Atomic Bombings DBQ: Necessity & Ethics

advertisement

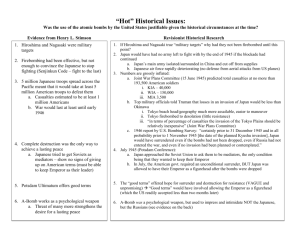

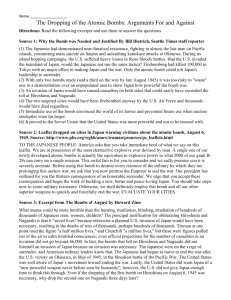

DBQ Using the documents and your own knowledge, evaluate the necessity of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Justify your answer. Document A: "I had then set up a committee of top men and had asked them to study with great care the implications the new weapons might have for us. It was their recommendation that the bomb be used against the enemy as soon as it could be done. They recommended further that it should be used without specific warning I had realized, of course, that an atomic bomb explosion would inflict damage and casualties beyond imagination. On the other hand, the scientific advisors of the committee reported that no technical demonstration they might propose, such as over a deserted island, would be likely to bring the war to an end. It had to be used against an enemy target. The final decision of where and when to use the atomic bomb was up to me. Let there be no mistake about it. I regarded the bomb as a military weapon and never doubted it should be used." President Harry S. Truman Document B: LEWIS STRAUSS(Special Assistant to the Sec. of the Navy) Strauss recalled a recommendation he gave to Sec. of the Navy James Forrestal before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima: "I proposed to Secretary Forrestal that the weapon should be demonstrated before it was used. Primarily it was because it was clear to a number of people, myself among them, that the war was very nearly over. The Japanese were nearly ready to capitulate... My proposal to the Secretary was that the weapon should be demonstrated over some area accessible to Japanese observers and where its effects would be dramatic. I remember suggesting that a satisfactory place for such a demonstration would be a large forest of cryptomeria trees not far from Tokyo. The cryptomeria tree is the Japanese version of our redwood... I anticipated that a bomb detonated at a suitable height above such a forest... would lay the trees out in windrows from the center of the explosion in all directions as though they were matchsticks, and, of course, set them afire in the center. It seemed to me that a demonstration of this sort would prove to the Japanese that we could destroy any of their cities at will... Secretary Forrestal agreed wholeheartedly with the recommendation..." Strauss added, "It seemed to me that such a weapon was not necessary to bring the war to a successful conclusion, that once used it would find its way into the armaments of the world...". quoted in Len Giovannitti and Fred Freed, The Decision To Drop the Bomb, pg. 145, 325 Document C: "The face of war is the face of death; death is an inevitable part of every order that a wartime leader gives. The decision to use the atomic bomb was a decision that brought death to over a hundred thousand Japanese. "But this deliberate, premeditated destruction was our least abhorrent alternative. The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki put an end to the Japanese war. It stopped the fire raids, and the strangling blockade; it ended the ghastly specter of a clash of great land armies. In this last great action of the Second World War we were given final proof that war is death." Secretary of War Henry Stimson Document D: "It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons. "The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children." - William Leahy, I Was There, pg. 441. Document E: Three days after the successful test blast, after consulting his advisers and Churchill (the British had cooperated in the project), Truman decided it would be wise to tell Stalin the news. Explaining that he wanted to be as informal and casual as possible, Truman said during a break in the proceedings that he would stroll over to Stalin and nonchalantly inform him. He instructed me not to accompany him, as I ordinarily did, because he did not want to indicate that there was anything particularly momentous about the development. So it was Pavlov, the Russian interpreter, who translated Truman's words to Stalin. I did not hear the conversation, although Truman and Byrnes both reported that I was there. In his memoirs, Truman wrote that he told Stalin that the United States had "a new weapon of unusual destructive force." Apparently, the President did not tell Stalin the new weapon was an atomic bomb, and the Soviet leader did not ask or show any special interest. He merely nodded and said something. "All he said was that he was glad to hear it and hoped we would make good use of it against the Japanese," Truman wrote. Across the room, I watched Stalin's face carefully as the President broke the news. So offhand was Stalin's response that there was some question in my mind whether the President's message had got through. I should have known better than to underrate the dictator. Years later, Marshal Georgi K. Zhukov, in his memoirs, disclosed that that night Stalin ordered a telegram sent to those working on the atomic bomb in Russia to hurry with the job. Charles E. Bohlen, Witness to History 1929-1969 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1973) pp. 247-248. Document F: During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of 'face'. The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude..." - Dwight Eisenhower, Mandate For Change, pg. 380 Document G: More and more of the injured come to us. The least injured drag the more seriously wounded. There are wounded soldiers, and mothers carrying burned children in their arms. From the houses of the farmers in the valley comes word: "Our houses are full of wounded and dying. Can you help, at least by taking the worst cases?" The wounded come from the sections at the edge of the city. They saw the bright light, their houses collapsed and buried the inmates in their rooms. Those that were in the open suffered instantaneous burns, particularly on the lightly clothed or unclothed parts of the body. Numerous fires sprang up which soon consumed the entire district. We now conclude that the epicenter of the explosion was at the edge of the city near the Jokogawa Station, three kilometers away from us. We are concerned about Father Kopp who that same morning, went to hold Mass at the Sisters of the Poor, who have a home for children at the edge of the city. He had not returned as yet By Father John A. Siemes, professor of modern philosophy at Tokyo's Catholic University Hiroshima- August 6th, 1945 Document H: Distance from Ground Zero (km) Killed Injured Population 0 - 1.0 88% 6% 30,900 1.0 - 2.5 34% 29% 27,700 2.5 - 5.0 11% 10% 115,200 Total 22% 12% 173,800 Document I: Distance from Ground Zero (km) Killed Injured Population 0 -1.0 86% 10% 31,200 1.0 - 2.5 27% 37% 144,800 2.5 - 5.0 2% 25% 80,300 Total 27% 30% 256,300 DBQ In 1945, The United States dropped two atomic bombs, one on Hiroshima and one on Nagasaki. Since, there has been much controversy on whether or not the droppings of these destructive bombs were necessary or not. Dropping the bombs was unnecessary. Some may argue that it ended the war and saved lives, but in reality the Japanese were already looking for a way to surrender as explained in Document D. We had already set up a sea blockade and successfully used other bombs against the Japanese. As seen in Document F, most believed that the Japanese were already looking for a way out of the war without losing face. One other reason that the bombs should not have been dropped is because the Japanese were not aware of its destructive power. In Document B, it proves that many scientists working on the bombs wanted to show Japan what it could do before throwing it at them. They suggested that they drop it somewhere where the Japanese could see it and its destruction. This might have been just as successful at scaring them out of the war. It’s sometimes said that one reason we might have dropped the bomb was to intimidate the Soviet Union, as implied in Document E. Truman had met with Stalin to tell him that he had a very powerful weapon. The United States knew that others were working to find an atomic bomb as well. It might have been that the U.S. just wanted to prove that they already had it and could use it against the Soviet Union. Had they not ended the war quickly, they might have had to enlist the Soviets help under conditions that might make them a more power nation after the war. Finally, the bombs shouldn’t have been dropped, not only because it was unnecessary, but because of ethical reasons. Many innocent civilian lives were taken. We had not idea what the long term effects of the radiation from the bombs would do. The Japanese were nearly defeated. Relationships were shaky with the Soviet Union. But is that any reason to drop two destructive weapons on innocent civilians? No. Obviously the bombs played a quicker deciding factor in the surrender of the Japanese. But the war was nearly over anyway and not many more American lives would have been lost.