Sequential Choices and Partisan Transitions in U.S.

advertisement

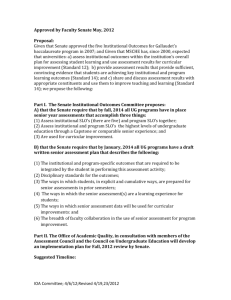

SequentialChoicesandPartisanTransitions in U.S. SenateDelegations:1972-1988 GaryM. Segura Stephen P. Nicholson Universityof California,Davis A recent increasein the numberof states sending mixed delegationsto the U.S. Senate, i.e., having one senatorof each politicalparty,has led scholarsto ask why essentiallystableelectoratesproducedifferent partisanoutcomes. We contend that the existing argumentsdo not, and cannot, adequatelyexplainthis phenomenon.The failureof these earlierattemptsis the directresultof a misinterpretationof the choices faced by voters in sequentialelections. The existence of mixed Senate delegationsis not all that extraordinaryin an era of candidate-centered,ratherthan party-centered,campaigns.In short, sequential,binarydecisionsarenot equivalent,and mixed delegationsareperfectlyconsistentwith general expectationsof voting behaviorand electoralpolitics.A model consistingof election-specificvariablesis used to predict transitionsto and from mixed delegations,and to directlytest, and reject,the primary existing explanation. EachCongresssince 1972has had 21 or more Senatedelegationswith one member from each party, and in the Ninety-sixth Congressthe number peakedat 27. We believe that this increasinglycommonphenomenondepictedin figure 1 is consistent withJacobson's(1990) observationof "a patternof electoraldisintegration" (7). He and others (Alesina and Rosenthal 1991; Cox and Kernell 1991; Fiorina 1992) have accumulatedan impressivebody of evidence that the electorateis increasinglylikely to abandonpartisanloyalties, express inconsistent preferences, and divide their votes. The Senate problem, as it has been conceptualized,is distinct from the more generalquestionof dividedgovernmentin two importantways. First, except in the rarestof instances,delegationsare elected sequentially.When explainingdivided government,we examinea single pool of votersmakingmultiple, and inconsistent, decisions on the same day. This simultaneitycreates an informationdeficit that can, at least in part,accountfor apparentlyinconsistentbehavior.The electionof a An earlierversion of this articlewas deliveredat the 1992 annualmeeting of the AmericanPolitical Science Association,The PalmerHouse Hilton, Chicago,Sept. 3-6, 1992. The authorswish to thank the discussants,Dan Palazzoloand David Rohde, for their thoughtfulsuggestions.In addition,helpful comments were offered by Bob Jackman,Ross Miller, Randy Siverson, and Scott Gartner,all of the University of California,Davis. Gloria Cornette,of the Citizens'ResearchFoundationof the University of SouthernCalifornia,was helpful in providingearlycandidateexpendituredata.Researchassistance was providedby JenniferBrustromand her help was greatlyappreciated. Vol. 57, No. 1, February1995, Pp. 86-100 ? 1995by the Universityof Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819 THE JOURNAL OF POLITICS, 7 SequentialChoicesand PartisanTransitions8 FIGURE 1 NUMBER OF MIXED DELEGATIONS: 1948-1988 28 26. 24 22 4f1 20 18 16 0l Z 14 12 10 8 1945 - 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 Year Senate delegation,however,occurs in two iterations.Voters have informationregardingthe outcomeof the other raceincludingthe partypreferenceand behavior of the other senator-information that they lack when multiple elections are held simultaneously,where all resultsare uncertain. Second, explanationsthat focus on the variancein the populardemandsassociatedwith particularinstitutionsarenot helpfulin explainingtransitions.Jacobson's (1990) observationsregardinghow expectationsof the citizenry differ from the House to the presidencycan account for behavioralvariancein voting decisions acrossbranches.But sequentialdecisionspertainingto Senateelectionsare,on this issue, essentiallythe same-institutional expectations,therefore,should not vary. decisionsmadeby The divided Senate delegation,then, results from inconsistent An betterinformedvotersunderidenticalinstitutionalcircumstances.' answer, then, 'One possibility is that demographicchanges in the electorate are driving transitions. If so, we shouldobservemorefrequenttransitionsto mixeddelegationsafterfour-yearintervalsratherthantwo- 88 GaryM. Seguraand Stephen P. Nicholson may provide importantinsights into the causes of divided government.We argue that existing explanationsof this phenomenonbased on voter characteristicsare unsoundand resultfrom incorrectassumptions.We offer an alternativemodel that predicts transitionsto and from mixed delegationsthat is built strictly upon the politicalcharacteristicsof each race. Our results lend strong supportto Jacobson's (1990)explanationof electoraldisintegrationundermoreconstrainedcircumstances. EXISTING APPROACHES StrategicCitizen.The first approach,which we call the strategiccitizen model, has been proposedby a numberof scholars(Alesina,Fiorina,and Rosenthal1991; Fiorina 1992). The strategiccitizen model begins with the recognitionthat Senate electionsare a serialprocess.There is a sitting senatorwho is not facingthe voters at the time of the election.2A criticalnumberof citizens, it is argued,recognizethat representationin the Senate is accomplishedthrough two delegates rather than one. Ratherthanbeing concerned,then, aboutthe