NIKE – THE ‘GODDESS OF MARKETING’

Do

No

tC

op

y

MKTG - 088

This case was written by Shirisha Regani, under the direction of Sanjib Dutta, ICFAI Center for Management

Research (ICMR). It is intended to be used as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or

ineffective handling of a management situation.

The case was compiled from published sources.

2003, ICFAI Center for Management Research. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic or mechanical, without

permission.

To order copies, call 0091-40-2343-0462/63/64 or write to ICFAI Center for Management Research, Plot # 49, Nagarjuna

Hills, Hyderabad 500 082, India or email icmr@icfai.org. Website: www.icmrindia.or

MKTG/088

NIKE – THE ‘GODDESS OF MARKETING’

“For years, we thought of ourselves as a production-oriented company, meaning we put all our

emphasis on designing and manufacturing the product. But now we understand that the most

important thing we do is market the product. We’ve come around to saying that Nike is a

marketing oriented company and the product is our most important marketing tool.”

y

-Phil Knight, CEO of Nike in the late 1980s1.

op

“Nike is a manufacturer, but really it’s just a marketing company.”

-John Shanley, Securities analyst at Wells Fargo's Shanley in 20032.

tC

ADVERTISER OF THE YEAR

No

In June 2003, Phil Knight (Knight), the founder and CEO of Nike Inc., (Nike), received the

“Advertiser of the Year” award, at the 50th Cannes International Advertising Festival, one of the

major annual advertising events in the world. It was a historical moment because Knight was the

first person to win the award twice (He had received the award in 1994 also). Speaking on the

occasion, Knight said, “It’s the most prestigious award in the world advertising industry and I feel

pretty good about it. Especially, winning it for the second time. It is a huge honor for the

company.”3

Do

Analysts said that Nike had come a long way since it began operations in the 1960s. In the early

years of the business, Knight did not believe in advertising or marketing. He preferred instead, to

rely on word-of-mouth publicity among athletes. This served Nike well enough for some years.

However, in the late-1980s, Nike was overtaken in sales by competitor Reebok4, which introduced

training shoes designed specially for women (who had become more fitness conscious by that

time). In a bid to recapture market share, Nike introduced several new models of shoes designed

for different sports. In addition to introducing new shoes, Knight also realized the importance of

marketing and began to set aside a significant part of corporate revenues for advertising and

marketing.

1

2

wwwfl.ebs.de

Larry Barrett and Sean Gallagher, New Balance: Shoe Fits, Baseline, November 1, 2003.

3

Stefano Hatfield, What makes Nike’s advertising tick, The Guardian, June 17, 2003.

4

A major manufacturer of athletic shoes in the US, Reebok was started by Paul Fireman in the late 1970s.

Reebok was a major competitor of Nike.

This case was written by Shirisha Regani, under the direction of Sanjib Dutta, ICFAI Center for Management

Research (ICMR).

2003, ICFAI Center for Management Research. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic or mechanical, without

permission.

To order copies, call 0091-40-2343-0462/63/64 or write to ICFAI Center for Management Research, Plot # 49, Nagarjuna

Hills, Hyderabad 500 082, India or email icmr@icfai.org. Website: www.icmrindia.or

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

By the 1990s, Nike was one of the best advertisers in the world, Nike was well known for its

unique soulful advertisements (ads), which, analysts said, appealed to viewers’ emotions rather

than their rationality. Most of the ads featured celebrities from different sporting areas. The

company was also attuned to the tastes and sensibilities of the public and tried to create ads that

would appeal to the maximum number of people. In 2003, Nike was the market leader in sports

goods and one of the most popular brands in the world. The company’s logo, the ‘swoosh’ was

thought to be one of the best logos ever designed and had a high degree of recall value. Analysts

said that the recognition of the ‘swoosh’ rivaled the recognition levels of the Stars and Stripes of

the American Flag or the Golden Arches logo of McDonalds5.

