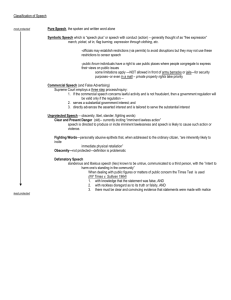

The Semantics of Racial Epithets

advertisement