Stoma Complications: Best Practice for Clinicians

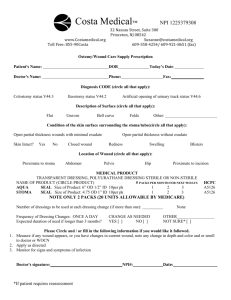

advertisement

Stoma Complications: Best Practice for Clinicians Stoma Complications: Best Practice for Clinicians The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society™ suggests the following format for bibliographic citations: Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. (2014). Stoma Complications: Best Practice for Clinicians. Mt. Laurel: NJ. Author. Copyright© 2014 by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society™ (WOCN®). Date of Publication: 11/26/2014. No part of this publication may be reproduced, photocopied, or republished in any form, in whole or in part, without written permission of the WOCN Society. WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 2 Acknowledgments Stoma Complications: Best Practice for Clinicians This document was developed and completed by the WOCN Society’s Clinical Practice Ostomy Committee in August 2013. Shirley Sheppard, Chair, MSN, CWON Certified Wound Ostomy Nurse University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System Chicago, IL Jacqueline Perkins, MSN, ARNP, CWOCN, FNP Wound Ostomy Nurse Practitioner VA Central Iowa Health Care Des Moines, IA Carole A. Bauer, MSN, CWOCN, OCN Advanced Nursing Practice Karmanos Cancer Center Detroit, MI Anita Prinz, MSN, CWOCN, CFCN Consulting Holistic Ostomy and Wound Care Boynton Beach, FL Nina Blanton, CWOCN Clinical Nurse Specialist Palmetto Health Baptist Columbia, SC Michelle Rice, BSN, CWOCN Ostomy Clinical Nurse Specialist Duke University Hospital Durham, NC Joanne Burgess, BSN, CWOCN Wound Ostomy Continence Nurse WakeMed Health and Hospitals Cary, NC Christine Sterneckert, BSN, CWOCN Consulting and Patient Care Primary Children’s Medical Center Salt Lake City, UT Mary Mahoney, MSN, CWON Certified Wound Ostomy Nurse UnityPoint at Home Urbandale, IA Carla VanDyke, CWOCN Clinical Nurse Specialist Presbyterian Healthcare Services Albuquerque, NM Janet Mantel, MA, RNC, CWOCN Certified Wound Ostomy Continence Nurse Englewood Hospital and Medical Center Englewood, NJ WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 3 Introduction and Purpose Ideally, a stoma should appear red or pink, moist, and slightly elevated from the surrounding skin. There may be underlying conditions that predispose certain individuals to stomal complications. The seven most common stomal complications described in the literature are hernia, laceration, mucocutaneous separation, necrosis, prolapse, retraction, and stenosis. This document was originally developed by the WOCN® Society’s Clinical Practice Ostomy Committee as a best practice guide for clinicians who care for patients with ostomies (Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society [WOCN], 2005). The purpose of this updated document is to facilitate the identification, assessment and management of common stomal complications. This document does not include common peristomal skin conditions related to pouching problems. For each of the seven common complications, this best practice guide provides an overview with a description and information about assessment and nursing interventions. The following information is provided for each complication: definition, contributing factors/risks, potential complications, identifying characteristics, assessment parameters; and nursing interventions for prevention, management, patient/caregiver education, and indications for referral to a primary healthcare provider. Also, recommendations for further research to expand the evidence-base about stomal complications and their management are provided. Please see the appendix (Figures 1-7) for images of the seven stomal complications (WOCN, 2007a). WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 4 PERISTOMAL HERNIA Assessment Definition Identifying characteristics • A peristomal hernia is a bulge under the peristomal skin • A bulge is noticeable around the stoma. o The bulge can vary in size and it may be partial or indicating that one or more loops of bowel have passed circumferential. through the dissected area of fascia and muscle, which was needed to externalize the stoma; and the bowel is • The bulge may reduce in size when the patient lies now protruding into the subcutaneous tissue around the down and increase in size when the patient stands, sits, stoma (Thompson, 2008; WOCN, 2010, 2011). or exerts him/herself. o It affects up to 50% of patients within one year • The stoma may also change in size or shape. following creation of the stoma (WOCN, 2011). • A hernia is often asymptomatic, or it can be o It may be associated with a prolapsed stoma (Husain symptomatic with pain, bulging, and poor fit of the & Cataldo, 2008). pouch (Bafford & Irani, 2013). o Recurrence is common (Husain & Cataldo, 2008): • Subclinical hernia: If the patient's history suggests a 50-100% after local fascial repair. hernia but the physical exam does not indicate a hernia 4-44% after local laparoscopic fascial repair with is present, then further testing may be indicated. A cat mesh. scan with oral contrast or an upper GI x-ray such as a 68% after stoma relocation/translocation. small bowel series or retrograde contrast study to visualize the loops of bowel may help determine if