Appeasement, Consciousness, and a New Humanism: Ellison's

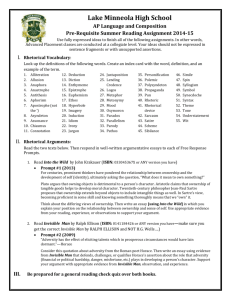

advertisement

I first became captivated with the ideas of Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Ralph Waldo Ellison my senior year of high school. I was exposed to Up from Slavery and The Souls of Black Folk while taking a small honors consortium seminar on the Progressive Era, and I first read Invisible Man in my AP English Literature class. At the time, I could not stop thinking of the connections among the three texts, though because I was reading them in separate classes I could not explore these connections to the depth I desired. Thus, when I got to Duke and saw there was a whole academic writing class devoted to Ellison’s Invisible Man I jumped at the chance to register. While taking the class, I had the great opportunity to investigate the nuances of Ellison’s momentous text under the guidance of my outstanding professor Dr. Lena Hill, whose insight and direction precipitated and amplified my initial philosophical interest in the novel. As a result, when we were given pretty free reign on topics for our final term papers, I quickly decided to write mine on Ellison’s engagement with the ideas of Washington and Du Bois in Invisible Man, finally producing this paper. 24 Appeasement, Consciousness, and a New Humanism: Ellison’s Criticism of Washington and Du Bois and His Hope for Black Americans Nick Cuneo R alph Waldo Ellison’s novel Invisible Man (1947) is a first-person account of the feelings, prejudices, and contradictions concomitant to being black in America. This work of fiction is illuminated by comparison to two landmark nonfiction works in African American history written nearly 50 years earlier, Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery (1901) and W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903). Despite ostensible similarities among the books, each portrays a very different outlook on the future of black Americans. While Washington advocated for blacks to embrace a Protestant work ethic, a tolerance of segregation, and a submissive attitude in hopes of impressing whites into granting them proper recognition, Du Bois explored the concept of double-consciousness — the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others,” which he claimed black Americans needed to reconcile — and called for blacks to militantly demand their political and civil rights (Du Bois 25). Though Ellison’s narrator, Invisible Man, exhibits aspects of each ideology throughout his development, he ultimately veers away from both as he submerges into his hole beneath Harlem, alone and invisible. In this essay, I will analyze the protagonist’s journey from Founder-worshipping naïf to defeated and cerebral author and show how it reflects a direct criticism of both Washingtonian appeasement and, more subtly, the dangers of the militancy, estrangement, and destruction which can result from failing to resolve the conflict of Du Bois’s two irreconcilable selves. I will conclude that Ellison not only criticizes but in fact rejects both ideologies and offers instead, through the visceral and deeply human voice of the Narrator, his own philosophical position: that blacks might embrace their individuality and common humanity rather than fixate on issues of race and nationality. Invisible Man starts his journey as a successful and optimistic high school graduate whose Washingtonian speech arguing that “humility was ... the very essence of progress” earns him the opportunity to speak at a public ceremony in town (Invisible Man 5, hereafter IM). The Narrator implicitly criticizes his young self’s alignment with Washington at the very start of the novel, however, when, after establishing a link between his invisibility and maturity, he overtly states, “in those pre-invisible days I visualized myself as a potential Booker T. Washington” (18). Yet it is the subsequent acts of indignity and oppression to which the protagonist is exposed that shed the greatest light on the failure of Washington’s policy of passive obedience. The first such humiliation occurs when he is brought to the ballroom of a fancy hotel under the pretense of giving his graduation speech to the town’s most powerful white men, only to discover there would be a battle royal-style boxing match in which he would be forced to participate. Throughout the physical and psychological abuse of the battle royal, the Narrator keeps telling himself that if he impresses the white men he will be rewarded. However, by allowing himself to be blindfolded and manipulated by the whites, he is only allowing them to further degrade him to a point at which even he admits, “I had no dignity” (22). Though it is clear that the more the young black men acquiesced to the expectations of the whites, the “more threatening the [white] men became,” Invisible Man still concerns himself with pleasing the whites in