DSM-5 and Clinical Diagnosis

advertisement

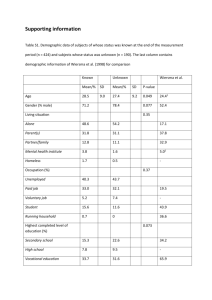

DSM-5 and Clinical Diagnosis: The Major Changes Every Clinician Should Know Thursday June 5, 2014 Jerome C. Wakefield, PhD, DSW, LCSW Professor, School of Social Work and Department of Psychiatry New York University Agenda Welcome and Introduction Disclosure and Caveats Emerging Measures Neurodevelopmental Disorders Depressive Disorders Substance Use Disorders Disclosure and Caveats - I DSM and DSM-5TM are trademarks of the American Psychiatric Association, which is not affiliated with nor endorses anything in this presentation. All DSM-5 diagnostic criteria sets are copyrighted by the American Psychiatric Association, and are cited here only to a degree that falls under fair use in a professional educational setting. I was not officially involved in the development of the DSM-5. Nothing I say here about diagnosis should be taken to apply to any particular individual without a full diagnostic assessment by a qualified professional. Coverage today must be very selective and limited. Many major changes cannot be covered. (NASW -- NYC is offering an all-day workshop Friday June 13 in which I will cover DSM-5 in more detail.) The DSM-5 is mainly about mental disorder diagnosis, but it is important to recognize that the mental health professions have several functions; it is not only about mental disorder. The DSM’s “V Codes” acknowledge this by listing nondisordered conditions for which psychiatrists are commonly consulted, such as normal bereavement, marital or parentchild conflict, and occupational or academic problems. Why do we have a DSM with its categories and detailed diagnostic criteria? Communication Access research Address earlier criticisms of psychiatry The symptom-based criteria addressed many criticisms of the mental health professions Greater reliability and improved communication Symptom-based criteria contained no implicit psychoanalytic assumptions Because the same symptom syndrome could be recognized as a disorder by all schools of thought (i.e., are theory neutral), the new criteria provided a level playing field for competing theories of disorder etiology and cumulative research on treatment Real disorders vs. anti-psychiatry based on definition of disorder Disorders more finely distinguished, better targets for drug development (though it did not work out that way!) Easily applied to epidemiology and screening and general medical practice Response to Rosenhan, US/UK, and other reliability studies; reliability and validity improved DSM-5 Definition of Mental Disorder A mental disorder is a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning. Mental disorders are usually associated with significant distress or disability in social, occupational, or other important activities. An expectable or culturally approved response to a common stressor or loss, such as the death of a loved one, is not a mental disorder. Socially deviant behavior (e.g., political, religious, or sexual) and conflicts that are primarily between the individual and society are not mental disorders unless the deviance or conflict results from a dysfunction in the individual, as described above. Disorder as "Harmful Dysfunction" A dysfunction is: A failure of an internal mechanism to perform one of its natural functions (as ultimately determined by evolutionary design) A disorder if it causes harm, defined by social values to include harm to individual or society Wakefield “The concept of mental disorder.” 1992 American Psychologist The “false positives” problem “Many millions of people with normal grief, gluttony, distractibility, worries, reactions to stress, the temper tantrums of childhood, the forgetting of old age, and 'behavioral addictions' will soon be mislabeled as psychiatrically sick.” (Frances, 2012) The Clinician’s Dilemma Broader categories mean reimbursement to help more people But disorder diagnosis can have negative consequences and may mean medication with side effects An ethical issue we all face within our flawed and selfdefeating system of help DSM-5 Overarching/Structural Changes Arabic numbering of fifth edition – DSM-5 Three sections plus appendices New chapter organization Disorders moved around The elimination of the multiaxial system Terminological changes to NOS and general medical conditions Double ICD-9/ICD-10 coding Cultural interview Dimensionalization where possible DSM Question: When does DSM-5 become “official”? Answer: there is no one answer. When you look at a disorder in DSM-5, it will appear as below. Bot the ICD-9-CM code and the ICD-10-CM code are listed: ICD-10: fuggedaboutit! (for now) ICD-10 was originally scheduled to be adopted in 2013, then delayed until October 1, 2014. On April 1, 2014, Bill H.R. 4302, known as the PAM Act (Protecting Access to Medicare Act), was signed into law by President Obama. As a result of a quietly inserted clause piggybacking on this Bill, implementation of ICD-10-CM was delayed by a further year. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has confirmed that the effective implementation date for ICD-10-CM is now October 1, 2015, a year-and-ahalf away. Until that time, the codes in ICD-10-CM (the U.S. specific adaptation of the WHO’s ICD-10) are not valid for any purpose or use. You may only user ICD-9-CM codes, the ones you have been using from DSM-IV (plus a few modifications for DSM-5). Emerging Measures and Models Emerging Measures and Models Assessment Measures Cultural Formulation Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personnalité Disorders Conditions for Further Study Conditions for further study (or “emerging” categories)-uncoded Attenuated Psychosis Syndrome Depressive Episodes with Short-duration Hypomanic Episodes Persistent Complex Grief Disorder Caffeine Use Disorder Internet Gaming Disorder Neurobehavioral Disorder Associated With Prenatal Alcohol Exposure Suicidal Behavior Disorder Non-suicidal Self-injury Disorder Assessment Measures A dimensional approach depending primarily on an individual’s subjective reports of symptom experiences along with the clinician’s interpretation is consistent with current diagnostic practice. Cross-cutting symptom measures modeled on general medicine’s review of systems can serve as an approach for reviewing critical psychopathological domains. Severity measures are disorder-specific, corresponding closely to the criteria that constitute the disorder definition. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, Version 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) was developed to assess a patient’s ability to perform activities in six areas: understanding and communicating; getting around; self-care; getting along with people; life activities (e.g., household, work/school); and participation in society. Fear Questionnaire – Agoraphobia Subscale Never Occasionall y Half of the Time Most of the Time All of the Time During the past month, I have… 1. felt moments of sudden terror, fear or fright in these situations 0 1 2 3 4 2. felt anxious, worried, or nervous about these situations 0 1 2 3 4 3. had thoughts about panic attacks, uncomfortable physical sensations, getting lost, or being overcome with fear in these situations 0 1 2 3 4 4. felt a racing heart, sweaty, trouble breathing, faint, or shaky in these situations 0 1 2 3 4 5. felt tense muscles, on edge or restless, or trouble relaxing in these situations 0 1 2 3 4 6. avoided, or did not approach or enter, these situations 0 1 2 3 4 7. moved away from these situations, left them early, or remained close to the exits 0 1 2 3 4 8. spent a lot of time preparing for, or procrastinating about (putting off), these situations 0 1 2 3 4 9. distracted myself to avoid thinking about these situations 0 1 2 3 4 10. needed help to cope with these situations (e.g., alcohol or medications, superstitious objects, other people) 0 1 2 3 4 DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 CrossCutting Symptom Measure—Adult DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview The Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI) is a set of fourteen questions that clinicians may use to obtain information during a mental health assessment about the impact of a patient’s culture on key aspects of care. In the CFI, culture refers primarily to the values, orientations, and assumptions that individuals derive from membership in diverse social groups (e.g., ethnic groups, the military, faith communities), which may conform or differ from medical explanations. The term culture also refers to aspects of a person’s background that may affect his or her perspective, such as ethnicity, race, language, or religion. For example People often understand their problems in their own way, which may be similar to or different from how doctors describe the problem. How would you describe your problem? Sometimes people have different ways of describing their problem to their family, friends, or others in their community. How would you describe your problem to them? Why do you think this is happening to you? What do you think are the causes of your [PROBLEM]? PROMPT FURTHER IF REQUIRED: Some people may explain their problem as the result of bad things that happen in their life, problems with others, a physical illness, a spiritual reason, or many other causes. Additional level 2 detailed questions to follow up any answer of interest in main level 1 interview. “Online Enhancements” www.psych.org/dsm5 Inclusion of clinical ratings scales and assessments in print version is limited to those that are most relevant Additional measures used in the field trials are available on-line linked to the various disorders Cultural Formulation Interview also available on-line Terminology change - NOS “Not otherwise specified” (NOS) categories, for disorders that do not fit under specific disorder categories (e.g., “depressive disorder not otherwise specified”), are replaced by a combination of two categories: “other specified” (e.g., “other specified depressive disorder”), in which the clinician provides the reason why the condition does not qualify for specific diagnosis (e.g., subthreshold, or short duration). Options for other specified