a hernia is present. Description Nursing Intervention Prevention • Marking the stomal site within the rectus muscle may reduce the risk of a hernia developing (WOCN, 2011). • Patients should: o Lose excess weight prior to surgery (WOCN, 2011). o Attain/maintain their waistline at less than 39.4 inches or 100 cm (De Raet, Delvaux, Haentjens, & Van Nieuwenhove, 2008). o Avoid lifting over 5 pounds for 6 to 8 weeks after surgery. o Stop smoking (Arumugam et al., 2003). o Use abdominal support belts and garments when doing heavy lifting or heavy work (WOCN, 2011). o Support the abdominal area with a pillow or hands when coughing or sneezing during the post-operative period. o Abstain from active abdominal exercises or lifting heavy objects for at least 3 months following surgery (WOCN, 2011). o Maintain adequate postoperative nutrition (WOCN, 2011). Contributing factors/risks Assessment parameters Management • An aperture/opening through the abdominal muscle that • Assess for the following symptoms or problems: • Modify the pouching system if needed: strategies to o Abdominal pain. is too large (WOCN, 2011; 2010). consider include: o A one-piece flexible system. o Bowel obstruction. • Obesity (Husain & Cataldo, 2008; WOCN, 2010, o A two-piece system with a floating flange. o Change in bowel habits. 2011). o A two-piece flexible or flangeless system. o Difficulty with the colostomy irrigation that was not • Older age (Husain & Cataldo, 2008; WOCN, 2010, o Cautious use of tape to avoid shear. present prior to the hernia. 2011). o Cautious use of convexity to avoid pressure. o Signs of ischemic bowel. • Weakness of the abdominal musculature (WOCN, o Adjusting the size and shape of the opening in the • Monitor the skin for pressure areas from the pouching 2010, 20101). skin barrier/wafer as needed. system. • Location of the stoma outside the rectus muscle • If condition allows, measure the patient for a hernia • Ask the patient if the wear time of the pouching system (Husain & Cataldo, 2008; Thompson, 2008; WOCN, support belt per manufacturer’s instructions, and apply has changed. 2010, 2011). the belt with the patient in a supine/flat position. • Observe for leakage and peristomal skin irritation. • Waist circumference greater than 39.4 inches or 100 • Use caution when irrigating a colostomy in a patient • Remove the ostomy pouch and observe for a bulge centimeters (De Raet et al., 2008). who has a parastomal hernia, and use only a conearound the stoma when the patient performs the • Wound infection (WOCN, 2010). tipped irrigator to reduce any risk of perforation (Grant Valsalva maneuver while standing and in a supine • Excessive coughing and vomiting after surgery that et al., 2012; Varma, 2009; Williams, 2011). position (WOCN, 2011). causes increased abdominal pressure (Bafford & Irani, o Some experts consider a parastomal hernia as a o While the patient performs the Valsalva maneuver, 2013; WOCN, 2011). contraindication to colostomy irrigation (Carlsson et gently perform a digital examination of the stoma to • Stomal construction such as a double-barrel stoma or al., 2010; Hatton & Brierley, 2011; Perston, 2010). identify the fascial defect and bowel loop (WOCN, loop colostomy (WOCN, 2011). 2011). WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 5 Description • Laparascopic technique for colorectal surgery where the stoma is brought out through the same incision used to remove the resected specimen (Randall, Lord, Fulham, & Soin, 2012). • Intra-abdominal tumor growth (WOCN, 2010, 2011). • Pregnancy, if accompanied by excessive vomiting (WOCN, 2010, 2011). • Smoking tobacco (WOCN, 2010). • Steroid use (Husain & Cataldo, 2008; WOCN, 2010, 2011). • Emergency stoma placement or prior stoma placement (WOCN, 2011). Potential complications • Stomal and peristomal changes that may cause leakage of the pouching system and peristomal skin irritation. • Mucosal stretching/spreading (WOCN, 2011). • Incarceration, strangulation, perforation and complete obstruction, which are the most dangerous complications of a hernia and require emergency surgery (Bafford & Irani, 2013; De Raet et al., 2008; Heo et al., 2011; WOCN, 2011). PERISTOMAL HERNIA Assessment Nursing Intervention Patient/caregiving education • Teach the patient to: o Perform skin care and pouching procedures. o Apply the support belt while lying down in a reclining, flat position. o Wear the support belt while up and ambulatory, and remove it while in bed. o Measure the stoma periodically and adjust the size of the opening in the skin barrier/wafer as needed. o Use only a cone-tipped irrigator for colostomy irrigations. If patients have trouble instilling water during colostomy irrigations or poor returns, they should stop the irrigations. If the colostomy irrigation is stopped, the patient may need a mild laxative and stool softeners or dietary modifications to promote bowel regularity. Reassure the patient that the stoma should continue to function without difficulty. o Call their healthcare provider or ostomy nurse, or seek emergency care if signs and symptoms of blockage, obstruction, incarceration or strangulation occur, such as (WOCN, 2011): Decreased output. Pain. Abdominal cramping. Distension around the stoma. Nausea and emesis (Kann, 2008). Dusky, black or