search of an elusive reward, repeatedly asking himself, “Would they recognize my ability? What would they give me?” (24). At first the protagonist’s Washingtonian strategy seemingly pays off, as he ends up with both “gold coins” and a scholarship to the black state college. However, the value of these rewards is soon called into question by the protagonist’s realization that the gold pieces are really worthless brass tokens and through his subsequent dream in which he opens the same envelope that contained his scholarship and instead finds the sinister message, “Keep This NiggerBoy Running” (33). Ellison further links the physical act of running to Washingtonian appeasement through his direct criticism of Washington, his white supporters, and his Tuskegee Institute. Ellison’s modeling of the Narrator’s school after Tuskegee is evident from the state in which it is located (Alabama) to its “founder” and his life story to its mission to provide vocational training to blacks. However, Ellison’s criticism of the physical school is more metaphorical, as the Narrator describes the campus as “white-washed,” with buildings “bleached white” and the main statue covered in “white chalk” (46). From the excessively white edi- fices to the negro spirituals performed for the sole enjoyment of the visiting white donors, it is clear that this is not a school at which blacks are educated for their own sake but rather are looked after by whites with ulterior motives. This paternalism is symbolized by the ubiquitous moon —“a white man’s bloodshot eye” —which illuminates the college and its students like a police officer’s probing flashlight (110). By metaphorically and symbolically linking the Institute to white paternalism, Ellison implicitly echoes Du Bois’ and others’ criticism of Tuskegee and its vocational curriculum as being more advantageous to the whites who would benefit from the labor of the technically trained blacks it graduated than to the blacks themselves, who would be kept running for the whites’ benefit. Ellison more directly criticizes Washington through Invisible Man’s interaction with Mr. Norton, a white trustee who helped found the Institute. Invisible Man’s mindset during his time with the Boston liberal stridently echoes Washington’s “Atlanta Exposition,” in which he promised whites that “you and your families will be surrounded by the most patient, faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful people ... [who] shall stand by you with a devotion that no foreigner can approach, ready to lay down [their] lives, if need be, in defense of yours” (Washington 107). While chauffeuring Norton, Invisible Man displays a level of obsequiousness, loy- By metaphorically and symbolically linking the Institute to white paternalism, Ellison implicitly echoes Du Bois’ and others’ criticism of Tuskegee and its vocational curriculum as being more advantageous to the whites who would benefit from the labor of the technically trained blacks it graduated than to the blacks themselves, who would be kept running for the whites’ benefit. 25 26 alty, and opportunism clearly meant to evoke ness. In other words, Invisible Man must face the Washington’s notion of ideal behavior: “I knew... sense of always being observed and judged based on that it was advantageous to flatter rich white folks. the conflict between his two identities, that of being Perhaps he’d give me a large tip, or a suit, or a schol- black and of being an American: The Negro is ... born with a veil, and gifted with a arship next year” (IM 38). Instead of deferring to his second sight in this American world, — a world better judgment in various instances, Invisible Man which yields him no true self-consciousness, but obediently acquiesces to Mr. Norton’s demands in only lets him see himself through the revelation order to show his devotion, patience, and even willof the other world. It is a particular sensation, ingness to risk his own life, in hopes of a pecuniary this double-consciousness ... One ever feels his reward. This strategy, however, fails miserably, as two-ness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, things escalate out of control. Norton ends up abantwo thoughts, two unreconciled strivings, two doning him and Invisible Man gets expelled from the warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged school and sent “running” to Harlem. By having strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. Invisible Man follow all the tenets Washington laid (Du Bois 3) out for blacks and then showing the complete catastrophe that can directly result from it, Ellison goes If the move to Harlem is Invisible Man’s attempt to beyond illustrating that Washington’s prescription become free, it also ushers him into a perhaps more complex set of race relations, eswould not always be effective to By exposing pecially within himself. For there, demonstrate that the effort to follow Invisible