BACKGROUND

op

y

The future co-founders of Nike met in 1957, when Knight was an undergraduate student and

middle-distance athlete at the University of Oregon (which was known for having the best track

program in the country) and Bill Bowerman (Bowerman), the athletics coach. In the early 1960s,

when Knight was doing his MBA at Stanford University, he submitted his marketing research

dissertation on the US shoe manufacturing industry. His assertion was that low cost, high quality

running shoes could be imported from labor-rich Asian countries like Japan and sold in the US to

end Germany’s domination in the industry.

No

tC

In 1962, while on a world tour, Knight met the management of the Onitsuka Company (Onitsuka)

of Japan, which manufactured high quality athletic shoes under the brand name ‘Tiger’. He

arranged for these shoes to be imported to the US for sale under the name ‘Blue Ribbon Shoes’

(BRS) (A name he thought up when the management of Onitsuka asked him about which company

he represented. BRS became the forerunner of Nike). In late 1963, Knight received his first

shipment of 200 Tiger shoes. In 1964, Knight and Bowerman formed a partnership, with each of

them contributing $500 and BRS formally came into being. Knight did not have the money to do

any formal advertising for his products. Instead, he crafted his ‘grassroots’ philosophy of selling

shoes. He believed in going out to the athletes who constituted his main market, to sell his shoes.

The first shoes were sold from the basement of Knight’s house and the backs of trucks and cars at

local track events. The athletes who wore the shoes were asked for feedback to improve future

shoe designs. By the end of 1964, BRS had sold 1300 pairs of shoes with $8000 in revenues.

Do

In 1965, the partners hired Jeff Johnson (Johnson), the first full time employee of BRS. Johnson

was formerly a salesperson for Adidas shoes6. In 1966, Johnson helped open the first exclusive

BRS store in California. Sales of the shoes grew and in 1969, Knight resigned from his job at the

Portland University and devoted himself to BRS full time. By the end of the 1960s, BRS had 20

full time employees and several retail stores.

By 1971, BRS started manufacturing its own line of athletic shoes in addition to selling Tiger

shoes. For the new line of shoes, Johnson thought up the name Nike7. Carolyn Davidson, an

acquaintance of Knight, designed the ‘Swoosh’ symbol, which was a graphic representation of the

wing of Goddess Nike. (Refer Exhibit-I) In return for what became one of the most recognized

symbols in advertising, Knight paid her $35.

5

A very popular restaurant chain based in the US and operating in most of the countries around the world.

6

Adidas (founded in 1948 by Adi Dassler) was a German manufacturer of athletic shoes, apparel and

sporting goods. In 2003, Adidas was the number two manufacturer of sporting goods behind Nike.

7

Nike (pronounced NI-KEY) was the winged goddess of victory according to Greek mythology. She sat at

the side of Zeus, the ruler of the Olympic pantheon, in Olympus. A mystical presence, symbolizing

victorious encounters, Nike presided over history’s earliest battlefields.

3

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

In the early 1970s, Nike roped in its first celebrity endorser. Steve Prefontaine (Prefontaine), an

American middle distance runner was the first sports celebrity to wear Nike shoes. Prefontaine was

also coached by Bowerman and played an important role in the design of Nike shoes in the early

years. Impressed by the design of Nike shoes, Prefontaine began wearing these shoes at all track

meets and also converted a number of his fellow athletes to wearing Nike shoes. Nike also began

the practice of sponsoring school teams by giving them shoes and clothes with the Nike name and

logo, to increase the visibility of the brand.

The first shoe with the Swoosh logo came out in early 1972. In 1972, following distribution

differences, BRS parted ways with Onitsuka and from then BRS only sold shoes manufactured

under the Nike brand. T-shirts, with the Nike name and logo printed across them were introduced

at the pre-Olympic trials in 1972, marking the beginning of the company’s apparel business.

