working safely with blood

Biology 212: Human Anatomy and Physiology II

***************************************************************************************************

BLOOD

***************************************************************************************************

References: Saladin, KS: Anatomy and Physiology, The Unity of Form and Function (6th ed, 2012)

Be sure you have read and understand Chapter 18 before beginning this lab.

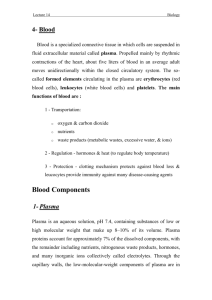

Your body uses blood to carry many different things from one place to another within the body. These include (but are certainly not limited to) different types of cells, water, nutrients, proteins, ions, waste products, hormones, antibodies, oxygen, and carbon dioxide. An average-sized adult has between five and five-and-a-half liters of blood (men have a higher blood volume than women), constantly being pushed through blood vessels by contractions of the heart.

Blood has two basic components: cells and fragments of cells are called formed elements , while the liquid portion of blood consisting of water and all of the solutes dissolved in it is called the plasma . You may also have heard the term serum used to describe blood: serum is what remains of the plasma after the blood has clotted. Both the formed elements and the plasma are constantly being modified to meet the changing needs which the body has for blood, and thus many different blood tests are useful for diagnosing abnormal changes (i.e. diseases) in the body.

WORKING SAFELY WITH BLOOD:

You will be using your own blood in this exercise. It is important that you handle it safely in order to prevent other people from being exposed to it. While it is unlikely that the blood of any student in this class contains infectious agents, to be safe we will treat all blood and everything which has come in contact with that blood as if it does.

1) You do not need to wear gloves if you will come in contact with your own blood, but you must

wear gloves if you come in contact with the blood of any other person or anything contaminated with such blood, no matter how healthy that person may be. Obviously, don’t rub your eyes,

stick your fingers in your mouth, use the bathroom, etc. if your hands are contaminated.

2) Anything which is contaminated with blood must be disinfected before it is disposed of. This

will be done by properly trained personnel in the Biology department. You should place

contaminated material in the containers provided. Your instructor will provide details.

3) Sharp items which are contaminated with blood require special attention to prevent them from

wounding (and thus potentially infecting) another person. All sharp items such as lancets or

breakable glass have a special container for disposal - do not dispose of them with other supplies

4) Wash your hands thoroughly (use soap!) when finished with handling blood.

5 ) If you accidentally spill blood or think you have been exposed to another person’s blood, please

inform your instructor immediately.

PLASMA

We will not be doing any experiments using plasma, but you should understand its composition. Plasma makes up 55% to 60% of the total blood volume. More than 90% of it is water, but plasma contains so many different solutes in so many different concentrations that is has a moderately viscous, or sticky feel. It is normally slightly cloudy and has a light tan or “straw-like” color, although this too can change according to the solutes it contains. You will be able to examine the appearance of plasma when we measure your hematocrit later in this exercise.

Besides being the fluid within which solutes are being carried around the body, the plasma serves three other important functions in the homeostasis of the body:

1) It is one of the largest and most important reservoirs for water within the body. If another organ

or tissue requires more water, it can easily withdraw it from the plasma. If another organ or

tissue has an excess of water, the extra joins the plasma to be carried to the kidneys where it

can be removed.

2) It is one of the most important acid-base buffering systems within the body. It maintains a

relatively stable pH of approximately 7.35 to 7.45 even when acidic and basic molecules are

constantly entering and leaving it. In turn, this helps other fluid compartments of the body,

such as those inside cells (cytoplasm) and outside cells (ground substance) maintain their pH

balances as well.

3) It is very important in maintaining a consistent temperature within the body. When some part

of the body either gains or loses heat (think of breathing cold air, drinking ice water or hot tea,

or being immersed in a cold lake or in a hot-tub) the movement of the body-temperature blood

quickly restores that local temperature to the normal range. Since its own temperature will then

also change slightly, the plasma can signal the autonomic parts of the nervous system that it

needs to increase (e.g. sweating) or decrease (e.g. vasoconstriction of the skin) the rate at

which the body is losing heat, or perhaps even increase the rate of heat production (e.g.

shivering).