Man’s sense of fragmentathose instructions is itself psychologithe protagonist’s tion, his seeing himself from different cally injurious. delusional optimism points of view at the same time, leads Even after both the battle royal as unfounded and to his inability to be whole. and the incident with Mr. Norton, Present throughout black literaInvisible Man maintains his selfactually dysfunctional, ture from Zora Neale Hurston’s defeating Washingtonian mindset Ellison warns Their Eyes Were Watching God when he gets to New York, where he (1937) to Richard Wright’s Black believes if he tries hard enough and ambitious black Boy (1945), the Du Boisian conflict impresses important people he will Americans of the of selves acts as a veil which prevents be allowed back in the Institute. He even has visions of becoming a suc- corrosive, if seductive, a character from being truly self-confident, manifesting itself in an acute cessor to Dr. Bledsoe, the megalomaeffort to placate awareness of one’s status or outward niacal black leader of the Institute appearance. Thus it comes as no surwhose obsession with power leads those who would prise that Invisible Man displays an him to claim he is in control of the undermine them. increased cognizance of his appearwhite trustees. By exposing the protagonist’s delusional optimism as unfounded and ance and any indication of his black southern roots actually dysfunctional, Ellison warns ambitious black once he gets to New York. This heightened selfAmericans of the corrosive, if seductive, effort to awareness is evident from the very beginning, when, placate those who would undermine them. Final- armed with Bledsoe’s letters to prominent trustees, ly, Ellison goes so far as to implicitly compare Invisible Man arrives at the Men’s House eager to Washingtonian appeasement to slavery or imprison- find “someone to show the letters to, someone who ment through the words of Mr. Emerson Jr., the dis- could give me a proper reflection of my imporillusioned son of the powerful white business-owner tance.” When he goes to the mirror and gives himto whom Invisible Man, armed with a confidential self an “admiring smile” as he spreads the letters out letter from Dr. Bledsoe, appeals for a job. Emerson on the dresser, Invisible Man is almost literally Jr. shows Invisible Man how ironic and futile his seeing himself through a white man’s — a real Washingtonian pursuit of success has been by American’s? — eyes (IM 163). revealing Bledsoe’s malicious nature, after which he As Invisible Man gets further enveloped in othdeclares, “You have been freed” (192). ers’ perceptions of him, he becomes hyperconscious At this point in the novel, Invisible Man has yet of his superficial appearance, as seen both in the to overcome his sense of Washingtonian obedience, final text and (particularly well) in earlier drafts of though he may understand it is not a foolproof pre- Invisible Man. Upon coming to New York, Invisible scription for success for an intelligent black man. Man admits, “I followed the fashion magazines reliWhen he gets to Harlem, however, he also has to giously, stood for hours watching men come and go confront a dilemma W.E.B. Du Bois famously and through the portals of Brooks Brothers and finally extensively explored in The Souls of Black Folk, almost broke myself buying the correct suits ...” namely the phenomenon of black double-conscious- (“Ralph Ellison Papers,” Box 142). This desire to conform is also apparent in the protagonist’s reactions when people mention his southern background. He feels indignant, for instance, when his waiter offers him the country special of pork chops and grits on the way to his last interview (IM 178). Furthermore, Ellison irrefutably echoes Invisible Man’s Du Boisian double-consciousness in the drafts while he is attempting to contact the powerful trustees: “I discovered myself staring at the paneled wall behind which the young woman had disappeared sweeping its rich and beautifully joined woods for peepholes. For I had the sense of being observed” (my emphasis, “Ralph Ellison Papers,” Box 145). Here we see the intersection of Du Bois and Washington, for when following Washington’s edict from the Atlanta Exposition to “cast down your bucket where you are” and cater to whites, ambitious black Americans cannot help but feel a conflict between the obsequiousness Washington demanded toward whites and their own black identity (Washington 106). This connection is also explicitly made by Ellison early in the novel during his description of the black college when he references the notoriously ambiguous statue — modeled after a statue of Washington at Tuskegee — of the Founder lifting a “veil” off of a newly freed slave. However, at that point in the Narrator’s journey, neither he nor the reader knows what to make of it, as the Narrator remembers being “puzzled” about “whether the veil [was] really being lifted, or lowered more