During the first half of the 1970s, sales of Nike shoes grew from $10 million to $270 million. The

growth was facilitated by the creation of revolutionary shoe designs like the waffle sole and the air

cushioned sole system, known as ‘Nike Air’.

op

y

In the 1970s, BRS developed a marketing strategy based on the ‘pyramid of influence’, which the

company believed, characterized the athletic footwear market. The pyramid theory suggested that,

if a company concentrated its marketing efforts at the people who were at the top of the customer

pyramid, the effects would trickle down to the lower levels, resulting in an increase in the sales of

the company (This concept has been explained elsewhere in the case).

tC

In 1978, BRS officially changed its name to Nike Inc., in keeping with the popularity of its brand.

Nike rapidly expanded its product line during the 1970s and early 1980s and introduced a wide

variety of shoes for different sports. Models such as Nike-Air and Air Force I for basketball and

the Nike-Air and Air Ace shoes for tennis were introduced over the years (By the early 1980s, the

company had over 200 shoe models in its product line).

No

In 1980, Nike went for a public issue of two million shares of common stock. It also opened a

Sports Research and Development Lab in Exeter, New Hampshire, US. In 1981, Nike International

Ltd. was formed to serve a growing overseas market. At the 1984 Olympics, 58 Nike-sponsored

athletes, from around the world, won a total of 65 medals. This brought the company immense

publicity.

Do

In 1985, the company signed a contract with Michael Jordan (Jordan), an NBA8 player for the

Chicago Bulls9, who went on to become one of the most successful celebrities ever to endorse

Nike. Nike introduced a range of shoes called ‘Air Jordan’, named after the player. In 1986, the

revenues of the company crossed the one billion dollars mark for the first time. In 1987, Nike

introduced the first cross-training shoe, which could be used for running as well as indoor sports.

In 1988, Nike adopted a new punch-line which said “Just Do It”. The punch line was credited to

Dan Wieden, a partner of Wieden & Kennedy, a Portland-based ad agency, which was Nike’s

advertising partner. A series of advertising campaigns highlighting the new punch-line were also

initiated.

By 1991, Nike had become the world’s first sports and fitness-equipment company to surpass $3

billion in total revenues. The year 1992 saw the opening of the first Niketown in Chicago.

Niketown was a specialized store, which showcased the different products developed by Nike over

8

NBA is the National Basketball Association of the US. The NBA was first formed in 1949 and, as of early2003, comprised of 30 teams.

9

The Chicago Bulls were a major NBA basketball team. The team joined the NBA in the 1966-67 basketball

season.

4

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

the years. Nike Asia was formed in 1997. In 1998, the company signed a $17 million annual

endorsement deal with the Brazilian football team. In 2000, Nike signed a £30010 million deal with

Manchester United, a premier league football club based in Manchester, England, that gave the

company rights to all of the club’s merchandise. By the end of 2002, Nike’s products were sold in

over 140 countries around the world. In the fiscal year ended May 2003, Nike’s revenues exceeded

$10 billion (Refer Exhibit-II for Income Statement).

ELEMENTS OF NIKE’S MARKETING STRATEGY

Since the 1980s, marketing has played a very important role in Nike’s corporate strategy. Knight

realized that savvy advertising would go a long way in helping the brand reach out to the target

market and also create a unique positioning for Nike. The company spent about 10 per cent of its

global revenues every year on demand creation. Out of this, a major part was allotted to celebrity

endorsements and the rest, to communications. Some elements of Nike’s marketing strategy are

outlined below:

y

Personal Marketing

No

tC

op

Personal marketing played an important role in Nike’s marketing efforts right from the early years.

In the initial stages, when the company did not have money for advertisements, the shoes were

promoted by distributing or selling them at local track events. The company also followed the

policy of employing people who were athletically oriented as it believed that they would be able to

communicate better with athletes, who constituted the primary target market. For a decade, starting

in the mid-1960s, the company's revenues grew at nearly triple-digit rates. “They managed to

create a need where none had existed,” said Jennifer Black Groves, executive vice president of

Black & Co, a Portland-based investment firm.11 Nike was able to increase the popularity of its

products by pushing shoes at athletes, who would otherwise not have known about them, because

of lack of advertisement.