Questions for discussion:

If the plasma forms 55 to 60% of your total blood volume, what is the other 40-45% ?

Identify at least ten different solutes carried in the plasma and explain to other members of

your lab group how these get into the blood and their function there.

EXAMINING THE FORMED ELEMENTS OF BLOOD:

The formed elements of the blood consist of six different types of cells and living fragments of another type of cell. We will examine prepared slides of blood which have been stained in such a way to allow you to identify and differentiate among them. All of these slides have been sterilized. so you do not need to wear gloves when examining them.

A word of caution: even the best hematologist can’t accurately identify every single cell in a blood smear.

Many are damaged beyond recognition during p reparation of the slide, or for some other reason don’t show their characteristic appearances, and are jokingly known as “skipocytes” because you should simply skip over them and find another cell. You will drive yourself crazy if you approach this exercise by finding cells and then trying to identify every one of them. Your life, and the life of your lab instructor, will be much easier if instead you figure out the characteristics of one specific type of cell to identify, then scan around the slide until you find some cells which have those characteristics. As you get better at identifying cells, you will find fewer and fewer “skipocytes”.

Exercise 1:

Obtain a microscope and examine slide number 6. This is a “smear”, meaning that the blood was smeared across the slide, allowed to dry, then stained. Thus, you see three-dimensional cells - they were not cut.

As with all slides, bring the image into focus first under the smallest objective lens, then successively work your way up to the highest (400x) magnification. You should observe many round, pale pink or blue cells which do not have nuclei, scattered among which are a small number of cells in which the nucleus is present and stains a moderate to deep blue. Look more carefully, and you should also see what appear to be small, irregular blue structures about 20% the size of the cells. Compare what you see to Figure 5.23 in your Saladin text. Use this figure as well as Figure 18.1, 18.18, and Table 18.6 to help you identify the following formed elements:

Erythrocytes , or red blood cells, are those which do not have a nucleus. These had nuclei when they were developing as erythroblasts , but they exocytosed their nuclei just before they entered the blood. Without nuclei they have no DNA and are incapable of forming new proteins, so they will live for a few months and then die. During their development, however, these cells synthesized large amounts of hemoglobin, so as they circulate they carry a large fraction of both the oxygen and the carbon dioxide which the blood contains.

Notice that erythrocytes are by far the most numerous cells on the slide - greatly outnumbering the other formed elements. Each erythrocyte has a biconcave discoid shape (Figure 18.4) - think of a donut with a thin membrane across the hole. It is approximately 7.5 micrometers in diameter and 2.0 micrometers thick at its rim.

Platelets or thrombocytes , are the small, irregular structures much smaller than the erythrocytes. Your eye may at first think they are merely debris and ignore them, but if you look closely you should see them throughout the slide. They are important in blood clotting (“ hemostasis ”) when a vessel is injured. Be sure you can identify these on the slide.

Questions for discussion:

Approximately how many erythrocytes are contained in each milliliter of blood?

(Caution: your textbook lists the concentration as number per microliter)

Approximately how many platelets are contained in each milliliter of blood?

(Caution: your textbook lists the concentration as number per microliter)

How does this compare to the number of erythrocytes?

Where are erythrocytes produced?

When they get old and damaged, how are erythrocytes removed from the circulating blood?

How does hemoglobin bind oxygen?

Where do the erythrocytes obtain their oxygen? Where do they release it?

Where and how are platelets produced?

What is the role of platelets in blood clotting?

Leukocytes , or white blood cells, make up the remaining formed elements of blood. They are all nucleated. They help the body defend itself against foreign materials and invading organisms, and they clean up dead cells and other debris around the body. All of the leukocytes are ameboid, capable of leaving

(and often reentering) the blood by a process called diapedesis (see page 829 and Figure 21.19 in your

Saladin text). In fact, most of them carry out their normal functions primarily after they have left the blood.

While not entirely accurate, since leukocytes do function within the blood, it would not be wrong to envision the blood and the blood vessels as the highways which leukocytes use to get to other tissues of the body where they are needed.