classifications are provided. “unspecified,” used when no additional explanation is provided as to why the disorder does not meet usual criteria. Elimination of Multiaxial System DSM-IV Multiaxial System Axis I Clinical Disorders, Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention Axis II Personality Disorders, Mental Retardation Axis III General Medical Conditions Axis IV Psychosocial and Environmental Problems Axis V Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Why was the multiaxial system eliminated? To be more consistent with general medicine To be more consistent with the WHO’s ICD It was always stated that the first three axes are the “real” diagnosis, consistent with general medicine. The idea was already illustrated in DSM-IV non-multiaxial recording • Example 1: – 296.23 Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode, Severe Without Psychotic Features – 305.00 Alcohol Abuse – 301.6 Dependent Personality Disorder – Frequent use of denial • Example 2: – 300.4 Dysthymic Disorder – 315.00 Reading Disorder – 382.9 Otitis media, recurrent • Example 3: – V61.1 Partner Relational Problem DSM-IV-TR (ICD-9-CM Coding) AXIS I. Asperger disorder, 299.80 AXIS II. Deferred AXIS III. Generalized non-convulsive epilepsy 345 AXIS IV. Academic/educational problem V 62.3 AXIS V. GAF 51 DSM-5 Single-Axis Coding (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM Codes) 299.00 Autism spectrum disorder; 345 Generalized non-convulsive epilepsy (from chart); V 62.3 Academic/educational problem. How do you record a medical disorder if you are not an MD? One technique: indicate “diagnosis by history” from patient or chart. DSM-IV-TR Multiaxial Coding AXIS I. Dysthymia, 300.4; Noncompliance with treatment V51.81 (NOTE: Listed by V code if a target of treatment; otherwise listed in Axis IV) AXIS II. Borderline Personality Disorder 301.83 AXIS III. Obesity 278 (from history) AXIS IV. Noncompliance with medical treatment. (Listed here if a factor in treatment planning but not a target of treatment] Problems with access to health care: Unavailability of healthcare facilities (V63.9) AXIS V. GAF 43 DSM-5 Single-Axis Coding (ICD-9-CM Codes) 300.4 Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia); 301.83 Borderline personality disorder; 278 Obesity; V15.81 Non-adherence to medical treatment; V63.9 Unavailability of health care facilities. Elimination of the Multiaxial System AXIS 2: Personality disorders and intellectual disability (labeled “mental retardation” in DSM-IV) were on a separate axis 2, but are now listed with all the other disorders, and will simply be listed as an additional or primary diagnosis. Axis 3: General medical disorders will be listed along with the main psychiatric diagnosis. Elimination of Axis IV, Expansion of V Codes Stressors (axis 4) are eliminated, but the V Codes are greatly expanded to all manner of environmental stresses. Also, the V Codes can now be used not only for targets of treatment but also, like the former Axis 4, to specify important contextual factors that influence the target condition’s nature, prognosis, or treatment. Overall, this change seems a plus for contextualizing disorder. No. of V Codes: DSM-IV, 23; DSM-5, 133 Relational problems Problems Related to Family Upbringing Problems Related to Primary Support Group (e.g., disruption by separation) Child abuse and neglect—physical, sexual, psychological Spouse or Partner neglect or abuse, Physical, sexual, psychological Adult neglect or abuse (e.g., abuse by non-spouse/non-partner) Problems of to Access or non-adherence to Medical Care Problems with crime or legal system (e.g., victim of crime, imprisonment) Housing and economic problems (e.g., homelessness, low income, discord with neighbor) Problems with social environment (e.g., acculturation, discrimination) Other psychosocial problems (e.g., religious problems; victim of torture; exposure to disaster; discord with social service provider) Family circumstances (e.g., high expressed emotion; sibling rivalry) Circumstances Personal history (e.g., military service, trauma, lifestyle) Demise of the GAF Axis 5’s Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), now required in many settings, is eliminated as an axis in its own right. Widely used, but criticized as combining functioning and symptoms – e.g., range 41-50: Serious symptoms (e.g., suicidal ideation, severe obsessional rituals, frequent shoplifting) OR any serious impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning (e.g., no friends, unable to keep a job) DSM-5 recommends the WHODAS for assessing adaptive functioning World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) – a comprehensive inventory of social functioning. Focuses exclusively on adaptive functioning and does not depend at all on symptom levels. Used across medical specialties, not specifically tailored for mental health. However, designed for general psychosocial screening, asks questions about longer-term problems such as making new friends, joining in community activities, and living with dignity. May be less suitable than the GAF for focused