ideologicaltenor or partisanship of each senator,voters "mayvery well care about the total representationof their state in the Senate"(Fiorina 1992, 83) and seek a delegationthat, as a whole, approachesa moderateideologicalideal point. As in figure2, if the sitting senatorlies to one side of the ideal point, the strategic citizen will vote for the currentcandidatewho is closest to being as far fromthe mid-point as the sitting senator, but on the opposite side. Alesina, Fiorina, and Rosenthal(1991, 9) call this tendency the "oppositepartyadvantage,"since, in all but the rarestinstances,that candidatebest able to "balance"the sitting senatoris from the opposingparty.The idea is that the resultingdelegation'sideologicalmix will approximatethat of the strategiccitizen. This model is built upon three assumptions:(1) the median voter's ideal point lies between the sitting senator'sand the candidate'sof the opposite party;(2) the candidatefromthe oppositepartyis fartherfromthe sitting senatorthan the candidate from the senator'sown party;and (3) the state ideologicaldistributionis more or less normal.If any of these three assumptionsareviolated,the findingof an "opposite party advantage"is likely wrong. In fact, this erroramounts to little more than a failureto conceptuallydistinguishthe nationalpartisandichotomyfrom the ideologicalcontinuumwithin a state. Empirical support for this "advantage"is weak at best (Alesina, Fiorina, and Rosenthal 1991), having a significanteffect only for incumbentsand only in allowingfor more change-and subsequent"corrections"to unifieddelegationsaftertwo years,reflecting enduringpopulationchanges.Of the 165 validtransitionsbetween 1948and 1988,91 tookplacetwo yearsor less since the electoratelast exhibiteda senatorialpreferencefor the oppositeparty,while only 74 took place after the longer intervalof four years.That transitionsare more likely to occurafteronly two years(or less) suggeststhat demographicchangesand their politicalimplicationsarenot drivingthe creationof mixed delegations. 2Fromthis point, the term sittingsenatorwill alwaysreferto the memberof the Senate notrunningifl the currentelection. For membersparticipatingin the election in question,the term will be incumbent. SequentialChoicesand PartisanTransitions 89 FIGURE 2 STRATEGIC CITIZEN MODEL'S DISTRIBUTIONAL ASSUMPTIONS DC M RC RS DC-Democratic CandidateIdeologicalPlacement RC-Republican CandidateIdeologicalPlacement M-Population Mean IdeologicalIdealPoint RS-Republican Sitting SenatorIdeologicalPlacement presidentialelectionyears.3But more importantly,to the extent that this "opposite partyadvantage"exists, it is more a descriptionof an aggregate-levelempiricalregularitythan an ex ante factorthat contributesto the individualvotes which are collectivelyproducingthese outcomes.While Fiorina(1992) laterstipulatesto the "as if" characterof this model, such a stipulationis insufficientwhen drawinginferences about individual behavior based on collective, occasional,regularities.In short, the dataand analysisemployedin existing researchdoes not providea plausible nexus between the political dynamicsdescribedand the individualbehavior necessaryto producethese outcomes. The most seriousobjectionofferedto the strategiccitizen model is the portraitit paints of the Americanvoter. The strategicbehaviordescribedrequires:(1) that a crucialsegmentof the electoratepossessesa largeamountof informationconcerning the ideologicaltendenciesof the sitting senator,both candidates(includingany incumbent), and their own preferences;(2) that citizens can accuratelyevaluate this informationand calculatewhich of the availablechoices would produce the ideologicaloutcome most desired; and (3) that citizens act on these evaluations by voting for a candidatefurtherfrom their own position in hopes of achievinga 3This finding is not surprisingand might well be an artifactof the politicaltrends in the executive branch.In 1965, Democratsheld 26 unified delegationsand sharedin 16 mixed delegations,while in 1985 they held only 12 unifieddelegationsand sharedin 23 mixed delegations.Over the same interval, Republicanswon 4 of the 5 interveningpresidentialelections.We fully expect, then, that in presidential election yearswhen incumbentsare running,a disproportionatenumberof losers (or less than impressive winners)were Democratsrunningin stateswherea Democratheld the other seat. 90 GaryM. Seguraand Stephen P. Nicholson long-run strategicoutcome. This model predicts a significantnumber of citizens voting for both the sitting senatorand his or her ideologicalopposite. We arguetwo points in responseto this portraitof the strategicvoter. First, the model actually underestimates the demands made on the citizenry because it assumes that citizens are interestedin the ideologicalcast of their Senate delegations but not in public policy outcomes.It is more reasonableto believe that policy is the centralconcern of informedcitizens. When attemptingto cast optimal votes, the strategiccitizen is concernedaboutproducinga policy-makingapparatusthat will, in turn, produceoutcomesclosest to his or her ideal point. A state delegationthat mirrorsone's ideologicalpreferenceis of little comfortto the informedvoter when that delegationis partof a largerpoliticalstructurethat consistentlyproducespolicy in conflictwith that