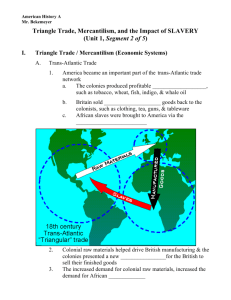

British North america and the atlantic World British North america

advertisement