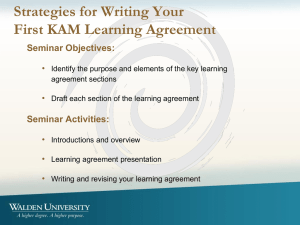

WALDEN UNIVERSITY Core Knowledge Area Module 3: Principles

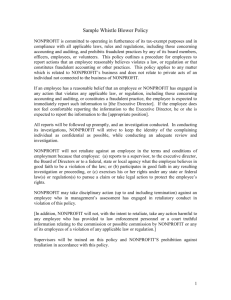

advertisement