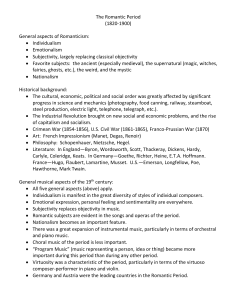

The Romantic Period Workbook

advertisement

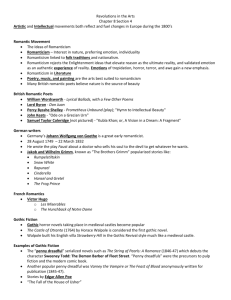

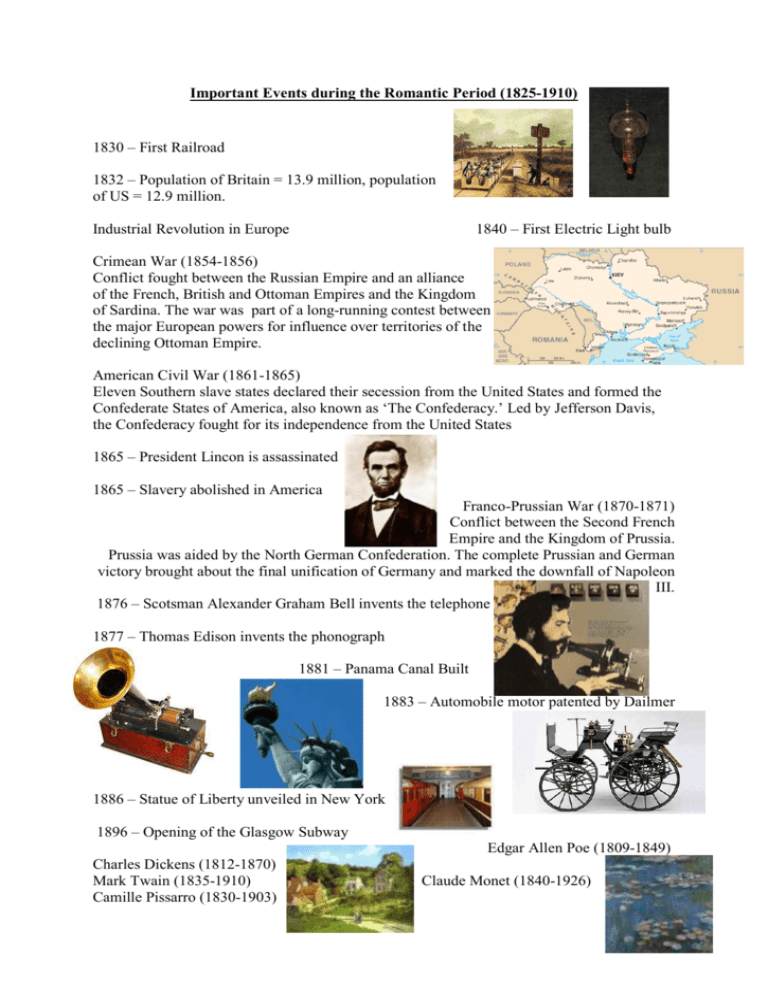

Important Events during the Romantic Period (1825-1910) 1830 – First Railroad 1832 – Population of Britain = 13.9 million, population of US = 12.9 million. 1840 – First Electric Light bulb Industrial Revolution in Europe Crimean War (1854-1856) Conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French, British and Ottoman Empires and the Kingdom of Sardina. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining Ottoman Empire. American Civil War (1861-1865) Eleven Southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America, also known as ‘The Confederacy.’ Led by Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy fought for its independence from the United States 1865 – President Lincon is assassinated 1865 – Slavery abolished in America Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) Conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation. The complete Prussian and German victory brought about the final unification of Germany and marked the downfall of Napoleon III. 1876 – Scotsman Alexander Graham Bell invents the telephone 1877 – Thomas Edison invents the phonograph 1881 – Panama Canal Built 1883 – Automobile motor patented by Dailmer 1886 – Statue of Liberty unveiled in New York 1896 – Opening of the Glasgow Subway Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849) Charles Dickens (1812-1870) Mark Twain (1835-1910) Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) Claude Monet (1840-1926) Romantic Vocal Music Leid Leid Word Painting GERMAN Strophic PIANO Through Composed Leid: This term (the German word for song) refers specifically in the Romantic era to works for solo voice and piano. The text is in German, the structure of the verses is strophic and through composed. An important feature is that the voice and piano are equally important. A direction to the performer which allows freedom to change speed, thus allowing more expression. Song Cycle Song Cycle Word Painting Strophic Through Composed Song Cycle: A group of songs linked by a common theme or with a text written by the same author, usually accompanied by piano but sometimes by small ensembles or full orchestra. Romantic Instrumental Music Overture Overture: A piece of orchestral music which introduces a large-scale work such as an opera, an oratorio, or a musical. Symphony Symphony: A large work for orchestra usually in four movements. Symphonic/Tone Poem Symphonic Poem Tone Poem Programme Music Leitmotif Symphonic/Tone Poem: A one-movement piece for orchestra which tells a story or maybe relates an experience from the composer’s life. Tone poems were found in the Romantic era and were also known as symphonic poems. Concerto Concerto: Work for solo instrument and orchestra, e.g. a flute concerto is written for flute and orchestra. It is normally in three movements – Fast, Slow, Fast. Cadenza: A passage of music which allows soloists to display their technical ability in singing or playing an instrument. Performers used to improvise cadenzas themselves but eventually composers began to write them into the score. In a concerto the end of the cadenza is usually marked by a dominant 7th chord. Nicola Benedetti performing Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto. There are four great Romantic violin concertos that have become the first call of the violinist the world over: the Brahms, the Tchaikovsky, the Mendelssohn and the Beethoven. Leitmotif Leitmotif: A theme occurring throughout a work which represents a person, an event or an idea, etc. The first composer to use leitmotiv extensively was Wagner, in his operas. Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (made popular by the Disney film Fantasia) contains one of the most famous leitmotifs in Classical music. More recently, Jaws features an iconic leitmotif. Early Romantic Period One of the key features of Romantic music is its strong association with other art-forms, particularly literature or painting. Schubert responded instinctively to the poetry and drama of the great literary figures of his time, setting the way for this new period of musical history. Another key feature was a response to nature, most famously reflected in Beethoven’s 6th symphony. Artists began to portray emotion like never before and created fantastical images in programme music. Liszt’s newly invented ‘tone poem’ proved an ideal vehicle for musical responses to literature or art. Another hallmark of Romanticism was its emphasis on the individual – the composer or the performer. The 19th century saw the rise of the star performer and with it a division between creator and executant which became progressively more marked in the 20th century. Many 19th century composers (Chopin, Liszt, Brahms, Paganini) carried on the tradition followed by Mozart and Beethoven in writing music for themselves to perform but they also began to write for other virtuoso executants such as the pianist Clara Schumann and clarinettist Richard Muhlfeld. However, the Romantic manifesto was perhaps best advanced by the further rise of the pianist-composer (equivalent to the term singer-songwriter nowadays) which included Chopin, Schumann, Mendelssohn and Liszt. Gioacchino Rossini (1784-1886) – Italian Rossini specialised in opera, turning out a steady flow of the works between 1810 and 1822, both comic and serious, for production in Venice, Milan, Naples, and Rome. These include The Barber of Seville and The Thieving Magpie. One of his innovations included the replacement of keyboardaccompanied recitative with orchestral accompaniment, the expansion of the chorus, the development of the coloratura aria and the revitalization of opera buffa; his characters such as Figaro are real people who audiences of all ages can identify with. At the age of 31 he moved to Paris where he wrote several more operas including his masterpiece William Tell. Arguably his most famous work, with its overture a staple of concert programmes today, he stopped composing after William Tell for 34 years. Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) - French Like Schumann and Chopin, Berlioz is regarded as an archetypal ‘Romantic’ artist, both for the nature of his work and for the colourful events of his life. Unlike others, Berlioz worked with huge, colourful brushstrokes which reflected his sensitive, passionate and impulsive nature. One of his greatest and most performed works, Symphonie Fantastique, was written in response to his obsession with the Irish actress Harriet Smithson who he saw as Ophelia in Hamlet. He then went after her with all the obsession of a stalker, following her morning noon and night. When his advances failed, he wooed someone else (Camille) in an attempt to make Harriet jealous. By this time he had also won the Prix de Rome, a major compositional prize in Paris which won him a place to study in Rome. When in Rome however, he heard that Camille had taken a lover which ruined his plan of making Harriet jealous. So he immediately headed back to Paris disguised as a lady’s maid, getting as far as Genoa before losing his disguise. When he returned to Paris he found out that Harriet was in town and decided to woo her with an arrangement of his Symphonie Fantastique (5 movements which contains 4 brass bands and a Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath). It worked and they married in 1832! Symphonie Fantastique is an amazing piece of programme music, subtitled ‘Episodes in the life of an artist.’ In the first three of its five movements, ‘the beloved’ appears in various transformations as a melodic motif (which Berlioz called the idee fixe), whether in ‘passions and dreams,’ at a ball or during a pastoral idyll (which owes much to Beethoven). In the fourth movement, the artist dreams that he has murdered his beloved and is being led to the guillotine; in the last, a grotesque witches’ Sabbath, the beloved has been transformed into a hag, her theme obscenely distorted. The symphony contains a ‘Harriet Smithson’ tune (the motif) which crops up throughout the piece. Maybe she was touched? Berlioz’s predilection for the monumental led him to compose enormous scores for huge orchestral forces. His colossal works for chorus and orchestra includes a Requiem, the dramatic symphony Romeo and Juliet and the opera The Trojans. His oratorio The Childhood of Christ is still regularly performed. Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) – German Born into a wealthy musical family, Mendelssohn travelled a great deal as a young man, visiting Switzerland, Italy and Britain. He responded passionately to literature and the people and landscapes he encountered on his travels. In 1825 he wrote the overture to Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The wedding march from this work is still guiding happy couples out of churches today! By 1831 he’d made the first of a long line of trips to Scotland, leading to his Scottish Symphony (programme music in itself) and his famous overture The Hebrides or Fingal’s Cave, prompted by an actual excursion to the cave itself in 1829, where you can hear the waves lapping in the cave in the opening bars.Mendelssohn was obsessed by the work of J.S.Bach which had been more or less forgotten since his death in 1750. A celebrated composer of his time, Mendelssohn resurrected Bach’s Passions and B minor Mass, leading to a revival in the composer’s work as well as that of Handel. He also promoted the careers of other composers including Schumann and Berlioz. Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) – Polish Chopin epitomizes the figure of the Romantic artist – withdrawn, temperamental, talented and doomed to a premature death from tuberculosis. Like Paganini (a virtuoso violinist), he was both a composer and performer with his music establishing the piano as the 19th century’s most popular instrument. Chopin was very much the ‘sensitive’ romantic one, one for whom the word romantic meant pure and subtly intense, reserved even. Born to French and Polish parents he studied at the Warsaw Conservatory before leaving his native Poland complete with an urn of genuine Polish earth which he kept with him to remind himself of home (indeed, he would end up having his urn buried alongside him when he died). Chopin was introduced to the Parisian salon society where his music was a great triumph leading to celebrity status. He was a sought-after teacher, consorted with the wealthy and powerful, and enjoyed the friendship of fellow composers (Liszt, Berlioz, Bellini and Meyerbeer). Apart from the concertos and a handful of pieces for the cello and flute, Chopin’s output is all for solo piano. He borrowed the Irish composer John Field’s new form, the nocturne, and raised it to fresh new heights of subtle expression. His etudes, preludes, waltzes, impromptus and mazurkas were written to exploit and develop piano technique; while the later polonaises, fantaisies, scherzos, ballades, Barcarolle and two sonatas were all virtuoso works. Nationalist Nationalist: Music which in some way reflects the nationality of a country or a composer. Traditional folk melodies, dance rhythms and instruments might be used. The nationalist movement took root in central Europe, where in the 1830s a wave of nationalist sentiment swept through Germany, Poland, Belgium and northern Italy (at that time ruled by Austria). Over the next decade, the desire of autonomous states for political independence from the mighty empires that ruled them coincided with the democratic urge to replace monarchies with republican governments more in tune with the needs of ordinary citizens. This unstoppable force flared into violence in 1848 when patriotic sentiment and revolutionary fervour spread across France, Italy, Germany and central Europe. In music, this patriotic fervour encouraged composers to seek inspiration in their national roots, particularly folk culture. The nationalist movement was particularly strong in Russia where Italian music and Italian composers had long reigned supreme at the cosmopolitan court in St Petersburg. Glinka was the first composer to draw inspiration from the distinctive melodic patterns and rhythms of Russian folk songs and dance, leading to ‘The Mighty Five’ (the nickname given by the critic Vladimir Stasov in 1867) – a curious crowd of drinking buddies and talented composer. ‘The Mighty Five’ consisted of Mily Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, Modest Mussorgsky and Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov. They in turn influence Tchaikovsky who drew inspiration for his music from folk legends and epic tales from Russian history. The