Do

Personal marketing was used even after Nike grew to become the most successful sports goods

company in the world. The company adopted a unique method of grassroots marketing by

employing people called EKINs (Nike spelt backwards), whose job was to hit the roads and bring

Nike closer to the general public. The primary job function of EKINs was to spread the “Nike

gospel” among the public by visiting stores to introduce product innovations or explain the

functions of different product features to the managers or the people visiting the stores. They also

checked store displays and layouts and interacted with the public to find the pulse of the market.

EKINs were an important source of information and feedback for the people back at the Nike

offices.

Marketing Pyramid

Nike believed in the theory of the marketing pyramid. The pyramid consisted of three levels – at

the top were serious athletes who devoted themselves to sport, at the second level were weekend

athletes who were involved with sport as a leisure activity and at the lowest level were the millions

of Americans who wore sports shoes in a casual way, without using them for any sport. Nike

targeted the top level of the pyramid by retailing through specialty stores. The second level was

also catered to through sporting goods stores. However, in order to maintain its high-quality brand

name, Nike tended to avoid the lower end group and the retail systems they preferred (primarily

departmental stores).

10

£ 1= $ 1.76 as in December 2003.

11

Kenneth Labich, Nike vs. Reebok, Fortune, September 18, 1995.

5

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

The idea behind the pyramid strategy was to ensure that Nike shoes were worn by the most

popular and visible athletes at the top of the pyramid. Their influence would automatically trickle

down to the lower level customers who would want to emulate the stars, thus increasing Nike’s

appeal. Nike, therefore, concentrated its marketing activities on the top level players. “It was clear

to me that to see famous athletes wearing Nike shoes was more convincing than anything we could

say about them,” said Knight.12

Knight also believed that if the “five cool guys”, i.e. the best and most popular athletes in a

reference group (which could be a sports team, college or school) wore Nike shoes, all the others

would want to emulate them and wear the shoes too. This strategy worked quite effectively and by

the late 1990s, Nike was the market leader in athletic shoes.

op

y

By using the pyramid and reference group strategies, Nike traded on people’s tendency to emulate

more successful people. For instance, Nike realized that many basketball fans would want to be

like Jordan. Nike understood their wish and used it to sell its products. The company reasoned that

if people wanted to be as good as Jordan athletically, they would also want to look like him and

wear the shoes that he played in. They would believe that if he was able to play so well in those

shoes, they would probably play like him by wearing the same shoes.

Celebrity Endorsements

tC

Celebrity Endorsements had always been an important part of Nike’s marketing strategy. The

importance of celebrity endorsements to the company was underlined by the fact that Knight

described them as one part of the “three legged stool” which lay behind Nike's phenomenal growth

since the early 1980s, the other two being product design and advertisements.13 Nike felt that

athletes had an affinity to sports products and hence were better endorsers of those products.

No

Prefontaine was the first celebrity to endorse Nike. Analysts felt that Prefontaine set the spirit for

future endorsers of Nike who, like Prefontaine, were committed to sport and were often rebellious

by nature, entering into battle with superiors in the interest of sport.

Do

Jordan was the most famous celebrity to endorse Nike. After signing on Jordan, the company

created special shoes based on Jordan called ‘Air Jordan’. In 1997, Nike also created a separate

manufacturing unit to manufacture Air Jordan shoes, which were the best selling Nike shoes, till

the early 2000s, years after Jordan had retired from the sport. (In Jordan’s first season under the

Nike logo, Air Jordan shoes brought in $153 million in revenue). The black, red and white Nike

shoes worn by Jordan were banned by the NBA for being too colorful for the sport. It was rumored

that Jordan was fined $1000 every time he wore the shoes to a game, but Jordan defied the NBA

by wearing the shoes for every game. Analysts said that this further increased the appeal of the

brand as one favored by those who did not bow to the rules.

In the late 1990s, Nike made its foray into golf equipment. To mark this event, the company signed

a five year long contract with Tiger Woods (Woods) in 2000, to endorse Nike products. Nike paid

Woods $100 million for the five-year deal. Several people felt that the company was overspending,

until Woods won his second Masters Golf title in 2001.