psychiatric disability evaluations, and clinician time may be a problem. WHODAS Assesses disability across six domains, including understanding and communicating, getting around, self-care, getting along with people, life activities (i.e., household, work, and/or school activities), and participation in society. Question In DSM-5, personality disorders are diagnosed: (a) on a separate axis from other mental disorders (b) without any separate axis, as one form of mental disorder along with all the other categories Neurodevelopmental Disorders Autism spectrum Rates increased from 1/2000 to 1/50 DSM-5 Autism Spectrum narrows definition- not clear how much Autism Spectrum Disorder - II • Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction (ALL) – Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity – Deficits in non-verbal communication – Deficits in developing and maintaining relationships • Restricted repetitive behaviors or interests (2 of 4) – Stereotyped behavior or speech – Need for sameness and routines – Abnormal fixations or restricted interests – Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input Spectrum of severity provided (“ranging from…”) • • Specify current severity for Criterion A and Criterion B: Requiring very substantial support, Requiring substantial support, Requiring support Severity of Social Communication deficits Severity Level Anchor Level 3 Severe deficits; very little initiation of social interactions and minimal response to others: e.g., few words or intelligible speech, makes unusual approaches only to meet needs Level 2 Marked deficits; e.g., speaks simple sentences, interaction limited to narrow special interests Level 1 Without supports in place, deficits cause noticeable impairments; e.g., able to speak in full sentences but conversation fails ASD Controversy The main concern was that changes in diagnostic thresholds at the milder end of the spectrum would eliminate some from diagnosis and lead to loss of services, to which these diagnoses are closely tied. Some studies suggested possible loss of substantial numbers of cases of Asperger’s and also of some autism cases Solution: grandfathering in all previous diagnoses to avoid loss of services (!) “Note: Individuals with a well-established DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified should be given the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.” Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder – changes to ease diagnosis in adults Age of symptom onset requirement raised from age 7 to age 12 Rationale for change: individuals often cannot recall onset before age 7; later “onset” cases the same as earlier age. Criticism: if it’s a developmental disorder, it ought to emerge early Diagnosis in adolescents and adults requires only five symptoms, rather than the six in DSM-IV Examples adjusted to illustrate adult ADHD For example Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g., has difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, or lengthy reading). Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities (e.g., difficulty managing sequential tasks; difficulty keeping materials and belongings in order; messy, disorganized work; has poor time management; fails to meet deadlines). For example continued Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g., schoolwork or homework; for older adolescents and adults, preparing reports, completing forms, reviewing lengthy papers). Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones). Is often forgetful in daily activities (e.g., doing chores, running errands; for older adolescents and adults, returning calls, paying bills, keeping appointments)….. Specific Learning Disorder Replaces and combines all the DSM-IV learning-disorder diagnoses Specifiers indicate specific problem areas (but must be coded separately due to ICD coding) Reflects the fact that these disorders often occur together Specific Learning Disorder • Abandonment of the “discrepancy theory”: DSM-IV required a disparity between level of achievement and IQ to establish a learning disorder vs. poor ability. This requirement is eliminated (only disparity with chronological age and education is now required). • Changing federal regulations now prohibit the diagnosis of learning disorder from requiring a difference between disorder-specific learning and overall IQ. “B. The affected academic skills are substantially and quantifiably below those expected for the individual’s chronological age,…” Specific Learning Disorder • Instead, performance is compared to average expectations for one’s age. • Also, DSM-5 adopts the “response to intervention” (RTI) approach: a trial test of educational interventions is required in order to demonstrate the problem is not easily ameliorable by standard educational techniques, thus that the child requires special services. • Opponents claim that RTI simply identifies low achieving students rather than students with learning disabilities Specific Learning Disorder, Diagnostic Criteria • A. Difficulties learning and using academic skills, as indicated by the presence