firmly in place” while he was at the Institute (IM 36). It is only after Invisible Man’s experiences in New York that it becomes clear that with Washingtonian appeasement comes the lowering of the Du Boisian veil of double-consciousness, not emancipation from it. In fact, it is not until Invisible Man is “reborn” after being electronically lobotomized and given a new identity in the factory hospital of Liberty Paints that he finally breaks away from the confining obedience of Washington and starts exhibiting the militancy Du Bois called for in blacks. And, consequently, it is not until after his hospitalization that the protagonist actually confronts Du Bois’s perpetual conflict and attempts to reconcile his black self with his American one. A catalyst to this reconciliation is to be found in the character of Mary, a strong southern black woman who is motherly and proud of her heritage. That she embraces black culture is a welcome relief to Invisible Man, who has denied his heritage for his whole life. At Mary’s place, Invisible Man finally reconnects with his black identity as exhibited by such acts as his code-switching from common English to the black vernacular during his speech at the eviction: “They ain’t got nothing, they caint get nothing, they never had nothing” (279). As a result of this newfound comfort with black cul- ture, Invisible Man achieves the confidence necessary for him to finally defend and assert himself, starting with his misguided dumping of a spittoon on a man who resembles Bledsoe (257). Invisible Man also stops concerning himself with how other people view him — in other words, he actually frees himself of Du Boisian double-consciousness — as he shows by unabashedly consuming four sweet yams out in the busy streets of New York City: “I no longer felt ashamed of the things I had always loved . . . . What and how much had I lost by trying to do only what was expected of me instead of what I myself had wished to do?” (266). While staying at Mary’s, Invisible Man is no longer of the Washingtonian mindset and is finally comfortable being himself and making his own decisions, suggesting that Ellison offers hope for resolution only in a shameless acceptance of one’s roots and abandonment of Washington’s duplicitous roadmap for blacks’ success as he set forth in Atlanta. Thus, as Jesse Wolfe has suggested, Ellison’s critique of Du Boisian double-consciousness lies not in a direct opposition to the concept but rather in an implicit difference; whereas Du Bois describes double-consciousness as irreconcilable, Ellison offers a glimpse at resolution (Wolfe 624). However, it is not long after Invisible Man makes his marked leap in embracing his roots and reconciling his persistent duality that he gets involved with a communist-like organization whose sole purpose is to suppress individuality and any acknowledgement of culture or difference. Just as it seems that Invisible Man rejected the practice of Washingtonian appeasement, he is asked to dive back into the role. Brother Jack, one of the principal white members of the Brotherhood trying to recruit Invisible Man, literally asks him, “How would you like to be the new Booker T. Washington?” (IM 305). Furthermore, as literary critic Houston Baker suggests, Ellison explicitly draws a connection between the paternalistic white trustees of the Institute and the members of the Brotherhood when another white member of the movement comes up to Invisible Man and asks him to sing a spiritual “or one of those real good ole Negro work songs” (qtd. in Baker 2). Though his conscience advises him against joining the organization — “I looked at them, fighting a sense of unreality... this was real and now was the time for me to decide or to say I thought they were crazy and go back to Mary’s” (308) — the protagonist finds himself compelled to prove amenable to Brother Jack’s demand. However, this time he unsuccessfully attempts to follow his grandfather’s deathbed advice on dealing with whites: “live with your head in the lion’s mouth ... overcome ’em with yeses, undermine ’em with grins, agree ’em to death and destruction, let ’em swoller you till they vomit or bust wide open” (16). Conflicted, Invisible Man both 27 28 accepts and denies his role as the new Booker T.: “To hell with this Booker T. Washington business. I would ... be no one but myself ... They may think I was acting like Booker T. Washington; let them. But what I thought of myself I would keep to myself” (311). Invisible Man believes he has made progress. In abandoning all hopes of returning to the Institute, he believes he has left behind his enslavement to Washington’s accomodationism. Likewise, in enjoying himself at Mary’s, he believes he has also reconciled the Du Boisian double-consciousness. Unfortunately, Invisible Man has underestimated the power of his predecessors’ ideas. Because he has no clear, distinct vision from them, he cannot simply “act like Booker T.” Under this pretense, he unknowingly slides right back into the role and mindset prescribed by Washington and quickly becomes the passive pawn he swore he would not be. Perhaps Ellison’s most painful and forceful critique of both Washington’s obedient demeanor toward whites and, more pointedly, Du Bois’s demand for militant protest is manifested through his inclusion and analysis of the Harlem riot. While looking upon the scene of chaos and destruction, Invisible Man at first believes the blacks engaging in the escalating “race riot” to be consciously risking their lives in hopes of effecting change to help defeat the white power structure. However, he soon realizes that they are actually reinforcing the white power structure by contributing to the devastation of their homes and workplaces, an act that precipitates their own disempowerment. As he reflects on the events following the death of his former Brotherhood colleague and friend, Tod Clifton, he comes to the haunting realization that the slaughter occurring before him “was not suicide, but murder” (553), “planned” by malicious and propaganda-crazed members of the Brotherhood who were extremely cognizant of what they were doing. Realizing he has been a blind “tool” for the Brotherhood this entire time — no freer than one of Clifton’s Sambo dolls — Invisible Man is dumbfounded at his role in the bloodshed. Through Invisible Man’s realizations and actions leading up to and during the riot scene, Ellison poignantly illustrates how violently imprudent and blind militancy can be. Thus, while Ellison doesn’t specifically reject the organized and guided use of aggressive force that Du Bois suggested in agitating for black rights, he does expose the dangers of spontaneous or imprudent violence — namely the possibility that it can destroy black people rather than uplift them. Just as Invisible Man’s impulsive assertiveness resulted in his abusing a guiltless black reverend at the Men’s Club rather than Dr. Bledsoe, the riot towards the end of the novel results in violence, destruction, fragmentation, and homelessness for many innocent Harlemites. Because they fall victim to the misguided militancy of Ras the Destroyer, the leader of a militant black nationalist movement opposing the Brotherhood, the people of Harlem inadvertently participate in a plan which benefits the white-controlled Brotherhood, as Invisible man finally realizes: “Could this be the answer, could this be what the committee had planned, the answer to why they’d surrendered our influence to Ras? ... I could see it now, see it clearly and in growing magnitude ...The committee had planned it” (553). However, Ellison does not just blindly criticize Washington and Du Bois without offering his own hope for blacks. Though the direction Ellison proposes for black Americans is not explicitly spelled out, it is clear in those moments and speeches in which Invisible Man relinquishes control to his subconscious emotions and allows himself to truly acknowledge his own thoughts. The first cogent example of this occurs during the protagonist’s first official speech for the Brotherhood, prior to his four-month-long brainwashing. After being scolded by Brother Jack for speaking about his individual background, Invisible Man proclaims that “silence is consent,” overtly condemning Washington. Then, in a revelatory moment, he falls into a “husky whisper”: “I feel suddenly that I have become more human .... Not that I have become a man, for I was born a man. But that I am more human. I feel strong, I feel able to get things done! I feel that I can see sharp and clear and far down the dim corridor of history and in it I can hear the footsteps of fraternity” (346). Thus, by emphasizing the clarity and power associated with thinking as a human being rather than a black man or an American, Ellison calls for black Americans to think likewise and thus empower themselves. And, though Invisible Man is lambasted by many of the Brothers for the content of his speech, he admits, “I meant everything that I had said to the audience, even though I hadn’t known that I was going to say those things .... I had uttered words that had possessed me” (353-4). In fact, it is this very quality of a “visceral voice” that makes it so Through Invisible Man’s realizations and actions leading up to and during the riot scene, Ellison poignantly illustrates how violently imprudent and blind militancy can be. Thus, by emphasizing the clarity and power associated with thinking as a human being rather than a black man or an American, Ellison calls for black Americans to think likewise and thus empower themselves. influential and genuine. At one point in Ellison’s drafts, when Mr. Treadwell, a guest at Mary’s boarding house who was omitted in the final edition, is telling a story, he recalls his recently deceased friend Leroy’s definition of what is considered human: “the capacity