In 2003, Nike signed on LeBron James (James), a high school basketball player, in a $90 million

deal for seven years. This move was severely criticized due to the fact that James had, till then,

never played professionally and had participated in only high school basketball games. Analysts

12

wwwfl.ebs.de

13

Stefano Hatfield, What makes Nike’s advertising tick, The Guardian, June 17, 2003.

6

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

speculated that the move to sign him on was prompted by the fact that Nike’s rivals Adidas and

Reebok were also vying for James, and Nike wanted to beat them to it. They also felt that Nike

was probably looking at James as a replacement for Jordan, after whose retirement in 1999, Nike

did not have a basketball celebrity.

However, analysts felt that it was a little far-fetched to pay someone so inexperienced, such a huge

amount. “The Tiger (Woods) deal was arguably more important because Nike was entering the

golf market and they had to establish an identity. The addition of LeBron isn’t necessarily as

instrumental in the basketball market as Tiger was for golf, so a big part of hiring LeBron is

preventing Reebok and Adidas from getting him,” said Jamelah Leddy, an analyst for McAdams

Wright Ragen, a broker-trader offering investor research in Seattle.14 However, some others felt

that signing on James would appeal to teenage boys, who constituted the main market for

basketball shoes (Refer Exhibit-III for the market shares of the three major players in basketball

shoes).

tC

op

y

Analysts said that dedication to sport and excellence was the commonality among all the

celebrities who endorsed Nike. All Nike endorsers like Jordan, Woods, Andre Agassi (tennis),

Ronaldo (soccer), etc., had been at the top of their sports at one time or another. Analysts also said

that all of them also had one thing in common – attitude. Prefontaine used to say, “When people

ask me why I run, I tell them a lot of people run races to see who’s fastest. I run races to see who

has the most guts.” Analysts said that all the later day endorsers were also characterized by the

same attitude.15

Advertisement

No

From signing individual athletes, the company moved on to signing deals with college teams, the

Dallas Cowboys16 and Brazil’s national soccer squad in the late 1990s. In the early-2000s, the

company considered sponsoring special events, like soccer matches and golf tournaments to

increase brand publicity. “We promote our athletes and the brand while at the same time making

money on the event. It’s a pretty nice synergy,” said Knight.17 Using professional athletes in their

advertisement campaigns was both efficient and effective for Nike because celebrities acted as a

reference point and created immediate appeal.

Do

Nike was well known for its spontaneous and soulful ads. Analysts said that the ads brought the

brand closer to people and made it a part of their lives. Using celebrities in the ads also gave the

brand instant recognition and appeal and helped it reach out to people easily. Commenting on the

ads featuring celebrities, Knight said, “It saves us a lot of time. Sports are at the heart of American

culture, so a lot of emotion already exists around it. Emotions are always hard to explain, but

there’s something inspirational about watching athletes push the limits of performance. You can’t

explain much in 60 seconds, but when you show Michael Jordan, you don’t have to.”18

Analysts also said that another reason why Nike ads were so spontaneous and successful was that

the company did not pre-test them on a target market, like many other companies did. They said

that pre-testing often resulted in the loss of important themes and ideas in the ads and made the ads

14

William McCall, “Nike Outbids Reebok for LeBron James”, The Guardian, May 22, 2003.

15

www.nike.com

16

An American football team.

17

Ronald B. Lieber, Just Redo It, Fortune, June 23, 1997.

18

www.lehigh.edu

7

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

very stiff. “Nike never pre-tested any of its campaigns and we took the responsibility of what we

were creating rather than passing the buck,”19 said Dan Wieden (Wieden), a partner in Wieden &

Kennedy, Nike’s ad agency. Wieden also said that companies learnt more by doing rather than

testing.

Though many of Nike’s ads featured celebrities, some of the most successful ones were those that

featured ordinary people. Research conducted by Nike in the 1990s showed that people did not

always want to be like someone else. Often, they just wanted to be themselves. With this idea in

mind, Nike made ads around individual athleticism and success. The ads showed ordinary people

enjoying sports as part of their daily life. Therefore, the ads had the ability to relate to the everyday

lives of people. They also implied that everybody had the ability to become famous and achieve

great things (Nike won its first award at Cannes for one of these ads).

y

Nike continued with the trend of supporting the individual and athleticism as opposed to revolving

its entire campaign around professional athletes, to better reflect the changing view of society.