of at least one of the following symptoms that have persisted for at least 6 months, despite the provision of interventions that target those difficulties…” Questions • In diagnosing ADHD in an adult, by what age must symptoms have appeared? • To what baseline must a child’s performance now be compared in supporting a diagnosis of learning disorder? • Children who were diagnosed with Asperger’s disorder in DSM-IV now appear in DSM-5 under what disorder? Disruptive, Impulse Control, and Conduct Disorders • Oppositional-defiant disorder – Sibling exclusion • Intermittent Explosive Disorder – Addition of verbal aggression • Conduct disorder – Addition of specifier for “with limited prosocial emotions” 60 Depressive Disorders Changes in Organization • Unipolar depressive disorders are now presented in a separate chapter • Major depressive episode criteria are no longer presented separately from major depressive disorder criteria – “This approach will facilitate bedside diagnosis…” (p. xlii) © Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD) 296.99 (F34.8) New Disorder Initially called Temper dysregulation disorder with dysphoria Ridiculed in Slate as “the new temper tantrum disorder” •Al Frances: this disorder "will turn temper tantrums into a mental disorder." DMDD vs Normal Tantrums • Tantrums occur on average at least three times per week • Mood between outbursts is persistently irritable or angry • Present for at least 12 months; no more than a 3 month period w/o symptoms • Present in at least 2 of 3 settings (school, home, with peers) and severe in at least one of these Why was DMDD Added? Main Goal: To address the embarrassment that in just one decade, the diagnosis of child bipolar disorder increased 4000% (40 times as much) Reason: Chronic irritability and tantrums interpreted as childhood manifestations of manic symptoms Children inappropriately treated with mood stabilizers and antipsychotic medication with serious side effects and unknown developmental effects Differential Diagnosis Bipolar disorder includes discrete episodes of mania, not chronic irritability; expansive mood and grandiosity do not occur in DMDD Oppositional defiant disorder does not include chronic mood symptoms prominent in DMDD, less severe Bipolar overrides DMDD, DMDD overrides ODD Axelson Study (2) • “Conclusions—In this clinical sample, DMDD could not be delimited from oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, had limited diagnostic stability, and was not associated with current, future-onset, or parental history of mood or anxiety disorders. These findings raise concerns about the diagnostic utility of DMDD in clinical populations.” (Axelson et al., 2012) DSM-5 Persistent Depressive Disorder Combines Dysthymia and Chronic MDD Research suggests that chronic major and chronic subsyndromal depressions have prognostic factors in common. (However, this research is not very extensive.) Criteria are similar to DSM-IV Dysthymic Disorder except the exclusion of cases with MDE has been removed. Persistent Depressive Disorder Specifiers indicate the relationship between MDE episodes and dysthymic periods during the preceding 2 years: – With pure dysthymic syndrome (no MDE in preceding 2 years) – With persistent major depressive episode (MDE for entire 2 years) – With intermittent major depressive episodes, with current episode (current MDE and at least one two month period below threshold) – With intermittent major depressive episode, without current episode (no current MDE but one or more MDE in preceding two years) Major Depression Bereavement Exclusion Eliminated Just two weeks of general-distress symptoms after loss can qualify for MDD Critics: Danger of over-treatment with meds Reduces dignity of grief Bereavement Exclusion Note In response to criticism, DSM-5 added a “note” reminding the clinician that responses to grief and other significant losses may include feelings of intense sadness and other depressive symptoms that can resemble a depressive episode, and that clinical judgment is required What Does the Evidence Show? Uncomplicated bereavement (and other-stressor) cases do not have elevated recurrence on follow-up Uncomplicated bereavement (and other stressor) cases do not have elevated suicide attempts on follow-up Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) 625.4 (N94.3) Criteria emphasize that symptoms are marked and that mood symptoms are primary – B-criterion: There must be at least one of: marked affective lability (e.g., mood swings; feeling suddenly sad or tearful, or increased sensitivity to rejection), irritability or anger or interpersonal conflicts, depressed mood (e.g., hopelessness, self-deprecating thoughts), or anxiety in the week before the onset of menses, which improves after onset, with sxs minimal or absent in week post-menses – C-criterion: There must be additional depressive symptoms (e.g., lethargy, decreased interest, trouble concentrating, appetite changes, sleep changes, feeling overwhelmed) for a total of at least five B and C symptoms. PMDD (2) – Not merely an exacerbation of pre-existing disorder – Must be present for most cycles in previous year – Confirmed by prospective daily ratings for two cycles Almost all symptoms are depressive symptoms (exception: “Physical symptoms such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, a sensation of “bloating,” or weight gain”) “With Anxious Distress” Specifier Addresses the frequent comorbidity of depression and anxiety (a self-created problem) Important because anxiety indicates more negative MDD outcomes In addition, DSM-5 allows GAD to be diagnosed comorbidly with MDD for the first time. “With Anxious Distress” Specifier • Can specify “With Anxious Distress” if at least two of the following anxiety symptoms during the majority of days: – Feeling keyed up – Restless – Difficulty concentrating – Fear that something awful might happen – Fear of losing control • Can indicate severity (e.g., “with mild anxious distress”) as follows: – Mild: 2 sxs; Moderate: 3 sxs; Moderate-Severe: 4-5 sxs ; Severe: 4-5 sxs with motor agitation Questions • If someone is grieving the loss of a loved one, for how many weeks must they manifest depressive symptoms for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder to be warranted? • but they have enough symptoms to qualify for major depression, are they diagnosed as normally bereaved or as having major depression? Substance Use Disorders • Lumps Abuse and Dependence Adds symptoms to dependence list Reduces diagnostic threshold Critics • Stigmatizes the non-addicted • Different outcome and prognosis Substance Use Disorder DSM-5™ substance use (2 out of 11) • • • • • • • • • • • Larger amounts taken than intended Persistent desire to cut down or control use Great deal of time to obtain, use or recover Craving or strong desire to use Failure to fulfill role obligations Use despite social/interpersonal problems Activities given up or reduced Use where physically hazardous Use despite physical/psychological problem Tolerance Withdrawal DSM-IV dependence/abuse • • • • • • • • • • • Dependence (3) Dependence (4) Dependence (5) Not in DSM-IV Abuse (1) Abuse (4) Dependence (6) Abuse (2) Dependence (7) Dependence (1) Dependence (2) 80 When tolerance and withdrawal don’t count for dependence When taking opioids, sedatives, or stimulants under medical supervision, it is expectable that tolerance and withdrawal will develop. This is NOT evidence of a substance use disorder, which must include compulsive use. “Appropriate” medical supervision precludes shopping for multiple prescriptions. Criteria can still be met when taking the substance under medical supervision if two other symptoms of compulsive use are present. For example, opioid use disorder • 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: – a. A need for markedly increased amounts of opioids to achieve intoxication or desired effect. – b. A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of an opioid. • Note: This criterion is not considered to be met for those taking opioids solely under appropriate medical supervision. • 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: – a. The characteristic opioid withdrawal syndrome (refer to Criteria A and B of the criteria set for opioid withdrawal, pp. 547–548). – b. Opioids (or a closely related substance) are taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms. • Note: This criterion is not considered to be met for those individuals taking opioids solely under appropriate medical supervision. (p. 541) Substance Use Disorder Specifiers Severity specifiers – Mild: 2-3 symptoms – Moderate: 4-5 symptoms – Severe: 6 or more symptoms Polysubstance use disorder eliminated 83 New Withdrawal Categories in DSM-5™ Cannabis withdrawal Caffeine withdrawal • Cessation of prolonged cannabis use followed by 3 or more of • Abrupt cessation of daily use followed by 3 or more of Irritability, anger, or aggression Nervousness or anxious Sleep difficulty Decreased appetite or weight loss – Depressed mood – Restlessness – Physical symptoms (e.g., sweating, fever, chills, headache, etc) – – – – – – – – – Headache Marked fatigue or drowsiness Dysphoric mood or irritability Difficulty concentrating Flu-like symptoms (nausea, vomiting, muscle pain) • Causes clinically significant distress or impairment • Causes clinically significant distress or impairment 84 Questions An individual presenting with 3 out of a possible 11 substance use disorder symptoms would be classified as what level of severity? What new symptom criterion has been added to DSM-5 substance use disorder that did not appear in either DSM-IV abuse or dependence? Thank you for listening If you have further questions about the presentation, you may email them to: wakefield@nyu.edu (responses may be delayed) If you wish to get further in-depth coverage of DSM-5 changes and controversies, NASW-NYC is presenting a workshop by me on Friday, June 13, titled “Mastering DSM-5: Changes, Controversies, and Parts Unknown.” See: https://m360.naswnyc.org/event.aspx?eventID=102534\ Slides are available online: http://www.ctacny.com/dsm-5-and-clinical-diagnosis-the-majorchanges-every-clinician-should-know-about.html