Press kit - Palazzo Strozzi

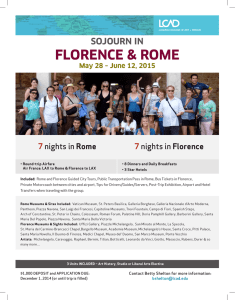

advertisement