The leukocytes are classified into two groups according to how granules appear within their cytoplasm when stained with the blue and red dyes commonly used in a laboratory. The granular leukocytes , often shortened to “ granulocytes

”, have visible granules while the agranular leukocytes , often shortened to

“ agranulocytes “ (remember: the prefix “a-“ means “lacking”) do not. The granular leukocytes also have distinctively lobed nuclei, while the agranular leukocytes typically have round or slightly indented nuclei.

Granular Leukocytes (Figures 18.1 and 18.18 in Saladin):

Neutrophils are the most common of the granular leukocytes and, in fact, the most common of all leukocytes (40%-

60%) in the blood. As its name (“neutral-loving”) tells you, its granules stain “neutrally” - neither distinctly blue nor red and they are not as large as the granules of the other two types. The nucleus is quite characteristic, consisting of three or more blue-staining lobes connected by very thin segments.

These cells are phagocytic both within the blood and in other tissues after they leave the blood, and their numbers increase dramatically during almost any type of infection anywhere in the body. You should have no trouble finding many of these on the slide.

Eosinophils are much less commonly seen in the blood, representing only 4% or less of the leukocytes.

The name means “eosin-loving”. Eosin is the stain which provides a red color, and the granules of these cells (actually large lysosomes) are large and a distinctive orange or red color. The nucleus typically consists of two large blue-staining lobes connected by a thin segment, but it is often difficult to see because of all of the large cytoplasmic granules lying on top of it (remember, this is a smear, not a section). These cells are also phagocytes both within the blood and in other tissues, primarily engulfing allergens, small parasites, and the antibody-antigen complexes which result from the normal function of the immune system

(Chapter 21). It may take you a minute or two, but you should be able to identify some of these on the slide.

Basophils , as their name tells you, have granules which “love” the basic dyes which produce a blue color.

These granules are large and stain so darkly that they usually obscure the visibility of the nucleus, which is also blue and shaped like a fat “U” or “S”. These granules are actually vesicles containing the chemicals heparin and histamine which the cell releases during inflammation to dilate small blood vessels, make them leak plasma into surrounding tissues, and decrease its clotting. Unlike the other two types of granular leukocytes, these are not phagocytic. Although common throughout the body, basophils don’t spend much time in the blood so they are rather hard to find, representing a fraction of 1% of all leukocytes in circulating blood. You will not be expected to identify any of these cells in this class, so don’t waste a lot of time trying to find one. However, you should know what they look like in case you happen to run across one.

Agranular Leukocytes (Figures 18.1 and 18.18 in Saladin):

Lymphocytes are relatively common when seen in the blood, 20% to 40% or more of the leukocytes depending on how actively the body is using them to fight infections. You should be able to easily identify these when you see them on the slide. The nucleus is round or slightly indented and stains a uniform dark blue or purple, taking up most of the volume of the cell. The relatively sparse cytoplasm forms a rim around the nucleus and usually stains a medium blue. Since these are “agranular” leukocytes, don’t expect to see any granules in the cytoplasm. While most of the circulating lymphocytes are relatively small, between erythrocytes and other leukocytes in size, they can become very large when fighting an active infection.

There are actually two different typ es of lymphocytes in the blood. Both types are part of the body’s immune system and both are much more active in other tissues after they leave the blood. These two types, however, look exactly the same with routine staining, so you will not be able to t ell them apart. “B”

lymphocytes are responsible for what is called “humoral immunity” - they release large numbers of antibodies into the extracellular matrix of tissues where they are located. “T” lymphocytes produce what is called “cell-mediated immunity” by directly attacking invading or abnormal cells. They are also primarily responsible for rejection of transplanted tissues and for destruction of tumors. Like the basophils, lymphocytes are not phagocytic.

Monocytes are the other type of agranular leukocyte. Relatively large, they typically have a blue or purple nucleus which is slightly indented or even kidney-shaped. There is usually lots of cytoplasm around the nucleus, which stains a lighter blue or blue-gray. These make up 4% to 8% of the leukocytes in the blood, so you should be able to identify them on the slide. These are the most active phagocytes of all of the leukocytes. When they leave the blood, they form the macrophages which we have been discussing in different tissues and organs throughout this class.