preference. Fiorina (1992) recognized this point when developing his explanationfor divided government.His "modelof policy balancing"(Fiorina80) is premisedon the notion that citizens are outcome-driven,and they recognize the input of both elected branchesto those outcomes.4Curiously,Fiorina and his colleaguesopt to exclude both the outcomeorientationand the role of the other elected branchesin the processfrom their model of Senatedelegations.5 To assume that citizens are outcome-focused,ratherthan concernedonly with the ideologicalbent of their state's delegation,makes the strategicvoting model considerablymore complex. In addition to balancingthe influence of the state's other senator,this highly sophisticatedvoter would have to evaluateother political actors:the likelyideologicalcomplexionof the House of Representatives,the occupant of the White House, and the remainingmembers of the Senate. However, these evaluationsoccur in an information-poorenvironmentsince the determination of the entire House, one third of the Senate, and occasionallythe president,is simultaneous.As seen in figure 3, a moderatevoter would be well advisedto vote for GOP Senate candidatesin both elections if that voter anticipatesa heavily DemocraticHouse, Senate, and a Democraticpresident. In short, when we shift our focus from the individual state's Senate delegation to policy outcomes, the strategiccitizen model of ideologicalbalancingrequiressubstantiallygreaterinformationand evaluativeskills from voters.6 Though this work sees voters as interestedin "a balancedexecutive-legislative package"(Alesina, Fiorina, and Rosenthal 1991, 29) a policy-outcome focus is 4Alvarezand Schousen (1993) find little empiricalsupport for the policy-balancingexplanationof dividedgovernment. 5LikeFiorina,his colleagueshave demonstratedconcernfor outcomefocus and the role of all elected branchesin their determination,though againthis was broughtto bear on the generaldivided government question and not the specific problemof Senate delegations.See Alesina and Rosenthal(1991). 61t is importantto point out that a shift in emphasisto policy outcomes yields expectationsthat are fully consistent with the existence of mixed delegations.Single-issue voting is, we have argued,more likely than the complex ideologicalcalculationsproposed.Since issues vary in saliencyover time, and issue majoritiesare seldom congruent,we should fully expect that sequentialissue-orientedelections would yield politicallyinconsistentoutcomes. 91 SequentialChoicesand PartisanTransitions FIGURE 3 DISTRIBUTIONAL ASSUMPTIONS, ENHANCED EXPECTATIONS, AND POTENTIAL OUTCOME DISTORTIONS IN THE STRATEGIC CITIZEN MODEL M DC RC RS P HR S DC-Democratic CandidateIdeologicalPlacement RC-Republican CandidateIdeologicalPlacement M-Population Mean IdeologicalIdealPoint RS-Republican Sitting SenatorIdeologicalPlacement HR-House of Representatives'AnticipatedMean IdeologicalPlacement P-President's Anticipated(or estimated)IdeologicalPlacement S-Senate's AnticipatedMean IdeologicalPlacement consideredonly in a simple test to see if the partisancomposition of the entire Senate is significantlyrelatedto the aggregateresults (it is not). The presidencyis addressedonly in a midtermdummyvariable,and the House is ignoredaltogether. Our secondpoint is that the model'sexpectationsof the electoratedo not fit well with what we know about the abilities and behaviorof the Americanvoter (e.g., Converse1964 amongnumerousothers).Moreover,when our objectionsconcerning the need for an outcome focus are takeninto consideration,furtherraisingthe cognitiveand informationaldemandson the votersin question,the model becomes even more implausible. Two Constituencies.The second generalexplanationis commonlyknown as the two constituenciesthesis (Fiorina 1974;Bullock and Brady 1983; Shapiro,Brady, Brody, and Ferejohn1990).Essentially,this argumentassumesthat each senatoris elected by differentcoalitionsof voters, and it is to these specificcoalitionsthat the senatorrespondswhen makingpolicy decisions.The assumption,of course,is that each party enjoys about the same generalstrengthin the populace,againmore or less normallydistributed.Each senatormodifieshis positionsonly slightly, falling generallybetweenthe ideal points for their coalitionand the medianvoter position. This slight shift allows the senatorto maintainhis or her party'sbase of support, 92 GaryM. Seguraand Stephen P. Nicholson and simultaneouslyto appealto that small marginof voters aroundthe state mean to providethe necessarymarginof victory. Unlike the strategiccitizen model, this approachmakesno unrealisticassumptions aboutthe level of informationor cognitiveabilitiesof voters.Also, this model anticipatesonly a smallmarginof nonideologicalswitchers,ratherthan the significant oscillationof sophisticatedvotersimpliedby the strategiccitizen model. The two constituenciesthesis offers an explanationof electoralinstabilitybuilt upon the existenceof two capableand competitivecoalitions.However,it does not specificallyprovidea model of electoraloutcomes.We expect that the candidatesof both the sitting senator'spartyandthe oppositepartywill adoptpositionsintended to maintainpartysupportand to appealto the medianvoter.Absentthe advantages of incumbency,thereis no reasonto assumethatthe candidateof the oppositeparty is any more