Nike’s marketing campaigns reflected the popular preferences in society and the stress that society

put on individual uniqueness.

No

Customization

tC

op

Stuart Elliot, an advertisement columnist with The New York Times, recollected the time when ad

campaigns like “Instant Karma” and “Revolution” hit the industry. “There was something utterly

new about the attitude and the tone,” he said. “The way in which they targeted the serious athlete,

the confident, jocular attitude, the tongue-in-cheek style that’s smart, sassy and smart-alecky - but

not too smart-alecky. The use of black athletes at a time when the industry was shying away from

them and then this whole low-key way they had of under-selling everything.”20 Analysts felt that

Nike ads were an ideal mix of entertainment and information and played an important role in

taking the company to its position at the top of the market.

Do

In 1999, Nike started the NIKEiD project, where customers could create their own shoes. NIKEiD

enabled customers to personalize a pair of selected shoe models using online customization

software. The software led consumers through a step-by-step process where customers could

choose the size and width of their shoes, pick the color scheme to be used, and affix their own 8character personal ID to the product. In the initial stages, the project came up for severe criticism

because of limited selection and availability of models. However, Nike soon increased the scope of

the project by adding shoe models and increasing customization options. The NIKEiD project also

allowed the company to increase its market share by tailoring the product to suit the needs of

customers.

CRITICISMS AGAINST NIKE’S MARKETING

Though Nike was generally thought to be a successful marketing company, it faced several

criticisms for its marketing activities. Some ads, for instance, did not go down well with the target

market. One such ad featured Joanne Ernst, an American tri-athlete and addressed American

women for the first time. The ad spoke about the importance of fitness for working women.

However, it did not go down well with the target group because most working women in America

did not have the time for working out and fitness. They perceived the ad as trying to create a guilt

complex in them for not working-out. The ‘Just Do It’ punch line in the ad, which was supposed to

be a suggestion, also came out too strongly and women did not like the pressure it put on them.

19

AdAsia 2003: Great brands play the role of protagonists: Scott Bedbury, agencyfaqs.com, November 12,

2003.

20

Michaela Lowthian, Marketing Muscle, Willamette Week, November 10, 1999.

8

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

This ad was also one of the last times that the ‘Just Do It’ punch line was verbalized in an ad. The

punch line had, by itself, been criticized quite often, as some people felt that it was too strong and

created a psychological pressure in people to push themselves to achieve more. It was perceived as

too demanding and competitive. Another punch line used by Nike was “I Can”. This replaced ‘Just

Do It’ theme in the late-1990s and was criticized almost as much as its predecessor. Analysts said

that ‘I Can’ instilled an unjustified feeling of capability in people and they were sometimes pushed

to do things that they should not do, even if they could.

Analysts also said that both the punch lines created feelings of inferiority in people who were not

able to do certain things (like working-out or training for a sport), and made them feel guilty. For

instance, a child whose parents were not in a position to afford sports training, would feel left out

and inferior on watching Nike ads and following the punch lines. They said that both the ads

targeted people who had reached the highest level in the hierarchy of needs21 and the only need

and motivation left in them was to do the best they could (self actualization). In the process they

made people, who had to still fulfill physical and material needs, feel inferior.

tC

op

y

It was also felt that overexposure of the Nike brand was not good for the company’s image.

Initially, the company had tried to create the image that the best players wore Nike shoes. It

created an image of exclusivity and a feeling of being special. However, as the company grew, too

many people started wearing Nike shoes and in the process, the exclusivity was lost. Analysts felt

that this could put off an important target market of teenagers and young adults, who sought

exclusivity and chose things that set them apart from the crowd. They said that the brand had

become too common to be thought ‘cool’.

