The Inspiring Role of Worker Poetry in a BC Labour Newspaper

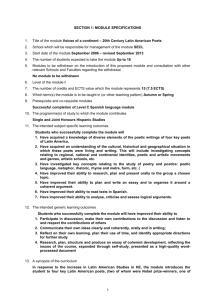

advertisement