likely to win median voters than the candidateof the sitting senator's party.This model, therefore,canexplainneithertransitionsto and frommixeddelegations,nor when-under these electoralconditions-mixed delegationswill exist. We offer an explanationof transitionsthat is not reliantupon, but is consistent with, a two-constituenciesportraitof the electorate. RETHINKING THE PROBLEM The two-constituencies thesis and the strategic-voterthesis are attempts to explain apparentlyinconsistent choices made under identical circumstances.Of course, institutionallydrivenexpectationsof senatorsshould not vary,and, ceteris paribus,votersshouldbehaveconsistentlyin electingtwo people to the sameoffice. Sequentialchoices in Senate elections are not, however,identical.In fact, given the increasingdisintegrationof electoralpolitics, sequentialSenate elections are of eachraceareimportantandmay decreasinglyrelated.The politicalcharacteristics varywidely acrosselections.While voters'policy preferences,expectationsof senators,and partisanshipmay not changeappreciably,the binarychoice-the candidatesthemselves,theircampaigns,and the surroundingpoliticallandscape-change dramatically.In an eraof decliningpartisanshipand candidate-centeredcampaigns, these changesare of criticalimportanceto voters. Transitionsto and from mixed delegations,we argue,result directlyfrom the impactof these characteristics. In short, we believe that the emergenceand disappearanceof mixed delegations can be explainedby specific politicalcircumstances,are neither extraordinarynor unpredictable,and are not the resultof unrealisticallysophisticatedbehavior. POLITICAL FACTORS FACILITATING TRANSITIONS Using all regularlyscheduledSenate elections from 1972 to 1988,7and building on the workof Abramowitz,Jacobson,Squire,and others,we offera model built on 7One election, the 1976 Virginiaelection, is excluded due to the presenceof an incumbentthat was not a memberof either majorparty.The election is not a transition.This reducesthe n to 299 and has no appreciableeffect on the results. SequentialChoicesand PartisanTransitions 93 long-identifiedpoliticalfactorsincluding four candidate-centeredvariables-candidatequality,short-termshocks,primaryelection results,and campaignexpenditures-and two contextual variables-political competitivenesswithin the state electorateand the electoralcycle. CandidateQuality.Jacobson(1990) arguesthat the qualityof the challenger,his or her political experience, affects the outcome of any given House election. Modest evidenceexists for a similareffect of challengerqualityon Senateoutcomes (Abramowitz1988) and in voter informationlevels and evaluationsin Senate elections (Squire 1992). We expect, then, that differencesin the qualityof candidates should be pivotalin predictinga transition.We arguethat the presenceof a highly qualifiedchallengermay be sufficientto providea victorymarginto the candidate of a partywith little historyof successin seekinga given seat. Using a modifiedversionof Squire's(1988) coding for previouspoliticalexperience as a measureof quality,we test for the impactof candidatequalitydifferences on the likelihoodthat an election will producea transitionin the partisancomposition of a Senatedelegation.8The relativequalitymeasureis the differencebetween the incumbent'sscore(or incumbentpartycandidate'sscore when the seat is open) and the challenger'spolitical experience score. The larger this difference, the smallerthe chancethat the election will result in a transition.By incorporatingincumbentsinto this scheme, we also accountfor the differencesthat may occur due to the absenceof an incumbentin open-seatelections.9 Short-TermShocks.The impact of political controversy,scandal,and reported health problems on the electoral fortunes of the incumbent party is well documented (Abramowitz1988). For example, a confession of alcoholismby Herman Talmadgein the 1980 Georgiarace and RogerJepsen's membershipin a "health spa" which was later closed for prostitutionbefore the 1984 Iowa contest were likely instrumentalin their defeats. For this reason, a dichotomous measure of short-termfactors affecting the quality of the incumbent party candidate,coded 8Squire'sscheme is: Governor-6; House Member-5; State Official-4; State Legislator-3; Local Office Holder-2; Other Political Position-1; no experience-0. Three changes were made. First, we chose to eliminatethe weightingsystem Squire uses to assess the value of running for Senate as an incumbentofficeholderwith an existing constituencythat is part of the new constituency.The resulting weights can give an enhanced,and we feel inappropriate,value to state offices such as treasureror insurancecommissionerover incumbentHouse members.Second, we attemptto accountfor public personalitiesseekingelectiveofficesince the namerecognitionassociatedwith their public personaeshould be figuredinto the measureof quality.Likewise, people less familiarto the electoratebut well experienced in electoralpolitics presenta difficulty.We have chosen to code the astronauts,the notoriouscollege president,and the authorin the data, as well as formergovernorsand senatorsfrom neighboring states,as threes,tryingto accountfor unusuallyhigh namerecognitionin the firstfour instancesand the high degree of politicalexperiencein the lattertwo. Likewise, a formerpresidentialadviserand U.N. ambassadorwas also coded as a three. Finally, since our ultimatemeasureis comparative,we include incumbentsand code them as sevens. 