necrotic color of the stoma (Shabbir & Britton, 2010). WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 6 Description PERISTOMAL HERNIA Assessment Nursing Intervention • If they are medically able, encourage patients to exercise regularly to maintain abdominal muscle tone and strength. Refer to the primary healthcare provider • Persistent peristomal skin irritation. • Recurrent pouching difficulties. • Signs and symptoms of incarceration and reduced blood flow to the stoma (e.g., stoma turns gray, dark or black), which indicates that the patient needs immediate medical/surgical attention (WOCN, 2011). WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 7 Description Definition • A stomal laceration is a cut or tear that most often develops as a result of the pouching technique (e.g., stoma rubbing against part of the pouching system) (Ratliff, Scarano, Donovan, & Colwell, 2005). • Lacerations may also develop in conjunction with trauma (e.g., car accident, shaving with a razor). Contributing factors/risks • Misalignment of the pouching system. • A peristomal hernia. • Stomal prolapse. LACERATION Assessment Identifying characteristics • The stoma’s mucosa presents with a yellow to white linear discoloration. • There is usually no pain associated with a laceration, and bleeding may or may not be present. • Lacerations usually heal when the causative factor is removed. Assessment parameters • Assess the patient’s technique for applying the pouching system. o Examine the stoma while the pouching system is in place to check for proper fit and alignment of the skin barrier/wafer. o Assess if belts or clothing are causing an improper fit. o Remove the skin barrier/wafer and assess for proper fit. • Rule out other stomal complications, such as Crohn’s ulcer, malignant lesion, or diverticulosis. Nursing Intervention Prevention • Cautiously clip or shave hair in the direction away from the stoma to avoid cutting the stoma. • Consider using a rigid, protective, dome cover over the stoma during activities that have a potential for forceful injuries, such as contact sports or physical labor. Management • Eliminate the factor(s) that caused the laceration. • Resize the pouching system or the skin barrier/wafer so that the stoma is not in contact with the flange or other firm edges. • Adjust tight clothing that may be impinging on the stoma. • Use hemostatic measures as needed to control bleeding (e.g., silver nitrate, which may require an order from the primary health care provider). Patient/caregiver education • Encourage the patient to follow preventive measures. • Teach the patient: o That blood in the pouch may be a sign of a laceration. o To apply direct pressure to stop excess bleeding. o Seek urgent medical assistance if bleeding does not stop. o Skin care and pouching procedures. Refer to the primary healthcare provider • Lacerations that do not heal. • Uncontrolled or repeated bleeding. • Severed stoma. Potential complications • Excessive bleeding. • Compromised functioning of stoma which could require emergent surgery. • Severed stoma. WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 8 MUCOCUTANEOUS SEPARATION Description Assessment Definition Identifying characteristics • A mucocutaneous separation occurs when a stoma • With a mucocutaneous separation, there is an completely or partially separates/detaches from the skin observable separation between the stoma and skin. (Butler, 2009). • The separation may be preceded by erythema, a darker o It can be superficial or deep. discoloration, or induration at the mucocutaneous junction with absence of a ridge adjacent to the mucosal-dermal junction. Contributing factors/risks Assessment parameters • Conditions that compromise wound healing (Boyd• Describe the location/extent of the separation. o The location of a separation is often described by Carson, Thompson, & Boyd, 2004; Butler, 2009): o Abdominal radiation. referring to the stoma as the face of a clock (e.g., o Corticosteroid use. mucocutaneous separation present from the 1 o’clock o Diabetes. to 3 o’clock position). o Infection. o Identify the depth of the separation in centimeters. o Malnutrition (Butler, 2009). Gently measure the depth with a cotton-tipped o Smoking (Franz et al., 2008). applicator. o Irritable bowel disease (Boyd-Carson et al., 2004). Do not force the cotton-tipped applicator into the o Chemotherapy (Boyd-Carson et al., 2004). defect. o Fecal contamination at the suture line (Boyd-Carson If you are unfamiliar with this procedure, refer the et al., 2004). patient to a surgeon for further evaluation. • Additional contributing factors/risks include: • Identify if slough is present (Butler, 2009). o An abdominal wall opening that is larger than the • Assess if pain is present, which could indicate an bowel. underlying disease process, and may help determine o Excessive tension on the suture line. the extent of the separation. o Stomal necrosis. • Assess for a fistula if fecal material is in the separation o Convexity, which may cause deeper tissue destruction (Butler, 2009). and impaired healing at the stoma/skin junction • Assess the amount of drainage from the site, which (WOCN, 2007b). varies and might require more frequent pouch changes. Potential complications • Infection (Boyd-Carson et