Questions for discussion:

Approximately how many leukocytes (all types) are contained in each milliliter of blood?

(Caution: your textbook lists the concentration as number per microliter)

How does this compare to the number of erythrocytes? To the number of platelets?

Where and how are leukocytes produced?

What is the function of each type of leukocyte?

Exercise 2:

Draw from memory a typical erythrocyte, monocyte, lymphocyte, basophil, eosinophil, neutrophil, and platelet. Pay attention to the size of each one, the shape and color of its nucleus (if present), and the number, size and color of its granules (if present).

NOTE: The purpose of this is NOT to produce a pretty or a detailed picture. It is to be sure you understand what each of the formed elements should look like. You will just be wasting your time if you look at your book while you do this: DO IT FROM MEMORY, using the book as a reference when necessary. Discuss your drawing with other members of your lab group and make any necessary corrections.

Exercise 3:

Working from memory, discuss again and compare the functions of each type of formed element listed above. Don’t move on until every person in your lab group can do this!

DIFFERENTIAL WHITE BLOOD CELL COUNT:

Determining the proportions of each type of leukocyte in the blood is a common and useful tool in detecting and diagnosing diseases. The numbers of each type can dramatically and quickly change in response to such things as infections, inflammations, allergies, or diseases of specific organs so it often provides one of the first indications that something is wrong.

Exercise 4:

Use the prepared slide of blood (#6) to do a differential white blood cell count. Start at one edge of the smear and move the slide in a systematic manner as you count - either up and down or side to side - to avoid skipping large areas or repeating any areas. Ignore all of the erythrocytes and platelets that you see - you are only interested in leukocytes (white blood cells). Keep a record in the space below of each type of leukocyte you identify until you have counted and recorded exactly 100 cells. This gives you the percentage of each type. For example, if you observed 41 neutrophils when counting 100 cells, then neutrophils form approximately 41% of leukocytes on the slide.

Number of Neutrophils: _____

Number of Eosinophils: _____

Number of Basophils: _____

Number of Lymphocytes: _____

Number of Monocytes: _____

Questions for discussion:

How do the results of this count compare to the expected percentages of each type of cell?

What information might it give your doctor if the percentage of neutrophils in your blood was significantly increased?

Of eosiniphils?

Of lymphocytes?

Of monocytes?

Of basophils?

GETTING SAMPLES OF YOUR BLOOD:

For the last two parts of this lab exercise, measuring your hematocrit and determining your blood type, you need to obtain samples of your blood from a finger. Be sure you have read and understand the information about “Working Safely With Blood” at the beginning of this exercise.

In order to minimize the number of times you will need to cause your finger to bleed (ideally, just once), be sure you have read through both “Hematocrit” and “Blood Typing” sections below and know what samples you need to obtain before you begin, or you may have to stick yourself again.

Exercise 5:

1) Obtain a packaged alcohol wipe and a couple of pieces of paper towel.

2) Obtain two capillary tubes marked with a thin red band at one end. These will draw blood into

them by capillary action, and they contain heparin to prevent that blood from clotting. You will also need a small tray of clay (“Critoseal”), used for sealing off one end of each capillary tube

after it contains blood, and three or four clean toothpicks.

3) Obtain two glass slides. Label one slide “Rh”.

Use a wax pencil to divide the other slide in half. Label one side “A” and the other side “B”.

4) Obtain small bottles of “Anti-A Serum”, “Anti-B Serum”, and “Anti-Rh Serum”. Place one drop of “Anti-A Serum” on the slide labelled “A”, a drop of “Anti-B Serum” on the slide labelled “B”, and a drop of “Anti-Rh Serum” on the slide labelled “Rh”,

5) Obtain an “Autolet” device for lancing your finger. Notice that this is spring-loaded and holds

a sharp lancet protected by a plastic tip. Push the tip into the Autolet and twist the plastic tip

to remove it and expose the lancet.