9Informationon the politicalexperienceof each candidate,as well as scandalsand controversiesbeQuarterlyWeeklyReportelecsetting incumbentpartycandidates,was obtainedfrom the Congressional tion roundupfor each year. 94 GaryM. Seguraand Stephen P. Nicholson one for the presenceof politicalproblems,controversies,or health issues and zero in their absence, has been included and should be a positive predictorof transitions. Informationregardingthe presenceof these factors-disastrous campaigns for president, indictments,allegationsof improprieties,etc.-was obtainedfrom the Congressional Quarterly'spreelectionroundupswhich include descriptionsand detailsof each race. Primaries.A transitionin the partisancontrol of a Senate seat should be more likely if the incumbentpartyis divided in its selectionof a candidate.Divisive and hotly contested primarycontests are apt to reveal candidateor incumbentweaknesses, highlightissues likely to splinterthe incumbentparty'scoalition,and drive down the eventualturnoutamongthe incumbentparty'svoters duringthe general election(Abramowitz1988;Kenney and Rice 1984).For this reason,the percentof the primaryvote receivedby the incumbentparty'snominee is included as a predictorof transitions,with the likelihoodof transitionincreasingas the primarypercentagefor the incumbent(or incumbentpartynominee)decreases.'0 CandidateFinances.The impact of money on congressionalelections is well documented(e.g., Fenno 1982;Sorauf 1988;Jacobson1980, 1990, 1992). A better financedchallengerpresentsa more formidableobstacleto the reelectionof any incumbent, and likewise should present the best opportunityfor a transitionin the partisancompositionof a state'sSenatedelegation. For each Senateelectionfrom 1972-1988, we recordedthe total funds dispersed by each majorpartycandidatewho reachedthe generalelection, as reportedto the Federal Elections Commission.As the ratio of challengerspending to incumbent spending (or spending by the incumbent party's candidate)increases,we expect that the likelihoodof a transitionto or from a mixed delegationwill also increase." l PoliticalCompetitiveness. Significantattentionhas been given to the politicalheterogeneityor homogeneityof statesas an importantfactorcontributingto national electoraloutcomes (Bullock and Brady 1983). This concept is at the heart of the two constituenciesexplanation. We use the absolutedifferencebetweenthe percentagesof a state'scongressional delegation held by each party as a measure of its political competitiveness.The measurecan take on a value from zero-meaning that each party holds the same number of seats in the state's House delegation-to one hundred-indicating a 101nthe absenceof a primary,either due to the lackof an opponentor a caucus/conventionsystemof nomineeselection,the incumbentpartynomineeis coded to have received100%of the vote. While this approachglosses over the possibilityof continuingdivision within the party,it is likely that the deleteriouseffects of such low saliencedivisionarelargelymitigatedin the absenceof directprimaryelections. IIThis calculationwas helpful in that it implicitlycontrolledfor state size, whereasa linearcombination of the two spending totals would have been problematic.The downside was the loss of two additionalobservations.In the 1976 Senate racein Wisconsin,Proxmirespent only $697 as comparedto his opponent's$62,210, producinga ratiothat was enormous.In 1982,he spent nothing(at leastas reported to the FEC), even while his opponentspent almost$120 thousand,makingthe valueof the financeratio undefined.This lowersthe valid n to 297. SequentialChoicesand PartisanTransitions 95 low degreeof competition,as evidencedby the completecontrolof that delegation by one party. To estimatethe relationshipbetween the competitivenessin the state electorate and the likelihood of transitions,we need to control for the composition of the existing Senate delegation.Dominationof the state by a single partyshould be directly related to the likelihood of a transitionif the challengeris of the state's majorityparty, and inversely related if the challengeris of the state's minority party.For this reason,we recoded the variable,multiplyingby -1 when the challenger is from the politicallydisadvantagedparty. This producesa politicalcompetitivenessvariablethat variesbetween -100 and + 100. Negative values indicate that the challengerbelongs to a partythat capturesonly a minorityof House seats and is thereforeless likely to win and producea transition;the converseis true for positive values. A value of 0 indicates that the parties show approximatelyequal strength in House elections.'2This variableshould be positively related to the probabilityof a transition,regardlessof the electoralcircumstances. ElectoralCycle.For whateverreason,the presidential/mid-termelectioncycle is well recognizedas a significantpredictorof any party'schances in a generalcongressionalelection (Campbell1960;Kernell 1977;Jacobsonand Kernell 1981;and Abramowitz1988). This cycle, therefore, should help explain transitionsto and frommixed delegations.The winningpresidentialcandidateshouldhelp his or her party win more votes for senatorthan the party might