No

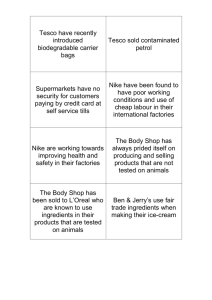

Nike’s practice of using celebrities to endorse its products was also criticized. Analysts said that,

by using celebrities, the company was trying to capture the target market through an appeal to

emotions. People often bought products that they did not need just because their favorite celebrity

was endorsing it. While this was all right for people who could afford it, those who could not, were

left feeling unfulfilled. The company, however, faced maximum criticism for the money it spent

on celebrity contracts. When seen in the light of the wages paid to poor Asian workers in Nike’s

manufacturing facilities, the amounts paid to celebrities seemed unjustified. Analysts felt that it

was not correct for a company (which did not pay even a basic living wage to its workers in Asia)

to pay huge amounts to sports stars who just appeared in ads featuring Nike products.

Do

Analysts felt that there was another disadvantage in using celebrities. When celebrities got into

trouble, it reflected negatively on the company’s image. Nike, which usually sponsored

temperamental stars like Eric Cantona (A Manchester United and England soccer player, who once

kicked a fan during a match), Ilie Nastase (a Romanian tennis player, known for swearing at

umpires) and Shane Warne (an Australian cricketer, who got involved in a match-fixing

controversy), risked the dangers of associating its brand with controversial people. Nike however,

had a history of standing by its endorsers in their time of trouble.

CONCLUSION

Despite criticisms against the company, there was little argument on the point that Nike, was one

of the best recognized brands in the world, notably in the area of sports. So popular was the brand,

that some analysts called Nike, the ‘Goddess of Marketing’. Knight attributed Nike’s success to its

dedication to sport. “Part of our success is that we know who we are. We defined ourselves. It is

our job to provide inspiration and aspiration for everyone interested in sports in the world. We

believe that everyone who has a body is an athlete,” said Knight.22 This commitment to sport made

Nike the biggest sporting company in the world.

21

Abraham Maslow’s theory of motivation, which talks about the five different levels of needs in people and

how they motivate them.

22

Stefano Hatfield, What makes Nike’s advertising tick, The Guardian, June 17, 2003.

9

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION:

1. Nike is one of the most successful companies in the world. Discuss Nike’s marketing

foundations with reference to personal marketing. What was the ‘pyramid of influence’? Was

it a valid assumption on which to base a marketing strategy?

2. Celebrity Endorsements formed a very important part of Nike’s marketing strategy. Discuss

the use of celebrities to endorse Nike products. What was the rationale behind the use of

celebrities and what were the pitfalls in using them?

Do

No

tC

op

y

3. Discuss the various elements of Nike’s marketing strategy. What were the criticisms leveled

against the company? Do you agree that Nike’s punch lines were too demanding and

competitive? What measures would you suggest to Nike to deal with the criticism?

10

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

EXHIBIT I

y

THE SWOOSH SYMBOL

Do

No

tC

op

Source: www.lati.tec.sd.us

11

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

EXHIBIT II

INCOME STATEMENT

PERIOD ENDING

(in thousands of dollars)

31-May-03

31-May-02

31-May-01

Total Revenue

10,697,000

9,893,000

9,488,800

Cost of Revenue

6,313,600

6,004,700

5,784,900

Gross Profit

4,383,400

3,888,300

3,703,900

-

-

-

3,137,600

2,820,400

2,689,700

-

-

(100)

-

-

-

-

-

-

1,245,800

1,067,900

1,014,300

(79,900)

(3,000)

(34,200)

1,165,900

1,064,900

980,100

42,900

47,600

58,700

1,123,000

1,017,300

921,400

382,900

349,000

331,700

-

-

-

740,100

668,300

589,700

Discontinued Operations

-

-

-

Extraordinary Items

-

-

-

(266,100)

(5,000)

