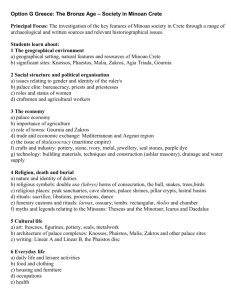

the origin and iconography of the late minoan painted larnax

advertisement