otherwiseexpect, and cost copartisansvotes duringthe mid-termelection. In an electorallycompetitivestate, those boosts and hindrancesmight accountfor enough variancein the vote to produce a transitionin the compositionof the state'sSenatedelegation. In the model presentedbelow, electoralcycle is a dichotomousvariablecoded as follows:presidentialelection year when challengerparty'spresidentialnominee wins-i; presidentialelection year when challengerparty's presidentialnominee loses-0; midterm election year when the challenger'sparty is in opposition-i; midtermelection year when challenger'spartycontrolsthe White House-0. Electoralcycle should be a positive predictorof transitionssince it takeson the valueof one when the outpartyis advantagedby the electoralcycle. TESTING AND RESULTS We estimatetwo models-a model of transitionsin generaland one that considers the partisan composition of the delegation before the election-thereby specificallytesting the strategiccitizen model. The dependentvariableis a dummy variablecoded 1 when an election leads to a partisanchangein the compositionof the delegationto mixed or unified (indicatinga defeat for the incumbent party) 12Certainlyother measuresof partycompetitionare available.This particularmeasurecapturedour interest in each party'sability to win elections to Congresswithin each state. Though small states are prone to extremevalues, there is sufficientvariancein the dependentvariable-even at these extreme values-that no distortionresults.Analysisof the residualsalso yields no evidenceof heteroscedasticity. GaryM. Seguraand Stephen P. Nicholson 96 TABLE 1 LOGIT RESULTS FOR DELEGATION TRANSITIONS IN U.S. SENATEELECTIONS:1972-1988 Predictor Predictor Constant Candidatefinances Candidatequality Short-termshocks Chi-square Significance % Predictedcorrectly N = 297 .469 (.730) 2.57*** (.439) -.065 (.073) 1.77*** (.560) Primaryvote Electoralcycle Politicalcompetitiveness -.052*** (.009) .961** (.377) .526* (.320) 146.63 .0000 84.2% *Significantatp < .05; **significantatp < .01; ***significantatp < .001. and 0 when the election has no effect on the partisanshipof the delegation.'3The resultingnumberof cases, from 1972to 1988, is 297 elections. PredictingTransitions We test the impact of six variables,'4candidate-centeredand contextual,using logit analysis.The unit of analysisis the individualregularlyscheduledSenatecontest.'5Table 1 presentsthe resultsfor the model. 13Thereis one case, Minnesotain 1978, wherethe electionresultsin the seat changinghandsbut, due to a simultaneouschangein the otherseatvia a specialelection,the delegation'sstatusas unifiedremains unchanged.Though here the electoratechose two senatorsof the same party,this case is still coded as a transitionsince a seat changeshands. Coding it as a nontransitionor eliminatingthe case altogetherdo not fundamentallyalterthe substantiveinterpretationof the findings. 140ne variablenoticeablymissing from the model is whetheror not the incumbentis a candidatefor reelection.Transitionsare approximatelytwice as likely in open-seatelections when we controlfor the relativefrequencyof each type of election. We consideredincludingthis variablein the model but did not for both conceptualand methodological reasons.Since qualityis measuredas the differencebetweencandidates,and incumbencyis partof this measure,inclusionof a second variablemeasuringessentiallythe same thing wouldbe redundantlikely resultingin multicollinearityproblems.Also, its inclusioncontaminatesthe resultsfor other candidate-centeredvariables.The reasonis simple:as borneout in a one-wayanalysisof variance,the mean quality differenceis more than three times largerin elections contested by incumbents.Similarly,in races in which there was no incumbent,the ratio of challengerspending to incumbentpartyspending was more than twice that of racesin which there was an incumbent. Including open seats and challengerquality, instead of our comparativequality measure, has no significantimpacton the predictivepowerof the model nor the significanceof any of the remainingpredictors. "5Withthe exceptionspreviouslynoted. SequentialChoicesand PartisanTransitions 97 The results of the logit routineare highly consistent with our expectationsand the model goodness-of-fittests easily meet the criterionfor significance.The percent of transitionscorrectlypredictedis 84.2 with the model performingsomewhat better at predictingfailuresthan successes, as expected given the inherentlylarge stochastictermassociatedwith these outcomes.The resultssupportour contention that political variables,both candidate-centeredand contextual,can help explain transitionswithoutresortingto sophisticatedvoter models. Candidate-centeredvariablesare central to our explanationand are significant predictorsof the probabilityof transitions.The variableCandidateFinances,critical to the candidate-centeredage of politics, is highly significantbeyondthe .001 level. The sign of the coefficientis positive which suggests that as the ratio of spending increasesbetweenchallengerand incumbent,the probabilityof a transitionis more likely.In most of the casesin which transitionsdid not occur,the ratioof challenger spendingto incumbentspending was small (mean = .47). In contrast,the average ratio of spending in elections where transitionsoccurred was greater than one (mean = 