6) Keeping your hand low, use the alcohol swab to scrub the side of either your middle or fourth

(ring) finger about halfway down its distal segment. Let the alcohol air-dry for a few seconds.

7) Use the Autolet to lance your finger. A drop of blood should immediately appear - wipe it away

with a paper towel. A second drop of blood should flow onto your skin. If not, you may squeeze the finger gently, but if this doesn’t work you will probably have to repeat the lancing.

8) Still holding your finger low, place the tip of a capillary tube into the drop of blood, holding the

tube so that it points slightly downward away from the finger. Blood will be drawn into the

tube, and it is OK if small amounts of air are also drawn in. When the tube is half to two-thirds

full (no more), set it flat on your lab table and fill the second capillary tube. Set it flat also.

If you are having trouble getting blood, you can skip filling the second tube.

9) Wipe the blood off of your finger with a paper towel and get another drop to appear on the

skin. Touch this drop to one of the drops of antiserum you previously put on a slide, wipe off

your finger, and repeat this process with the other two drops of antiserum. Immediately use

clean toothpicks to mix each blood sample with its antiserum.

10) Keeping it flat, pick up one of the capillary tubes. Firmly hold a finger against one end

and plug the other end by pressing it into the clay, twisting gently, and removing it. Repeat

with the other tube. You may leave them in the clay for a few minutes until you are ready to

measure your hematocrit, but be careful not to accidently break them.

11) You are done bleeding. Apply pressure to the puncture site for a minute or two with a piece

of paper towel - the bleeding should stop. Now would be a good time to properly dispose of contaminated supplies, but don’t waste too much time.

BLOOD TYPING:

Blood transfusions from one person to another were first attempted in the 1700's, and the results were not always good. Some patients accepted the new blood with few problems, but others experienced severe reactions leading to death. There was clearly something in blood which was causing these problems. We now know that these reactions were a normal part of the body’s immune system.

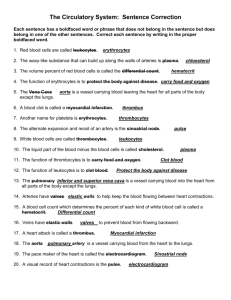

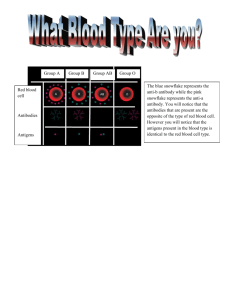

All cells, including those of the blood, carry molecules (usually glycoproteins) called antigens on their surfaces. During fetal development, the body learns which antigens are normally present on its cells and learns to ignore them - this is called “tolerance”. When exposed to any other antigens, however, the immune system responds by producing proteins called antibodies which will attack the abnormal antibodies, destroying them and the cells to which they are attached. Thus, a person does not normally react against their own cells, but will destroy those that come from another person by producing antibodies against them.

In blood typing and blood transfusions, the antigens of importance are found on the erythrocytes, or red blood cells. The immune system causes erythrocytes which carry the wrong antigens to first clump together (“ agglutinate ”) and then be destroyed (see Figures 18.14 and 18.15 in your Saladin text).

Unfortunately, this agglutination can block the blood vessels throughout the body and kill the patients before the abnormal cells can be destroyed.

More than 100 different antigens have been identified on the surfaces of erythrocytes. Most of these cause either no symptoms or only relative moderate reactions (fever, joint pain, nausea) if they are transfused into the wrong person, but three of them can cause the serious reactions which can lead to permanent disability and death. These are called the “A”, “B”, and “Rh” antigens. Blood is classified into specific groups or “types” depending on which of these antigens are present or absent on the erythrocytes.

The “A” and “B” antigens are considered together as the “ABO” group, while the Rh antigen is considered its own group.

We will use this property of agglutination to determine which of the antigens you do or do not have on your erythrocytes - that is, what “blood type” you have. Remember: your immune system must do two things: it must form antibodies against all of the antigens which are not normally found on your cells, while at the same time NOT forming antibodies against any antigens which your cells DO have. In Exercise 5 above you mixed a sample of your blood with serum taken from patients who had formed antibodies against each antigen (the “antiserum” you put on the slides). This will allow you to identify the antigens which your erythrocytes carry.