al., 2004; Butler, 2009). • Peritonitis (Bafford & Irani, 2013). • Stomal stenosis (Butler, 2009). • Stomal retraction (Bafford & Irani, 2013). Nursing Intervention Prevention • If possible, avoid early use of convexity (Rolstad & Beaves, 2006). • Seek a preoperative nutritional consult, as needed (Fulham, 2008). • Encourage pre-op and post-op smoking cessation (Franz et al., 2008). Management • Flush the separated area with normal saline, tap water, or a noncytotoxic wound cleanser. • Fill the separation with a product to absorb drainage and provide an environment for healing. o Product selection may vary according to the depth and amount of drainage (e.g., skin barrier paste, skin barrier powder, calcium alginates, hydrofiber). o After the defect is filled, apply the pouching system over the separation, exposing only the stoma. • Consider using a two-piece system with an easy-to remove pouch (e.g., flangeless or floating flange) to facilitate patient comfort during pouch removal and reapplication. • Change the pouching system more frequently if needed to provide wound care to the separation: o If wound care is needed daily or more often, consider using a pouching system that allows access to the separation, so the system does not have to be changed with each treatment (e.g., two-piece system or wound drainage collector). Patient/caregiver education • Teach the patient care of the mucocutaneous separation and pouching procedures. Refer to the primary healthcare provider • Any separation that is suspected to extend below the level of the fascia, which warrants referral to a surgeon. WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 9 NECROSIS Description Definition • Necrosis is tissue death that occurs when blood flow to or from a stoma is impaired or interrupted. Contributing factors/risks • Edema of the bowel wall. • Embolism/arterial compromise (Kann, 2008). • Extensive stripping of/or tension on the mesentery. • Hypotension/hypovolemia. • Obesity. • Sutures that are placed too close together or are too tight. • Constriction from a skin barrier/wafer opening that is too small (Butler, 2009). • Abdominal edema or distension (Butler, 2009). Assessment Identifying characteristics • With necrosis, the stoma may be dark red, purplish, dusky blue (cyanotic tint), gray, brown, or black. • The mucosa may be soft and flaccid (Butler, 2009), or it might be hard and dry. • Necrosis is most likely to occur within the first 5 postoperative days. • Necrosis often occurs within 24 hours of the surgery (Butler, 2009; Colwell, Goldberg, & Carmel, 2004). • The necrosis can involve the entire stoma or affect only scattered areas, and it may be superficial or deep. Assessment parameters • Assess the color of the stoma and mucosal appearance every 8 hours for the first 72 hours after surgery. Notify surgeon if color is not red/pink. • Monitor the stoma for progression of the necrosis and for sloughing of the tissue. o The necrotic tissue may cause an offensive odor. • Consider assessing the level of necrosis/viability of the stoma by gently inserting a clear, well-lubricated glass tube into the stoma and visualizing the lumen of the stoma using a penlight (Butler, 2009; Colwell et al., 2004; Kann, 2008). o When the light is shined into the tube, viable mucosa appears red and healthy (Kann, 2008). • Assess if the suture line is intact during changes of the pouching system. • Rule out melanosis coli, a condition in which the stoma is brownish black due to excessive use of an anthraquinone laxative such as cascara (McQuaid, 2012). Potential complications • Mucocutaneous separation. • Peritonitis. • Stomal retraction. • Stomal stenosis. Nursing Intervention Prevention • Monitor for increased edema and enlarge the stomal opening of the pouching system, as needed, to prevent constriction of the stoma. • Assess for and recommend measures to manage abdominal distension as needed (e.g., nasogastric tube). • Assess for and recommend measures to manage hypovolemia and hypotension (Butler, 2009). Management • Use a transparent pouch to visualize the stoma. • Use a two-piece pouching system, so the pouch can be removed as needed for close inspection of the stoma. • Size the opening of the pouching system to prevent constriction of the stoma. • Resize the pouching system as nonviable tissue sloughs and the stomal opening contracts. • Monitor for stenosis. Patient/caregiver education • Prepare the patient for anticipated changes in the stoma (e.g., color changes, tissue sloughing). • Encourage the patient to observe the appearance of the stoma on a daily basis, and to use a transparent pouch. Refer to the primary healthcare provider • Necrosis that extends beyond the level of the fascia, which requires surgical intervention. WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 10 PROLAPSE Description Assessment Definition Identifying characteristics • A prolapse occurs when a full thickness length of bowel • The prolapsed bowel varies in length (e.g., 5-13 protrudes through an ostomy (Bafford & Irani, 2013; inches), becomes edematous from the dependent Butler, 2009). position, is prone to bleed, and is at risk of trauma (Butler, 2009). • Loop colostomies prolapse more often than end • The patient may not experience any pain or obstruction