From Injury to Emancipation Double Consciousness and the

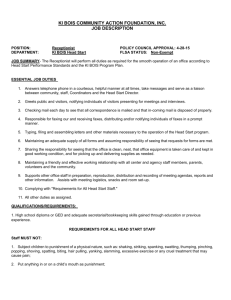

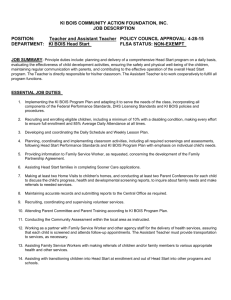

advertisement