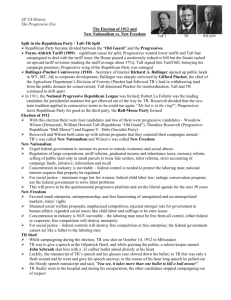

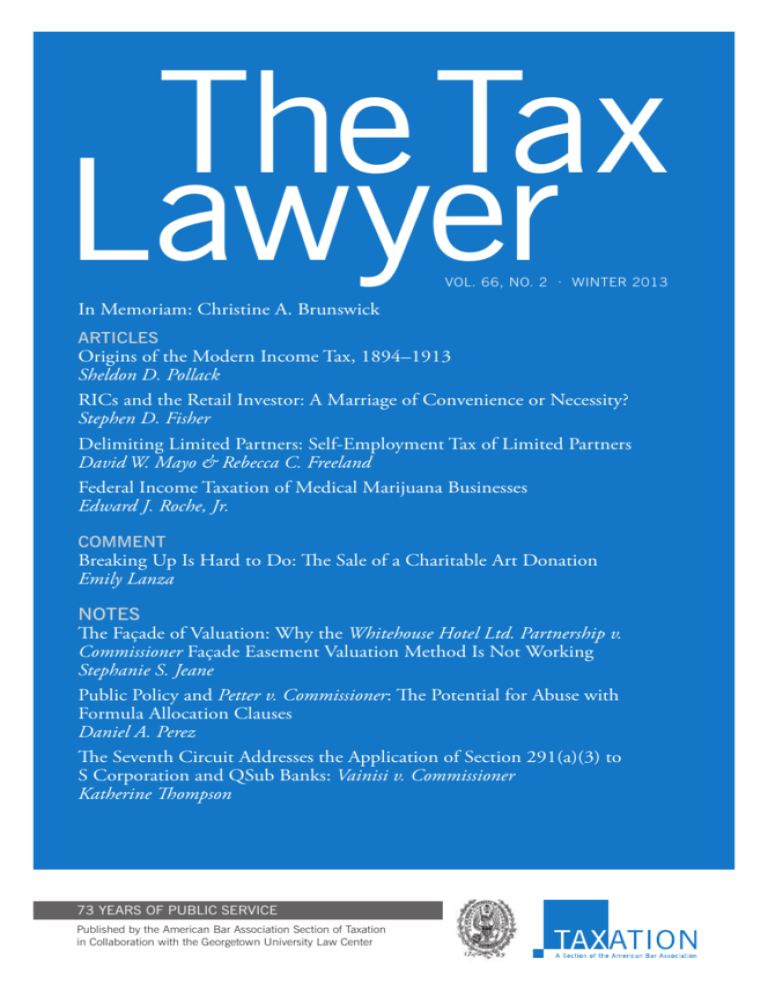

Origins of the Modern Income Tax, 1894–1913

advertisement