colostomies (Bafford & Irani, 2013). o Prolapse occurs in 2-22% of loop ostomies (Maeda et with the prolapse (Husain & Cataldo, 2008). al., 2003). o Prolapses of transverse loop colostomies are the most common, but prolapses can be seen with any stoma (Husain & Cataldo, 2008). • Classification of prolapsed stomas (Bafford & Irani, 2013): o Fixed: Permanent eversion of an excessive length of bowel. o Sliding: Intermittent protrusion of bowel through the stomal orifice, usually because of an increase in intraabdominal pressure, such as during the Valsalva maneuver. Contributing factors/risks Assessment parameters • An abdominal wall opening that is larger than the • Assess: o Presence of pain: A prolapse is usually painless bowel. (Husain & Cataldo, 2008). • Inadequate fixation of the bowel to the abdominal wall. o The stomal mucosa for trauma and laceration (Black, • Increased abdominal pressure associated with tumors, 2009). coughing, or an infant’s crying. Infants are at risk due to o The fit of the pouching system. abdominal pressure while crying. o The peristomal skin. • Lack of fascial support such as with infants, adults after o The viability of the stoma: Compromised circulation multiple abdominal surgeries, or patients of advanced may manifest as a dusky, purple, dark black, or very age (Bafford & Irani, 2013). pale stoma. • Obesity. o Presence of a peristomal hernia, which might be • Pregnancy. associated with a prolapsed colostomy. • Weak abdominal muscle tone. o Signs/symptoms of obstruction, incarceration, or strangulation, which are absolute indications for • Emergency surgery, which might result in: surgical intervention/repair. o A stoma that is not created through the rectus muscle. o A large opening in the abdominal wall to accommodate an intestine that is edematous at the time of surgery (Husain & Cataldo, 2008). WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 11 Nursing Intervention Prevention • If circumstances permit, for obese patients encourage weight loss prior to surgery and long-term weight management after surgery. • Encourage patients who are medically able to exercise regularly to maintain abdominal muscle tone and strength. Management • With the patient in a reclining position, attempt to manually reduce the prolapse by applying gentle continuous pressure to the distal portion of the stoma. • Manual reduction of an edematous, prolapsed stoma may be enhanced by temporarily decreasing the edema with an application of cold compresses or sugar to the prolapse for 10-15 minutes (Butler, 2009; Husain & Cataldo, 2008). • Apply a support binder or an ostomy/hernia support belt with a prolapse overbelt. o The belt must be applied while the prolapse is reduced, which is best accomplished with the patient in a reclining, flat position (Butler, 2009). • Revise the pouching system: o Increase the size of the opening in the skin barrier/wafer. Cut radial slits or darts in the skin barrier/wafer to accommodate changes in the size of the stoma. o Use a larger/longer pouch to accommodate the size and length of the prolapse (Husain & Cataldo, 2008). • Encourage a back-lying position for sleeping. PROLAPSE Description Assessment Potential complications: • Poor fit of the pouching system (Bafford & Irani, 2013). • Mucosal irritation or ulceration (Husain & Cataldo, 2008). • Obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation (Bafford & Irani, 2013; Husain & Cataldo, 2008). Nursing Intervention Patient/caregiver education • Reassure the patient that the stoma should continue to function without difficulty. • Provide counseling regarding body image, as needed. • Teach the patient: o Skin care and pouching procedures. o To monitor the stoma for changes in color, irritation, laceration or bleeding. o To notify their physician for changes in color of the stoma or increased abdominal pain. o To call their healthcare provider or ostomy nurse, or seek emergency care if signs and symptoms of blockage, obstruction, incarceration or strangulation occur such as: Decreased or no output. Pain, abdominal cramping. Distension around the stoma. Nausea. Refer to the primary healthcare provider • Ischemia, obstruction or inability to reduce the stoma, which warrants a surgical evaluation or intervention (Butler, 2009). WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 12 RETRACTION Assessment Definition Identifying characteristics • A retraction occurs when a stoma is drawn or pulled below • With a retraction, all or part of the stoma is the skin level (Shabbir & Britton, 2010). located below the skin level or the surrounding skin pulls inward due to tension. • A retraction may involve an entire stoma, or it may be limited to the mucocutaneous junction. • Depth of the retraction may increase when the patient is in a sitting or supine position, and the • Retractions are more common in patients with ileostomies or stoma may not be visible when the patient sits with Crohn’s disease, possibly due to the short and stiff upright (Butler, 2009). mesentery that has been thickened by edema. • The presence or severity of a retraction can also be affected by peristalsis (Butler, 2009). Contributing factors/risks Assessment parameters • An abdominal wall opening that is larger than the bowel • Observe for excessive pressure