central European countries of Bohemia, Slovakia and Hungary, whose native culture had been supressed by centuries of foreign domination, were particularly receptive to the new spirit of nationalism. The Bohemian composer Smetana was the first to celebrate the rich history and characteristic landscape of his native land in a series of tone-poems entitled Ma Vlast (My Homeland) and in a series of operas. He in turn influenced his pupil Dvorak who effortlessly incorporated Czech song and dance idioms into European symphonic structures. Nationalism was by no means confined to central Europe. Edvard Grieg, Norway’s greatest composer, was trained in the German musical tradition but his music draws plentifully on the folk idioms which he picked up on walking excursions into the Norwegian mountains. In Austria, the talented Strauss family turned Vienna into the waltz capital of the world and in England, the quintessentially ‘English’ Savoy Operas of W.S.Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan exploited a rich vein of satirical English humour. Notable Composers of the Nationalist Movement Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) – Russian Arguably the most original of ‘The Mighty Five,’ Mussorgsky was bedevilled by mental instability and exacerbated by heavy drinking. He is remembered most for his orchestral work Night on a Bald Mountain (which features in Disney’s Fantasia) and Pictures at an Exhibition for piano (later orchestrated by Ravel) in addition to his song-cycles. Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884) – Czech Smetana was the first Czech composer to draw inspiration from national legends, history and landscape and incorporate melodic patterns and rhythms of folk music into his work. He is best remembered for his great cycle of symphonic poems celebrating Czech history and legend entitled Ma vlast (My Homeland). The most popular item has always been Vltava which portrays a river running through Prague. Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) – Czech Dvorak succeeded in fusing folk idioms with the symphonic techniques of his predecessors Beethoven and Brahms. His nine symphonies (though particularly the last three – Symphony No.9 From the New World including the theme made famous by the Hovis adverts), tone-poems, chamber and piano music are all part of the mainstream repertoire. Just one year older than Tchaikovsky, he learned to play the violin and viola and as a young man played in the Czech National Theatre where his musical director was Smetana. At the age of 33 he won an Austrian composing competition. Johannes Brahms was on the jury panel and was very impressed by Dvorak’s work. He introduced Dvorak to his publisher – an important step in becoming musically solvent. From here on in he was made Professor of Music at the Prague Conservatoire and later the director of the new music school in New York. Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian Grieg was Dvorak’s Scandinavian equivalent – a composer working outside the mainstream European symphonic tradition though trained within it, bringing a warmth and natural melodic facility that owed much to the folk music of his native land. Much of Grieg’s music is instantly recognisable due to its use in films and the media. His famous works include the Peer Gynt suites which includes Morning and In the Hall of the Mountain King. However, it is perhaps his only piano concerto with its famous opening for which he is best remembered for. The Nationalist movement also gave way to ‘The Waltz Kings’ – Johann Strauss the elder and Johann Strauss the younger, the latter being his father’s eldest son and now referred to as ‘The Waltz King.’ The Vienna Philharmonic have a long tradition of playing their vast repertoire and that of their contemporaries on New Year’s Day which is broadcast to over 50 countries including the United Kingdom. Late Romantic Music of the late 19th century and early 20th century which retains the dramatic intensity of earlier 19th century music. The music is characterised by the use of vast instrumental forces, increased chromaticism and large-scale compositions. Composers included Wagner, Mahler and Richard Strauss. As the 19th century moved into its second half, many social, political and economic changes set in motion in the post-Napoleonic period became entrenched. Railways and the electric telegraph bound the European world ever closer together. The nationalism that had been an important strain of early 19th century Romantic music became formalised by political and linguistic means. The dramatic increase in musical education brought a still wider sophisticated audience, and many composers took advantage of the greater regularity of concert life, and the greater financial and technical resources available. These changes brought an expansion in the sheer number of symphonies, concertos and tone poems which were composed, and the number of performances in the opera seasons in Paris, London and Italy. Two musical giants dominated the second half of the 19 th century – Johannes Brahms and Richard Wagner. Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) – German Brahms saw himself as belonging to the mainstream German symphonic tradition. He must a massive admirer of Beethoven and his principle of motivic construction. Brahms’ four symphonies represent ‘pure,’ abstract music: unusually for a Romantic composer, they are unaffected by external influences such as literature or landscape. vs Richard Wagner (1813-1883) - German Wagner’s works are almost entirely operatic. One of the most forceful and influential characters in music history, Wagner was highly receptive to influences of all descriptions – literature, myth, drama, poetry, painting, politics and philosophy. He strove to unite drama, music, poetry and the visual arts in his gigantic later operas. The operas and tone poems of Richard Strauss owe an enormous debt to Wagner, as do the symphonies of Bruckner and Mahler (though both were equally influenced by Brahms). Wagner’s influence was so inescapable and his genius so persuasive that the more unpleasant aspects of his personality – particularly the virulent anti-Semitism expressed in his polemical writings, which certainly contributed to the climate of opinion in Germany that led to Hitler’s National Socialism – tend to be overlooked. Wagner was the first composer to use leitmotiv extensively in his operas. The conductor Sir Thomas Beecham is reported to have said ‘We’ve been rehearsing [this opera] for two hours now and we’re still playing the same bloody tune!’ Wagner’s famous Ring Cycle lasts 15 hours in total. Late Romantic = MASSIVE TUNES with LOTS OF ORCHESTRAL COLOURS AND EFFECTS. Late Romantic Opera As in the early part of the century, Italian music continued to be dominated by opera but in a very un-Wagnerian style. Giuseppe Verdi took over from Rossini producing a sequence of 26 operas (including his famous Aida) over 57 years which have since remained the backbone of the international repertoire. Verdi was Wagner’s only real rival in the operatic field but his works are firmly based in the bel canto tradition. His successor Giacomo Puccini wrote far fewer works but almost all have help their place in the operatic canon. Puccini owed his success to an unerring sense of theatre and a persuasive melodic gift, allied to a taste for sentimental plots which still reduce audiences to tears such as Madame Butterfly and Tosca. The Late Romantic/Nationalist Crossover Artist By the second half of the 19th century nationalism was in full swing and few composers remained untouched by an awareness of their national culture. Mahler in Austria, Sibelius in Finland, Faure in France, Elgar in England and Rachmaninov in Russia all made original contributions to the musical literature of their respective countries, broadly working with the language of late Romanticism. Mahler and Sibelius were skilled symphonic writers. Rachmaninov inherited Tchaikovsky’s ability to write superb tune, expressed with a passion that seems essentially ‘Russian.’ Elgar occupies a special place in British music as the most gifted English composer since Purcell. He wrote the most beautiful music ever conceived, including his elegiac Cello Concerto. His face now appears on English twenty pound notes: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) – Russian Perhaps the world’s most popular ‘classical’ composer, Tchaikovsky’s music has always held a special appeal for its passion, lyricism, extravagant emotionalism and glowing orchestra colour. It reflects the temperament of its composer – a moody, melancholy character, prone to fits of depression but also of a heightened sense of optimism. This is often reported to reflect his struggle with his homosexuality (some scholars believe he was poisoned over this later in life with contaminated water) and his struggle in losing his mother (who he was very close to) at the age of 14 to cholera. His music draws on a rich vein of Russian folk culture which he successfully fused with the Western symphonic tradition. He wrote: ‘As far as the Russian element in my music is concerned, this is because I grew up in the provinces, imbued from earliest childhood with the indescribable beauty of the characteristic features of Russian folk music.’ BIG Tchaikovsky loved , lush tunes which his audience would leave the concert hall humming. Brahms also loved big tunes but he was much more conservative in his writing, harking back to the examples of Beethoven. Brahms reportedly hated Wagner and Tchaikovsky apparently hated Brahms! One of his earliest works, the tone-poem Romeo and Juliet has become one of his most celebrated works, allowing the composer to deal with his favourite themes of love and death. Between 1877-1892 he wrote some of his most famous and beloved ballet scores – Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. During this time he began his long association with Nadezhda von Meck, the widow of a railway tycoon, who befriended the composer, commissioned his works and supported him financially on the condition that they should never meet. In fact, the Impressionist composer Debussy, was a sort of live-in musician for von Meck for many years. As you will see in the next chapter, the music of Debussy is very different to that of Tchaikovsky. Von Meck’s patronage enabled Tchaikovsky to concentrate on composition and rescued him from the emotional chaos caused by his hasty marriage to a mentally unstable music student who had pestered him with love letters. In 1896, three years after his death, she was declared insane and spent the rest of her life in an asylum. In his later life, his work is increasingly dominated by the idea of Fate, as shown in his operas Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades and perhaps his most played symphony – Symphony no.5.In 1880 he commemorated the historic defeat of Napoleon’s army with the brash but ever-popular 1812 Overture. Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) – Russian Rachmaninov was the last of a great tradition of great pianistcomposers of the Russian Romantics. The dramatic sweep of his music, combined with a haunting Russian melancholy, holds a powerful appeal. His three symphonies and four piano concertos are much loved. Rachmaninov had unusually large hands which was an advantage for the virtuoso pianist. Much of his music is notoriously difficult – the Oscar-winning film Shine depicts Geoffrey Rush’s mental torment in mastering his Third Piano Concerto. The dangerous political instability of Russia forced his family into exile in 1917, first to Sweeden, the America where he composed one of his most celebrated works – Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. NEW INVENTIONS!!! The saxophone was invented in 1846 by Adolphe Sax. Since its introduction into French infantry music, the saxophone has steadily gained favour in military bands. Romantic composers experimented with the saxophone within the symphony orchestra – Richard Strauss used a saxophone quartet in his Symphonia domestica of 1902. George Bizet (composer of the opera ‘Carmen’) includes a famous alto solo, while Ravel (Boero), Prokofiev (Romeo and Julliet) and Vaughan Williams (Symphony no.6) have also used the saxophone. Since WWI the saxophone has become extremely popular in music of all kinds. Since the 1930s it has played a leading role in jazz bands and it is in this medium that the instrument’s potential has been most thoroughly exploited. Between the 1930s-60s, saxophone consorts of the four main types featured strongly in big bands such as those led by Glen Miller and Duke Ellington in the United States, Henry Hall in England Bert Kaempfert and James Last in Germany.