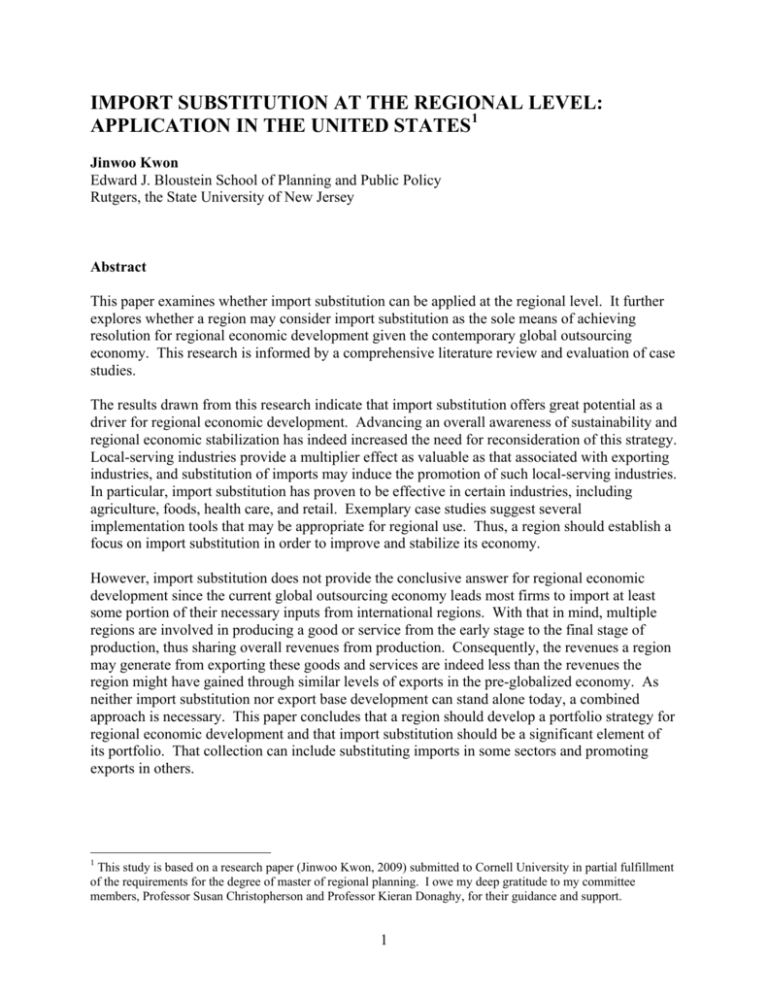

import substitution at the regional level

advertisement