from use of (Butler, 2009); infection; a mucocutaneous separation convexity or a belt (Butler, 2009). (Black, 2009; Butler, 2009); a necrotic stoma (Black, 2009). • Assess for leakage and peristomal skin irritation due to feces or urine undermining the pouching • Premature removal of the supporting device from a loop stoma (Butler, 2009); a stoma located in a skin fold. system: o Fecal—severe skin erosion/ulceration. • Malnourishment, obesity, steroid use, or immunosuppression o Urine—encrustation, ulceration, and stenosis. (Bafford & Irani, 2013; Kann, 2008). • After removing the pouching system, observe the • Tension on the stoma due to: stoma and abdominal contours as the patient o Excessive scar/adhesion formation; excessive weight gain. changes position. o Poor fixation of the bowel to the fascial layer; a short mesentery. o Inadequate length of the stoma (Black, 2009; Butler, 2009). o Recurrent malignancies (Black, 2009). o Radiation damage to the bowel or mesentery (Black, 2009). o A fatty mesentery and well developed panniculus (Shabbir & Britton, 2010). Potential complications (Kann, 2008): • Leakage of the pouching system; peristomal skin irritation; a mucocutaneous separation; stomal stenosis. Description Nursing Intervention Prevention • Encourage patients to manage their weight to avoid stomal retraction and the associated pouching difficulties and complications which can result (Arumugam et al., 2003). Management • Evaluate the pouching system (Butler, 2009). • Consider use of convexity, a belt, skin barrier rings, strips, or paste (Butler, 2009). • Consider use of a custom-made silicone or rigid faceplate. • Consider use of a liquid skin barrier film. Patient/caregiver education • Teach the patient skin care and pouching procedures. • Encourage the patient to attain/maintain ideal body weight. Refer to the primary healthcare provider • A complete mucocutaneous separation that is accompanied with retraction of the stoma below the fascia, which is considered a surgical emergency (Kann, 2008). • Recurrent pouching difficulties, which may require surgical revision to advance the bowel and create a budded stoma (Black, 2009). WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 13 STENOSIS Assessment Nursing Intervention Definition Identifying characteristics Prevention • Stenosis is a narrowing or contracting of the stomal • With stenosis there is a small, narrow opening in the • Maintain a secure pouch seal to prevent skin irritation. opening that may occur at the skin or fascial level. stoma, which impairs drainage from the stoma. • Promptly treat hyperplasia by cauterization with silver nitrate o It is considered an early complication (Butler, (may require a written order), and make modifications in the 2009), but it can also be a late stomal complication pouching system to ensure that fecal or urinary drainage does (Husain & Cataldo, 2008). not come into contact with the peristomal skin (Butler, 2009). • Avoid routine dilation of the stoma (Butler, 2009). • Maintain adequate hydration (Butler, 2009). Contributing factors/risks Assessment parameters Management • Alkaline encrustation in urinary stomas. • Perform a gentle digital examination using a • For fecal stomas, stool softeners, laxatives, and low residue lubricated, gloved finger to assess the size and diets may be needed for stool to pass through the narrowed • Excessive scar tissue formation at the skin or fascial mobility of the skin and fascial rings (Butler, 2009; opening (Butler, 2009). level due to repeated dilation of the stoma or keloid Colwell et al., 2004). • Surgery may be needed for severe complications (Butler, scars. o If it is not possible to perform a digital 2009). • Epithelial hyperplasia (Black, 2009; Butler, 2009). examination, a small, rubber catheter can be used • Inadequate excision of the skin during construction to conduct a retrograde contrast study (Butler, of a stoma. 2009; Colwell et al., 2004). • Inadequate suturing of the fascial layer. o If further testing is indicated, such as a retrograde • Mucocutaneous separation. contrast study, refer to a surgeon. • Peristomal sepsis (Butler, 2009). • Observe for signs of stomal obstruction: • Prior irradiation of the bowel segment. o Fecal diversions. Abdominal cramps; episodes of diarrhea; • Recurrent disease (e.g., cancer, Crohn’s disease, or excessive and loud flatus; explosive passage of tumor growth). stool; narrowed caliber of stool. • Recurrent episodes of skin irritation. o Urinary diversions. • Stomal ischemia, necrosis, or retraction (Butler, Decreased urinary output; flank pain. 2009; Kann, 2008). Evidence of high residuals of urine in the conduit such as urine passing from the stoma in a projectile fashion, or when catheterized, large amounts of urine immediately passing from the stoma. Recurring urinary tract infections. Potential complications Patient/caregiver education • Stricture that acts as a mechanical obstruction • Teach the patient skin care and pouching procedures. (Bafford & Irani, 2013). • Urinary Diversion: Instruct the patient about the signs/symptoms of urinary tract infection. • Fecal Diversion: Teach the patient strategies to prevent constipation. Refer to the primary healthcare provider • Symptoms of partial or complete obstruction, which