for experiencing raw emotions” (“Ralph Ellison Papers,” Box 142). Though Ellison left this out of his final version, it seems his definition was very much in line with Leroy’s. Thus by expressing Invisible Man’s most radical, interesting, and progressive views when he is possessed by his human emotions, rather than regurgitating national, political, or racial rhetoric, Ellison shows the importance of transcending race, nationality, and any other artificial grouping in favor of a common humanity. In fact, this common humanity is a pervasive theme through Ellison’s criticism of American literature in his collection of essays, Shadow and Act, as well. Arguing that American authors such as Hemingway have repeatedly engaged in “perhaps the most insidious and least understood form of segregation” by including “counterfeit” black characters in their novels who simply function as “racial clichés” denied the complexity of an individual, Ellison demands that Americans finally either take on issues of race in their entirety or quit masking and simplifying blacks (Shadow 35). The only way one can combat stereotypes and misunderstandings, Ellison argues, is through recognition of a common humanity and the interconnected nature of all Americans. Though specifically addressing writers, Ellison’s warning that those “who stereotype or ignore the Negro and other minorities in the final analysis stereotype and distort their own humanity” is directly applicable to all people (44). Ellison reiterates this message and equates individuality to humanity in Invisible Man’s other great and, importantly, extemporaneous speech at Tod Clifton’s funeral. Invisible Man begins by establishing Clifton’s individuality: “His name was Clifton and he was tall and some folks thought him handsome .... His name was Clifton and his face was black and his hair was thick with tight-rolled curls — or call them naps or kinks” (IM 455). He then goes on to tie Clifton to all humans and establish the link between individual being and all human beings: “Here are the facts. He was standing and he fell. He fell and he kneeled. He kneeled and he bled. He bled and he died. He fell in a heap like any man and his blood spilled out like any blood, wet as any blood .... That’s all” (456). In this way Ellison finally shows how individual differences —such as the color of one’s skin or one’s gender — should not be ignored in order to embrace humanity but rather acknowledged and honored. Thus Ellison offers his own hope for black Americans, one that is very distinct from both Washington and Du Bois. Through the actions of Invisible Man, Ellison not only presents the lethal impact of Washingtonian appeasement and cautions against blind militancy but also directly connects the self-defeating Du Boisian conflict of selves to the pursuit of Washingtonian success, as both are based on the idea that black Americans should define themselves by their race. Finally, through exposing his unique views in the emotional and visceral words articulated in Invisible Man’s various speeches, Ellison ultimately creates his own version of Washington’s Atlanta Exposition, one which neglects neither the black experience nor the American one but rather realizes the interconnectedness of the two. According to critic Kenneth Warren, Ellison always sought to place individual experience within a larger group context, whether ‘Negro,’ ‘American,’ or some combination of the two. In fact, Ellison’s larger point was that, had we the courage to admit it, the inescapable combination of the two was not only the truth of our individual experiences but also the inescapable implication of America’s founding documents. (172) In demanding that this combination be accepted and appreciated, Ellison puts forth an alternative possibility for black Americans to live productive lives, an alternative that offers hope and optimism for blacks by embracing that which makes them both individual and human. He thus connects black Americans with everyone else in a common humanity which can transcend the tensions, irreconcilable doubts, and prejudices of racism and nationalism and begin to resolve the conflicts perpetually plaguing America. ª Works Cited Baker, Houston A. “Meditation on Tuskegee: Black Studies Stories and Their Imbrication.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (1995): 51-60. Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Modern Library, 2003. Ellison, Ralph W. Invisible Man. 2nd ed. New York: Vintage International, 1995. Ellison, Ralph W. “Ralph Ellison Papers.” 1945. Ellison, Ralph W. Shadow and Act. New York: Vintage International, 1953. Warren, Kenneth W. “Ralph Ellison and the Problem of Cultural Authority.” boundary 2 30 (2003): 157-174. Washington, Booker T. Up from Slavery. Toronto, Canada: Dover Publications, Inc., 1995. Wolfe, Jesse. “‘Ambivalent Man’: Ellison’s Rejection of Communism.” African American Review 34 (2000): 621-637. 29