-

Other Items

-

-

-

Net Income

474,000

663,300

589,700

-

-

-

$474,000

$663,300

$589,700

Operating Expenses

Research Development

Selling General and Administrative

y

Non Recurring

Total Operating Expenses

Operating Income or Loss

tC

Income from Continuing Operations

op

Others

Total Other Income/Expenses Net

Earnings Before Interest And Taxes

Interest Expense

No

Income Before Tax

Income Tax Expense

Minority Interest

Net Income From Continuing Ops

Do

Non-Recurring Events

Effect Of Accounting Changes

Preferred Stock And Other

Adjustments

Net Income Applicable To

Common Shares

Source: finance.yahoo.com

12

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

EXHIBIT III

MARKET SHARE OF THE 3 MAJOR PLAYERS IN BASKETBALL SHOES IN 2003

COMPANY

Nike

Adidas

Reebok

MARKET SHARE

60%

20%

15%

Do

No

tC

op

y

Source: Compiled from www.oligopolywatch.com

13

Nike – The ‘Goddess of Marketing’

ADDITIONAL READINGS & REFERENCES:

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

y

op

17.

tC

13.

14.

15.

16.

No

10.

11.

12.

Kenneth Labich, Nike vs. Reebok, Fortune, September 18, 1995.

Stanley, T.L. Steve Gelsi, Penny Pegged Next Nike franchise, Brandweek, October 30, 1995.

Randall Lane, You Are What You Wear, Forbes, October 14, 1996.

Jeff Jensen, Marketer of the Year, Advertising Age, December 16, 1996.

In the Vanguard, the Economist, June 5, 1997.

Ronald B. Lieber, Just Redo It, Fortune, June 23, 1997.

Jim Surowiecki, the Trouble With Nike, Marketing, March 23, 1998.

Patricia Sellers, Four Reasons Nike's Not Cool, Fortune, March 30, 1998.

Nike:No Fundamental Change in Sports Marketing Strategy, PR Newswire, October 1,

1998.

Michaela Lowthian, Marketing Muscle, Willamette Week, November 10, 1999.

Eric Ransdell, The Nike Story? Just Tell It!, Fast Company, January 2000.

Louise Lee, Nike tries Getting in Touch with its Feminine Side, BusinessWeek, October 30,

2000.

The Smell of the Swoosh, www.adbusters.org, July/August 2001.

Matthew Boyle, How Nike Got Its Swoosh Back, Fortune, January 24, 2002.

Julia Day, Nike Launches ‘Green’ Trainers, The Guardian, January 25, 2002.

Chris Reidy, Nike Swooshes its way into Key Marathon Advertising Site, The Boston

Globe, March 26, 2002, www.boston.com

Terry Lefton, Nike, Reebok play NFL head games, The Portland Business Journal,

September 16, 2002.

Julia Day, Brand Victory for Nike, the Guardian, February 21, 2003.

Olga Kharif, When to Run With Nike, BusinessWeek, April 18, 2003.

Joe Harwood, A Run for their Money: Nike puts Marketing Muscle into Track Classic,

duckhenge.uoregon.edu, May 19, 2003.

William McCall, Nike Outbids Reebok for LeBron James, The Guardian, May 22, 2003.

Wayne Friedman, Kevin Carroll puts spring in Nike's marketing step, Advertising Age,

June 9, 2003.

Stefano Hatfield, What Makes Nike's Advertising Tick, The Guardian, June 17, 2003.

Julia Day, Nike Stands By its Man, The Guardian, October 30, 2003.

Larry Barrett and Sean Gallagher, New Balance: Shoe Fits, Baseline, November 1, 2003.

AdAsia 2003: Great brands play the role of protagonists: Scott Bedbury,

www.agencyfaqs.com, November 12, 2003.

Stanley Holmes and Faith Arner, A New Game Afoot for Adidas and Reebok, Business

Week, December 5, 2003.

wps.prenhall.com/bp_kotler_mm

Wwwfl.ebs.de

www.lati.tec.sd.us

www.lehigh.edu

www.oligopolywatch.com

www.hoovers.com

finance.yahoo.com

www.fool.com

www.businesseek.com

www.theathletesfoot.com

www.geocities.com

www.trizera.com

www.nike.com.

Do

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

14