Heroic Traits Socratic Seminar

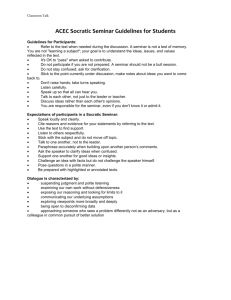

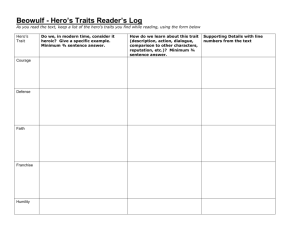

advertisement

Mueller What is a Hero? Socratic Seminar – What can literature teach us about the true traits of a hero? Truth, for the purposes of this discussion, is an idea or understanding that remains constant/on a consistent path of evolution throughout time and across cultures. A hero, for the purposes of this discussion, is a figure that faces challenges and by so doing displays the virtues and traits considered necessary for its survival by a culture. Consequently, if there are in fact true heroic traits, they should be traits that we can find in heroes from any era, from Gilgamesh to the 21st century. In this unit, we’ve read several short fiction and non-­‐fiction narratives dealing with heroes – from the famously archetypal to the pseudonomically obscure. Are there any traits that all of them share and that all of them demonstrate in overcoming obstacles? In short, is there a “true” essential heroic trait? Preparing for the Socratic Seminar: 1. Heroes under examination: Gilgamesh/Enkidu, David, Rama, and Bigfoot. 2. Annotate your background texts: the articles on “Resilience” and “Struggle for Smarts.” I have posted two other articles on the calendar that you may use as supplements, but these two articles are our focus. 3. Create a chart listing 5-­‐7 values you think may be essential for a hero’s success. You must include resilience and grit as two of your traits. Provide a definition of/characteristics of each of the traits. 4. For each trait, provide evidence of the different heroes displaying – or not displaying – that trait. You must include a textual reference – at the very leaset a page #, if not a direct quote – showing where your evidence is found in the text. Make sure that you have specific evidence from the story to back up your stance. Be prepared to reference paragraph number (in shorter essays) or page number (in longer stories) as you offer support for your argument. 5. Prepare at least nine questions you could ask during the course of the seminar. These should be open-­ended questions – that is, questions that can’t be answered with a simple yes-­‐or-­‐no question. These questions should be drawn from the material you’ve gathered and designed to get your classmates talking about the discoveries you’ve made. a. They can be opening questions, questions that introduce a topic and start the conversation rolling. Example: “What actions of Gilgamesh do you think most clearly define him as heroic?” Mueller What is a Hero? b. They can be core questions, questions that ask for interpretation, that draw together traits and characters, or that compare/contrast characters from different texts. Example: “How would Rama respond to Bigfoot’s insistence upon honesty?” c. They can be closing questions, questions that draw conclusions from the evidence we’ve discussed and make connections to the larger world. Example: “Of the three traits suggested, which one would be most pertinent in a world driven by technology?” Please note: all questions should build toward answering the overarching seminar question. Asking “Who wrote ‘Bigfoot’ “ is not pertinent to the seminar; asking “What does Anthony Bourdain seem to value most in Bigfoot’s personality” is. 6. Read over the “Socratic Seminar” guidelines. You will be graded on both your written preparation and your oral presentation. You must speak at least once during the course of the seminar. Participants are graded based on how clearly they connect their argument to the text, as well as how carefully they listen to and respond to other students in the circle. This Socratic Seminar will be held on ___________________________. You should have all your prepared paperwork, as well as the narratives/stories themselves for reference during the seminar. After the seminar, you will turn in all your prepared paperwork (steps 3, 4, and 5). If you miss the seminar, you will need to turn in a 3-­5 paragraph summary of your answer to our guiding question, as well as your prepared paperwork. The summary is due within one week of the seminar’s date.