may require surgical revision. Description WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 14 Research Recommendations A search of the literature revealed that the evidence base for stomal complications and the management consists primarily of expert opinion. Further descriptive or exploratory research studies are needed to address the following areas: • • • • • • • • • Evaluate the technique, complications, reliability and validity of findings of the mini-endoscopy technique (i.e., test tube procedure) for assessing stomal necrosis. Describe the characteristics of patients who develop peristomal hernias. Describe the efficacy of various pouching systems to manage peristomal hernias and mucocutaneous separations. Determine nursing measures that can help prevent peristomal hernias. Determine if routine dilation is effective to manage stomal stenosis, or if the procedure contributes to the development or worsening of stenosis. Describe the effectiveness of vitamin C tablets or cranberry juice to acidify urine or reduce the occurrence of encrustation. Identify if there are any specific long-term activity restrictions that can reduce the incidence of stomal prolapses and peristomal hernias. Describe the efficacy of cold compresses or sugar to facilitate manually reducing stomal prolapses. Identify if the early use of convexity contributes to the development of mucocutaneous separations. WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 15 Glossary Calcium alginate: A non-woven, non-adhesive wound care product derived from seaweed. Fascia: Fibrous connective tissue. Flange: The rigid ring on a two-piece skin barrier/wafer onto which the pouch snaps. Hernia: A protrusion of any viscus from its surrounding tissue walls. Hernias are classified by anatomic location, contents of the hernia, and whether the hernial contents are reducible, strangulated, or incarcerated (Byars, 2011). Hydrofiber: A nonwoven, cotton-like wound care product made of carboxymethylcellulose fiber. Hyperplasia: An overgrowth of tissue. Incarcerated hernia: A hernia that is firm, often painful, and non-reducible by direct manual pressure hernia (Byars, 2011). Melanosis coli: Discoloration of the colon due to chronic use of anthraquinone laxatives containing aloe, senna, and cascara components, which occur naturally in plants. These laxatives are poorly absorbed. When used chronically, they produce a characteristic brown pigmentation of the colon known as “melanosis coli” (McQuaid, 2012). Reducible hernia: The hernial sac is soft and easy to replace back through the hernia neck defect (Byars, 2011). Slough: Moist brown, gray, yellow, or tan necrotic tissue that may appear mucus-like, thin, or stringy. Strangulated hernia: The hernia presents with severe, exquisite pain at the hernia site, often with signs and symptoms of an intestinal obstruction, a toxic appearance, and, possibly, skin changes overlying the hernial sac. A strangulated hernia is an acute surgical emergency. Strangulation develops as a consequence of incarceration and implies impairment of the arterial or blood flow (Byars, 2011). WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 16 References Arumugam, P. J., Bevan, L., Macdonald, L., Watkins, A. J., Morgan, A. R., Beynon, J., & Carr, N. D. (2003). A prospective audit of stomas--analysis of risk factors and complications and their management. Colorectal Disease, 5(1), 49-52. Bafford, A. C., & Irani, J. L. (2013). Management and complications of stomas. The Surgical Clinics of North America, 93(1), 145-166. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2012.09.015 Black, P. (2009). Managing physical postoperative stoma complications. British Journal of Nursing, 18(17), S4-10. Boyd-Carson, W., Thompson, M. J., & Boyd, K. (2004). Mucocutaneous separation. Clinical protocols for stoma care: 4. Nursing Standard, 18(17), 41-43. Butler, D. L. (2009). Early postoperative complications following ostomy surgery: A review. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 36(5), 513-9; quiz 520-1. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e3181b35eaa Byars, D. (2011). Hernias in adults: Introduction, in tintinalli’s emergency medicine: A comprehensive study guide (7th ed.). Retrieved June 18, 2013 from http://accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aid=6361466 Carlsson, E., Gylin, M., Nilsson, L., Svensson, K., Alverslid, I., & Persson, E. (2010). Positive and negative aspects of colostomy irrigation: A patient and WOC nurse perspective. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 37(5), 511-6; quiz 517-8. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e3181edaf84 Colwell, J. C., Goldberg, M. T., & Carmel, J. E. (2004). Stomal and peristomal complications. Fecal & urinary diversions: Management principles (pp. 308-325). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. De Raet, J., Delvaux, G., Haentjens, P., & Van Nieuwenhove, Y. (2008). Waist circumference is an independent risk factor for the development of parastomal hernia after permanent colostomy. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 51(12), 1806-1809. doi:10.1007/s10350-008-9366-5 Franz, M. G., Robson, M. C., Steed, D. L., Barbul, A., Brem, H., Cooper, D. M.,...Wound Healing Society. (2008). Guidelines to aid healing of acute wounds by decreasing impediments of healing. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 16(6), 723-748. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00427.x Fulham, J. (2008). Providing dietary advice for the individual with a stoma. British Journal of Nursing, 17(2), S22-7. Grant, M., McMullen, C. K., Altschuler, A., Hornbrook, M. C., Herrinton, L. J., Wendel, C. S.,...Krouse, R. S. (2012). Irrigation practices in long-term survivors of colorectal cancer with colostomies. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16(5), 514-519. doi:10.1188/12.CJON.514-519 Hatton, S., & Brierley, R. (2011). Irrigation as an option for stoma management. Gastrointestinal Nursing, 9(7), 6-7. Heo, S. C., Oh, H. K., Song, Y. S., Seo, M. S., Choe, E. K., Ryoo, S., & Park, K. J. (2011). Surgical treatment of a parastomal hernia. Journal of the Korean Society of Coloproctology, 27(4), 174-179. doi:10.3393/jksc.2011.27.4.174 Husain, S. G., & Cataldo, T. E. (2008). Late stomal complications. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 21(1), 31-40. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1055319 WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 17 Kann, B. R. (2008). Early stomal complications. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 21(1), 23-30. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1055318 Maeda, K., Maruta, M., Utsumi, T., Sato, H., Masumori, K., & Aoyama, H. (2003). Pathophysiology and prevention of loop stomal prolapse in the transverse colon. Techniques in Coloproctology, 7(2), 108-111. doi:10.1007/s10151-003-0020-x McQuaid, K. R. (2012). Drugs used in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases, in basic & clinical pharmacology, 12th ed. Retrieved June 18, 2013 from http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=55832807 Perston, Y. (2010). Ensuring effective technique in colostomy irrigation to improve quality of life. Gastrointestinal Nursing, 8(4), 18-22. Randall, J., Lord, B., Fulham, J., & Soin, B. (2012). Parastomal hernias as the predominant stoma complication after laparascopic colorectal surgery. Surgical Laparoscopy, Endoscopy & Percutaneous Techniques, 22(5), 420-423. Ratliff, C. R., Scarano, K. A., Donovan, A. M., & Colwell, J. C. (2005). Descriptive study of peristomal complications. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 32(1), 33-37. Rolstad, B. S., & Beaves, C. (2006). 2006 update: Principles and techniques in the use of convexity. Retrieved 2013 from http://www.hollister.com/us/files/case_studies/907634.pdf Shabbir, J., & Britton, D. C. (2010). Stoma complications: A literature overview. Colorectal Disease, 12(10), 958-964. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02006x Thompson, M. J. (2008). Parastomal hernia: Incidence, prevention and treatment strategies. British Journal of Nursing, 17(2), S16-S20. Varma, S. (2009). Issues in irrigation for people with a permanent colostomy: A review. British Journal of Nursing, 18(4), S15-8. Williams, J. (2011). Principles and practices of colostomy irrigation. Gastrointestinal Nursing, 9(9), 15-16. Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. (2005). Stoma complications: Best practice document for clinicians. Retrieved 2013 from http://www.wocn.org/?page=StomaCompsClinician Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. (2007a). The WOCN image library. Retrieved 2013, from http://www.wocn.org/page/ImageLibrary Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. (2007b). Convex pouching systems: A best practice document for clinicians. Mount Laurel, NJ: Author. Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. (2010). Management of the patient with a fecal ostomy: Best practice for clinicians. Mount Laurel, NJ: Author. Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. (2011). Peristomal hernia: Best practice for clinicians. Mount Laurel, NJ: Author. WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 18 Appendix Images of Stomal Complications Figure 1. Peristomal Hernia; Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 2007 WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 19 Figure 2. Stomal lacerations; Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 2007 WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 20 Figure 3. Mucocutaneous separation, Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 2013 WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 21 Figure 4. Necrosis, Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 1997 WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 22 Figure 5. Prolapsed stoma; Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 2007 WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 23 Figure 6. Retracted stoma; Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 2007 WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 24 Figure 7. Stenosis; Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 2007 Acknowledgment about Content Validation This document was reviewed in the consensus-building process of the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society known as Content Validation, which is managed by the Center for Clinical Investigation. WOCN® National Office ◊ Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 www.wocn.org 25