544–573. 158 REFERENCES (CONTINUED): ERAS program for colorectal surgery. (n.d.). Retrieved, from https://www.google.com/search?q=eras+program+for+colorectal+surgery&ie=utf‐8&oe=utf‐8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en‐ US:official&client=firefox‐a#q=eras+program+for+colorectal+surgery&client=firefox‐a&rls=org.mozilla:en‐ US:official&ei=hYuWUbeZCZPK9QTd7IHgBw&start=20&sa=N&bav=on.2,or.r_qf.&bvm=bv.46751780,d.eWU&fp=9deb35a48 64e0689&biw=1360&bih=677 Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. (2012). Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/175377‐overview fecal‐incontinence‐treatment‐options.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://my.clevelandclinic.org/Documents/Digestive_Disease/woc‐spring‐symposium‐2013/fecal‐incontinence‐treatment‐ options.pdf Gandhi, S. K., Hanson, M. M., Vernava, A. M., Kaminski, D. L., & Longo, W. E. (1996). Ischemic colitis. Diseases of the colon and rectum, 39(1), 88–100. Gervaz, P., Morel, P., & Vozenin‐Brotons, M.‐C. (2009). Molecular Aspects of Intestinal Radiation‐Induced Fibrosis. Current Molecular Medicine, 9(3), 273–280. doi:10.2174/156652409787847164 Green, B. T., & Tendler, D. A. (2005). Ischemic colitis: a clinical review. Southern medical journal, 98(2), 217–222. Green, N., Iba, G., & Smith, W. R. (1975). Measures to minimize small intestine injury in the irradiated pelvis. Cancer, 35(6), 1633–1640. Gustafsson, U. O., Scott, M. J., Schwenk, W., Demartines, N., Roulin, D., Francis, N., … Ljungqvist, O. (2012). Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Colonic Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society Recommendations. World Journal of Surgery, 37(2), 259–284. doi:10.1007/s00268‐012‐1772‐0 Hass, D. J., Kozuch, P., & Brandt, L. J. (2007). Pharmacologically mediated colon ischemia. The American journal of gastroenterology, 102(8), 1765–1780. doi:10.1111/j.1572‐0241.2007.01260.x Hoentjen F, Colwell JC, Hanauer SB, Complications of Peristomal Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease, A Case Report and Review of Literature, J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012; 39 (3): 297‐301. 159 53 4/9/2014 REFERENCES (CONTINUED): Howlander N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. Seer Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2008. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011. Based on November 2010 seer data submission. Gastinger I, Marusch F, Steinert R, Wolff S, Koeckerling F, Lippert H. Protective defunctioning stoma in low anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1137–1142. Husain, S., & Cataldo, T. (2008). Late Stomal Complications. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 21(1), 031–040. doi:10.1055/s‐2008‐1055319 Intestinal Radiation Injury. (2013). Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/180084‐overview Johns Hopkins Colon Cancer Center, Colorectal Cancer Overview. (n.d.). From http://www.hopkinscoloncancercenter.org/CMS/CMS_Page.aspx?CurrentUDV=59&CMS_Page_ID=D291D721‐32CD‐4CD7‐ B607‐3B5B3BC2893C Molodecky NA, Shiansoon I, et al., Increasing Incidence and Prevalence of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease with Time, Based on Systematic Review, Gastroenterology. 2012; 142 (1): 46‐54 e42. Kann, B. (2008). Early Stomal Complications. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 21(1), 023–030. doi:10.1055/s‐2008‐ 1055318 Kim, J. T., & Kumar, R. R. (2006). Reoperation for Stoma‐Related Complications. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 19(4), 207–212. doi:10.1055/s‐2006‐956441 Lassen, K., Soop, M., Nygren, J., Cox, P. B. W., Hendry, P. O., Spies, C., … Norderval, S. (2009). Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Archives of Surgery, 144(10), 961. management‐IAD.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://my.clevelandclinic.org/Documents/Digestive_Disease/woc‐spring‐ symposium‐2013/management‐IAD.pdf Memorial Sloan‐Kettering Cancer Center Certified Wound, Ostomy, & Continence Nurses (2009) Colostomy and Ileostomy: Common Questions, Patient Information Booklet, Memorial Sloan‐Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 160 REFERENCES (CONTINUED): National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Bladder Cancer. Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). (n.d.). Management of the patient with a fecal ostomy: best practice guideline for clinicians. From http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=23869 Nygren, J., Thacker, J., Carli, F., Fearon, K. C. H., Norderval, S., Lobo, D. N., … Ramirez, J. (2012). Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Rectal/Pelvic Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society Recommendations. World Journal of Surgery, 37(2), 285–305. doi:10.1007/s00268‐012‐1787‐6 osted_undost_eng_single.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.hollister.com/us/files/pdfs/osted_undost_eng_single.pdf Ostomies and Stomal Therapy. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.fascrs.org/physicians/education/core_subjects/1998/ostomies_and_stomal_therapy/ Pittman J, Characteristics of the Patient with an Ostomy, J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2011; 38 (3): 271‐279. RCS‐fecal‐management‐systems‐and‐anal‐erosion.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://my.clevelandclinic.org/Documents/Digestive_Disease/woc‐spring‐symposium‐2013/RCS‐fecal‐management‐systems‐ and‐anal‐erosion.pdf Richbourg L, Fellows J, Arroyave WD, Ostomy Pouch Wear Time in the United States, J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008; 35 (5): 504‐508. Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Kuchler T, Longo WE, Kremer B. Prospective evaluation of quality of life of patients receiving either abdominoperineal resection or sphincter‐preserving procedure for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:117–123. SecuriCare (Medical) Ltd (2008) Stoma Care for Health Care Assistants, SecuriCare (Medical) Ltd, High Wycombe, UK Strate, L. L., Liu, Y. L., Aldoori, W. H., Syngal, S., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2009). Obesity Increases the Risks of Diverticulitis and Diverticular Bleeding. Gastroenterology, 136(1), 115–122.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.025 161 REFERENCES (CONTINUED): Sun, V., Grant, M., McMullen, C. K., Altschuler, A., Mohler, M. J., Hornbrook, M. C., … Krouse, R. S. (2013). Surviving Colorectal Cancer: Long‐term, Persistent Ostomy‐Specific Concerns and Adaptations. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 40(1). Teeuwen, P. H. E., Bleichrodt, R. P., Strik, C., Groenewoud, J. J. M., Brinkert, W., Laarhoven, C. J. H. M., … Bremers, A. J. A. (2009). Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Versus Conventional Postoperative Care in Colorectal Surgery. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 14(1), 88–95. doi:10.1007/s11605‐009‐1037‐x Theodoropoulou, ?ngeliki, & ?outroubakis, I. E. (2008a). Ischemic colitis: Clinical practice in diagnosis and treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 14(48), 7302–7308. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.7302 Theodoropoulou, A. & Koutroubakis, I. E. (2008). Ischemic colitis: Clinical practice in diagnosis and treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 14(48), 7302–7308. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.7302 U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2009 Incidence and Mortality Web‐based Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2013. Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs Willett, C. G., Ooi, C.‐J., Zietman, A. L., Menon, V., Goldberg, S., Sands, B. E., & Podolsky, D. K. (2000). Acute and late toxicity of patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing irradiation for abdominal and pelvic neoplasms. International Journal of Radiation Oncology * Biology * Physics, 46(4), 995–998. Worth C, Peristomal Skin and Ostomy Care, Ostomy Wound Management, 2011; Oct: 8. 2008 and 2009 Colandar (calendars). The Colon Club, 17 Peach Tree Lane, Wilton, NY 12831 (2003). Principals of Stoma Siting [Video]. American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) Foundation, 85 W. Algonquin Rd., Suite 550, Arlington Heights, IL 60005 162 54