1.40). Thus, when a transitiontakesplace, the challengeris likely to have spent moremoney than the incumbent(or the candidateof the incumbent'sparty). Two other candidate-centeredvariables,PrimaryVoteand Short-TermShocks, are importantpredictorsin our model. Both exceed the .001 significancelevel and the signs of their coefficients are in the predicted direction. The sign of the coefficient for Primary Voteis negative, suggesting that the greaterthe level of competitionan incumbent(or incumbentpartycandidate)facesin the primary,the greaterthe probabilitythe candidatewill lose. The coefficientof the variableShortTermShocksis positive indicatingthat politicalcontroversies,scandals,and health concernsadverselyaffect an incumbent'slikelihoodof reelectionand, in this instance,transitions. Interestingly,we find no supportfor the impactof CandidateQualityon transitions. Althoughthe sign of the coefficientis negative,it is far from achievingstatistical significance.Although we can only speculateas to the reasonswhy candidate quality did not affect transitionelections, these results might be attributedto the relativelylargerstakesinvolvedin Senateelections.The high profileof Senatecandidatesmay compensatefor the low name recognitionand inexperiencedelectioneeringwhich dooms many "low quality"House candidates.'6 The contextualvariablesare importantpredictorsin the model as well. As expected, the variableElectoralCycleis highly significantbeyondthe .01 level and the sign of the coefficientis positive. Therefore, if challengersare either of the same party of a strong presidentialcandidate,or of the opposite party of an unpopular 16Analternative,of course, would be to use challengerqualityas a predictor.We chose our measure becauseof its comparativenature,which accountsfor incumbencyand open seats. When substituted, challengerqualityperformslittle better than our CandidateQualityvariable,similarlynever achieving significance,and adds nothing to the predictivepowerof the model. Multicollinearityis not a problem.This variablesignificantlycorrelateswith only the Financevariable, and then only at r = -.2475, well below the generallyacceptedlevel of tolerance. 98 GaryM. Seguraand Stephen P. Nicholson president at the midterm election, they may have an advantage.Political Competitivenessis significantat the .05 level and the sign of the coefficientis in the hypothesized direction. This result suggests that the dominance of a state by the politicalpartyopposite the incumbentmay increasethe probabilityof an electoral defeat,and thereforea transition. Transitions to andfromMixedDelegations-A Testof the "Opposite PartyAdvantage" Evidencein supportof our alternativemodel is strong. Relianceon simple, and well-established,contextual,and candidate-centeredpoliticalvariablesallowsus to correctlypredict 84.2% of all transitions(incumbentparty defeats), both to and from mixed delegations. We are interestedif the predictivepower remainsrobust when we control for whetherthe potentialtransitioncreatesa mixed delegationor signalsits demise.To investigatethis question, we add an additionalvariableto the model-Delegation Partisanship-which measureswhether the delegationbegins the election unified (coded 1) or mixed (coded 0).'7 The additionof this variableallowsus to testthestrategiccitizenmodeldirectly.If Alesina, Fiorina, and Rosenthal(1991) are correctin their finding of an opposite partyadvantage,then we shouldlogicallyexpect the coefficienton this new variable to be positive and significant,indicatingthat a unifieddelegationmakesan incumbent partyloss (and a transitionto a mixed delegation)more likely, given the electorate's alleged preferencefor the "oppositeparty." Similarly,the presence of a mixed delegationwould reducethe likelihoodof an incumbentdefeatand a transition. Our findingsarepresentedin table2. The parameterestimate for DelegationPartisanshipis insignificantlydifferent from 0, lending supportfor our contentionthat the partisanshipof the other senator is of no consequence-in either direction-to the outcome of the election at hand. Moreover,the inclusionof DelegationPartisanshipcausesvirtuallyno change in the sign, magnitude,or significancelevels of the estimateson the originalvariables (the sole exception being the competitivenessvariablewhose p-value falls a fractionto .053). The additionalvariablehas little effect on the predictivepowerof the model since the percentpredictedcorrectlyremainsa robust83.8%. But werethe parameterestimatereportedin table2 to havereachedsignificance,it would still provideno supportfor the strategiccitizenmodel since the sign is in the wrongdirection.Whatlittle relationshipexists seemsto indicatethatthe probability of a transitionis higherwhen sucha transitionwouldresultin a unifieddelegation.In short,wefind absolutelynosupport for theexistenceof an oppositepartyadvantage. 17Analternativeapproachwould be to divide the populationinto two subsamplesand test the consistency of the model's performanceacrosstypes. We performedthis task and the results were generally supportive,the model accuratelypredicting87.4% of outcomes when the delegationbegins the cycle unified, and 83.2% when the delegationenters the election mixed. The method we choose to present here is somewhatmore elegantand helpful in that it allowsus to test an additionalhypothesis. 