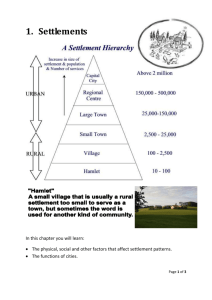

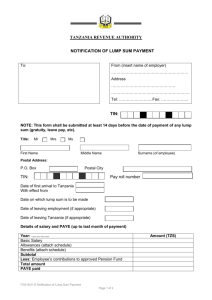

justifying the structured settlement tax subsidy: the use of lump sum

advertisement