Exercise 6:

You should complete this exercise within only five or ten minutes of the time you mixed a sample of your blood with each antiserum. Otherwise, the slides will dry out and be useless to you.

Examine those slides, gently rocking each one back and forth to make the fluid gently flow back and forth. Determine if the erythrocytes remain evenly suspended or if they have clumped together (Figure

18.14 in Saladin). If they clumped when mixed with the antiserum for one of the three antigens we are testing, that indicates that you have this specific antigen on your erythrocytes. If they do not clump, you do not have that antigen. Your plasma, in turn, will contain antibodies against any of the antigens not normally found on your cells, but will not contain any antibodies against your own antigens.

There are, of course, many different combinations. Your erythrocytes may have clumped with just one antiserum, two of the antisera, all three of the antisera, or none of the antisera. Based on your results, referring to the chart below:

What is your blood type for both the ABO group?

What is your blood type for the Rh group?

Which antibodies would be present in your plasma?

ABO Blood

Type

A

Antigen Present on Your

Erythrocytes

A

Antibodies Present in Your Plasma

Anti-B

% of US Asian

Population

36

% of US Black

Population

28

% of US White

Population

39

B

AB

O

B

A and

B

Anti-A

None

Neither A nor B Anti-A and Anti-B

22

8

34

20

5

47

11

4

46

Rh Blood

Type

Antigen Present on Your

Erythrocytes

Positive Rh

Negative None

Antibodies Present in Your Plasma

None

Anti-Rh

% of US Asian

Population

% of US Black

Population

% of US White

Population

99

1

91

9

85

15

HEMATOCRIT:

The hematocrit, or packed cell volume, is another common laboratory test to help determine the state of your health. It is relatively simple to do. The small tube of of blood you just obtained is centrifuged for a few minutes to pack the formed elements at the bottom and leave the plasma at the top, after which the percentage of each can be easily measured. Since erythrocytes are a very large majority of formed elements in blood and are all approximately the same size, the hematocrit quickly and accurately indicates if you do not have enough of them.

Exercise 7:

This exercise should be done within half an hour of filling the capillary tube. Place it into the centrifuge designed for this, being sure it fits firmly into a slot. The clay-plugged end must point outward and touch the rubber rim. Remember the number of the slot containing your tube - they all look alike.

When enough tubes are loaded, your lab instructor will properly close the centrifuge and turn it on for four or five minutes.

When the centrifuge has stopped, remove your tube and examine it. Observe that there are three separate layers (Figure 18.2 in Saladin). The bottom of the tube now contains the erythrocytes packed tightly together, the top of the tube contains the straw-colored plasma, and there is a very thin layer of leukocytes and platelets between these two.

Use the microhematocrit reader (your lab instructor will show you how) to determine the percentages of eythrocytes, leukocytes + platelets, and plasma in your blood sample. If this reader is not available, you can easily calculate these percentages using a millimeter ruler to measure the height of each of the three layers in the tube as well as the overall height of the total blood sample (all three layers). Use the formula

Percentage of element in blood = Height of layer you are measuring (mm) X 100

Overall height of total sample (mm)

Record your data here:

% Eythrocytes ________ % Leukocytes+Platelets _________ % Plasma ________

Questions for discussion:

How do your results compare to normal or expected values?

How do your results compare to those of other members of your lab group?

How do normal hematocrit values differ between men and women?

Why do you think such a difference might exist?

Define the term “anemia”. Describe its causes and explain its dangers.

If your hematocrit were abnormally low, what might you do to increase it?

If your hematocrit were abnormally high, what might you do to decrease it?

Exercise 8: Cleanup:

Before you leave, be sure that you have properly disposed of all blood-contaminated materials. Specifically: Autolet/lancets and capillary tubes should be placed in the

“sharps” container. Glass slides should be in the proper container. Paper towels and any other paper items should be in the appropriate container. Put the clay trays on the table at the front of the room - your instructor will decontaminate these with bleach.

Be sure to wash your hands thoroughly.