99 SequentialChoicesand PartisanTransitions TABLE 2 LOGIT RESULTS FOR DELEGATION TRANSITION IN U.S. SENATEELECTIONS:1972-1988 Predictor Predictor Constant Candidatefinances Candidatequality Short-termshocks .657 (.764) 2.58*** (.443) -.058 (.074) 1.84*** (.629) Primaryvote Electoralcycle Politicalcompetitiveness Delegationpartisanship -.053*** (.009) 1.00** (.384) .516 (.323) -.332 (.379) 147.52 .0000 83.8% Chi-square Significance % Predictedcorrectly N = 297 atp < .01; ***significantatp < .001. *Significantatp < .05; "*significant CONCLUSION Transitions are not surprisinggiven the highly competitive nature of Senate elections in the candidate-centeredera. In particular,challengerfinancinghad a greatimpact on the probabilityof a challenger'ssuccess, and is a criticalfactorin determiningthe probabilityof a transitionin either direction.Consistentwith the findings of Abramowitz(1988), improprietiesare found to make transitionsmore likely. Focusing on primaries,we find that an incumbentfacing seriousopposition will be less likely to overcomeintrapartydivisivenessin a generalelectionwhich, in turn, may well triggera transition.Finally, contextualvariables,includingboth the election cycle and state political competitiveness,are significantpredictorsof the probabilityof transitions. Yet we find no supportfor the "oppositepartyadvantage."The partisanshipof the other senatorhas no significantimpacton the probabilityof incumbentdefeat, substantiallyundercuttingthe validityof the earlierproposition-that some voters have a preferencefor mixed delegationsthat results in their increasedfrequency. The strongresultsof our predictors,especiallythe candidate-centeredvariables, offer a uniqueinsightinto the causesof dividedgovernment.As previouslyargued, the mixed Senate delegationquestion has been viewed as more of an enigmathan dividedgovernmentsince voter decisionsare (1) made sequentiallyfor (2) identical officesby (3) identicalconstituencies. We have broughtto this questionJacobson's(1990) hypothesisof "electoraldisintegration,"arguingthat outcomes of sequentialSenate elections in a candidatecenterederaare largelyunconnected.Our model successfullypredictsinconsistent outcomesacrossa set of decisionsmadeby votersoperatingwith substantiallyfewer 100 GaryM. Seguraand Stephen P. Nicholson uncertainties.In this context, the "electoraldisintegration"hypothesis operates in a more demandingconceptualenvironmentthan the more generaldivided government question. Our results, then, serve as importantadditional support for Jacobson'stheory. Manuscriptsubmitted22 November1993 received6 May 1994 Final manuscript REFERENCES Abramowitz,Alan I. 1988. "ExplainingSenate Election Outcomes."AmericanPoliticalScienceReview 82:385-403. Alesina,Alberto,MorrisP. Fiorina,and HowardRosenthal.1991. "WhyAre There So Many Divided Senate Delegations?"Occasionalpaper,Centerfor AmericanPoliticalStudies, HarvardUniversity. Alesina,Alberto,and HowardRosenthal.1991. "A Theory of Divided Government."Typescript. Alvarez, R. Michael, and Matthew M. Schousen. 1993. "Policy Moderationor ConflictingExpectations?Testing the IntentionalModels of Split-TicketVoting."AmericanPoliticsQuarterly21:410-38. Bullock, CharlesS. III, and David W. Brady. 1983. "Party,Constituency,and Roll Call Voting in the U.S. Senate."LegislativeStudiesQuarterly8:29-43. Campbell,Angus. 1960. "Surge and Decline: A Study of ElectoralChange."PublicOpinionQuarterly 24:40-62. Converse,Philip E. 1964. "The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics."In IdeologyandDiscontent, ed. David E. Apter. New York:Free. Cox, Gary W., and SamuelKernell. 1991. ThePoliticsof DividedGovernment. Boulder,CO: Westview. Fenno, RichardF. Jr. 1982. The UnitedStatesSenate:A BicameralPerspective.Washington,DC: American EnterpriseInstitute. Fiorina,MorrisP. 1974.Representatives, Roll Calls,and Constituencies. Lexington,MA: Lexington. Fiorina,MorrisP. 1992.DividedGovernment. New York:Macmillan. Jacobson,Gary C. 1980.Moneyin Congressional Elections.New Haven, CT: Yale UniversityPress. Jacobson,Gary C. 1990. TheElectoralOriginsof DividedGovernment. Boulder,CO: Westview. Elections.3d ed. New York:HarperCollins. Jacobson,Gary C. 1992. ThePoliticsof Congressional Jacobson,GaryC., and SamuelKernell.1981.StrategyandChoicein Congressional Elections.New Haven, CT: Yale UniversityPress. Kenney, PatrickJ., and Tom W. Rice. 1984. "The Effectsof PrimaryDivisivenessin Gubernatorialand SenatorialElections."journal of Politics46: 904-15. Kernell,Samuel. 1977. "PresidentialPopularityand NegativeVoting:An AlternativeExplanationof the MidtermCongressionalDecline of the President'sParty."AmericanPoliticalScienceReview71:44-66. Shapiro,CatherineR., David W. Brady,RichardA. Brody,andJohn A. Ferejohn.1990. "LinkingConstituency Opinion and Senate Voting Scores: A Hybrid Explanation."LegislativeStudiesQuarterly 15:599-621. Sorauf,FrankJ. 1988.Moneyin AmericanElections.Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman. Squire, Peverill. 1992. "ChallengerQualityand Voting Behaviorin U.S. Senate Elections."Legislative StudiesQuarterly17:247-61. Gary M. Segurais assistantprofessorof politicalscience, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA 95616-8682. Stephen P. Nicholson is graduatestudentin politicalscience,Universityof California,Davis, Davis, CA 95616-8682.