US IMPERIALISM IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY?

advertisement

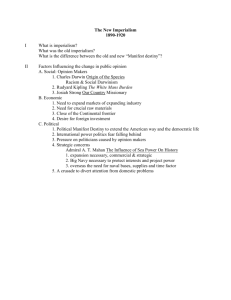

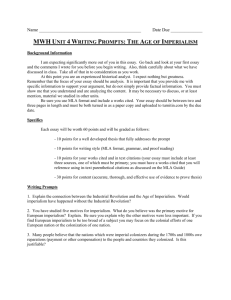

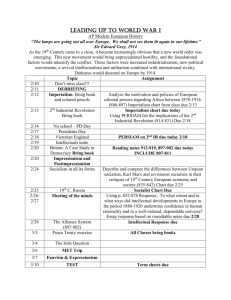

128 AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES US IMPERIALISM IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY? CLARE CORBOULD In recent years there has been a slew of books about the United States with the words ‘imperial’ or ‘empire’ in their titles. This phenomenon is not strictly new. Since the 1890s a variety of both critics and supporters of US actions overseas have characterized those activities as imperial. Currently, however, popular presses and historians alike have created an intersection between the fields of US history and colonial studies.1 Teaching American history when the United States launched its ‘preemptive strikes’ against Iraq in 2003, it was obvious that students were interested in learning about the antecedents of present-day foreign policy. Their curiosity dovetailed nicely with my own interest in histories of empire and postcolonialism. In the first semester of 2005 I offered ‘US Imperialism in the Twentieth Century?’ to second- and third-year students. The course examined whether the foreign relations of the United States during the twentieth century might be considered imperial, and if so, in what ways. The course was weighted toward the analysis of culture, though in lectures I covered broad political trends in foreign policy. One of the advantages of this approach is that of the 220 students, most Australian and some American, almost all were extremely conversant in American popular culture. Their knowledge made for robust discussion in class and they seemed to enjoy having to expand and revise their views of culture they had previously judged only on the basis of whether or not they liked it. I designed the course around four main themes: • competing theories of empire and imperialism, and the usefulness and difficulty of applying these concepts to the United States; • the principles that governed foreign policy during this period, and how these were shaped by American domestic culture and by Americans’ expectations of the role of their government, including American anti-imperialism; • political, economic, social and cultural forms of domination and how these transformed societies overseas; and • the remaking of American culture over the twentieth century as a result of actions overseas. Students attended two lectures and one tutorial each week for thirteen weeks. Each of these classes picked up in some way on one or more of the AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES 129 themes. I made this explicit to the students by using lecture outlines and tutorial questions that were also available on the course website (http://teaching.arts.usyd.edu.au/history/hsty2067). A mix of primary and secondary materials in a course reader formed the basis of tutorial discussions. I intended that these discussions would set an example of how to actually do history, and thereby lay the groundwork for the students’ written assessments. We began the course by considering how people have defined ‘empire’ and ‘imperialism’ and started to address the issue as to how useful these concepts are when applied to the operation of US power. In the first substantial tutorial we read Hannah Arendt’s essay ‘The Imperialist Character’ and excerpts from The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951). This was a successful choice of opening material. Throughout the semester the students recalled Arendt’s descriptions and used them as one way to assess the character of American foreign policy. In that opening tutorial we also read Anne McClintock’s ‘The Angel of Progress: Pitfalls of the Term “Post-colonialism.”’2 It was less successful. If this failure was initially difficult to gauge, by the end of the semester it was clear that I ought to have stressed much more carefully, from the outset, the value of postcolonial approaches. In particular, I should have shown the need for students to assess the results of US actions from non-American perspectives, especially those in countries and regions affected. The need to do so was especially clear when we looked at critiques of the American claim to be ‘spreading democracy.’ Many students were not able to grasp why some view this ideology, and the actions that flow from it, as imperial. After a single lecture on US imperialism before the twentieth century, we plunged in and proceeded pretty well chronologically. Though the scope of the course was broad, when I teach it again I will extend the time period covered. One of the aims of the course was to problematize the longstanding sense that the 1890s was a watershed decade in which American policy changed. It was hard to present the argument that overseas expansion was in many ways the continuation of the policy of continental expansion without dealing in a more concrete fashion with the details of the nineteenth century. The student evaluations conducted at the semester’s end demonstrated the students’ confusion. While some wanted more material on the nineteenth century, others could not see its place in a course with the title I gave this one. In examining the Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino war, the students were able to see the importance of analyzing the relationship between domestic culture and international relations. We focused in particular on ideologies of 130 AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES gender and race that shaped how those conflicts took place and how they were understood by Americans at the time. I showed the students a great 30minute film, Savage Acts: Wars, Fairs and Empires 1898-1904. It uses an array of evidence about the wars and about the World’s Fairs of 1893, 1901 and 1904, in order to canvas American attitudes to race during those years of expansion.3 The varied contemporary responses to the annexation of the Philippines also gave the students the chance to begin to explore the tradition of anti-imperialism in the United States. We explored similar themes when learning about the interaction between American missionaries, American government officials, business interests during the push into China. In addition, I used the excellent work of Matthew Frye Jacobson to introduce the importance of the history of immigration into the United States to understanding foreign relations.4 Over the following couple of weeks, the lectures outlined Theodore Roosevelt’s policy to speak softly and carry a big stick, Wilsonianism and internationalism, isolationism, and Franklin Roosevelt’s ‘Good Neighbor’ policy during the 1930s. Drawing on my own research, we examined the occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934. That occupation and similar episodes, require us to revise the idea that the United States was ‘isolationist’ during the years between 1919 and 1941. Langston Hughes’s memoir of his trip to Haiti proved to be of great value here. Hughes’s critique of the American occupation, and of American racism within and without the United States, illustrated the failures of the ‘American Dream’ that was used to justify the occupation. In addition, students read Mary Renda’s account of the transformation of American culture as a result of the Haitian occupation, a history that complicates any simple understanding of isolationism at the time. Anti-imperialism surfaced again when we examined contemporary critiques by Randolph Bourne and others of the United States’ involvement in World War I. In lectures I outlined the efforts by Ernest Gruening, former editor of The Nation and future senator, at anti-imperialist reform in Puerto Rico between 1934 and 1939.5 In all of these instances our discussions canvassed the variety of reasons that people might criticize foreign policy that they saw as imperialist. Some critics were concerned with the deleterious effects of American foreign policy on those in the countries involved. Others were more concerned with the effects that such policies would have on the American nation, whose exceptionalism they characterized as based on its aloofness from the rest of the world. The latter strain was certainly evident in escalating calls to remain isolated during World War II, demonstrating that not all isolationists were anti- AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES 131 imperialist. I showed the students Frank Capra’s film, War Comes to America (1945), volume seven of the Why We Fight series. The film is a fascinating piece of evidence for exploring mainstream ideals as to the nature of American society. To show how pervasive these ideas are, we also watched part of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998), a film most students had already seen. The way that Spielberg frames that film with an old man recollecting his experiences, his face washing in and out with that of the American flag, allowed us to explore how particular narratives about American foreign policy have shaped the national consciousness in the present-day. We used these studies to revise the longstanding sense that World War II was a ‘good’ war. The debate ended with a discussion of the internment of Japanese- and German-Americans, and the dropping of the two atomic bombs on Japanese cities. In lecturing on the second half of the century, I turned more explicitly to examining overt conflicts and covert operations overseas. These included the Korean War, the Vietnam War, interventions in Africa, South America, Central America, Afghanistan and the Middle East. Bill Chafe, from the University of North Carolina, recontextualized these case studies in two guest lectures. In one, he lectured on the relationship between the Cold War and the civil rights movement. The second lecture argued for the similarities between the wars in Vietnam and Iraq. In tutorials we examined the transformation of postwar European culture, using official documents such as the Marshall Plan, cartoons published in Europe, and memoirs by Europeans who were teenagers at the time. We also discussed the changes wrought in American culture during this time, watching Atomic Cafe (1982), and reading Lizabeth Cohen and others. As the semester wound up, the final tutorials were devoted to examining the ‘imperialist’ dimensions of aid, the failure to intervene early in Rwanda, the relationship between globalization and imperialism. Lastly, we scrutinized the efforts to stymie criticism of the current administration’s war in Iraq. In the final class, I also set a ‘counterfactual’ history of recent years, in which President Al Gore responds to the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center by convening nation-wide therapy sessions. The final tutorial demonstrated that the students certainly had a much fuller understanding of America’s involvement in Iraq than they had at the beginning of the semester. Many held firm to their original belief that the war is ‘all about oil,’ but they also talked knowledgably about the historical contexts for various positions vis-à-vis the war. 132 AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES The assessment tasks were sequential. Early in the semester the students submitted a 500-word review of a recommended book or film that dealt in some way with one or more themes of the course. This task was designed to introduce them to the analysis of primary sources and to the tools, particularly, of cultural history. At the end of week four, students also submitted a 500-word essay proposal on a topic of their own choosing. I gave them guidelines as to how to find primary material to analyze and on how to formulate a question. The course outline included extensive lists of recommended reading. Within a fortnight, the tutors and I provided detailed written feedback on these proposals and met with probably half of the students to discuss their ideas. In the end-ofsemester evaluations, many students expressed their surprise at finding staff, especially the tutors, Cam MacKellar and Katy Nebhan, so interested in their work. At the close of the ninth week of semester, the students submitted the essay. This process was a qualified success. While most of the students came up with interesting and appropriate questions, some floundered. This was true especially of those students in their first semester of second-year. Next time I run the course I will provide essay questions. I will also provide more pointers for the large number of students who were interested in writing about the relationship between media, government policy and public opinion, but struggled to find enough appropriate sources in the time available. Having said that, many, perhaps even most students relished the chance to pick their own topic and to spend several weeks researching and developing an argument. The best essays ranged in topics, including Woody Guthrie’s music, comic books in the 1950s, novels about Boy Scouts by G. Harvey Ralphson, Edward Steichen’s ‘The Family of Man’ exhibition at the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1955, writings by American missionaries in China and Korea, and the cultural imperialism of the Rockefeller Foundation in the 1960s and 1970s. Partly because sources on American topics were easier to get hold of than those on, say, Guatemala or even Vietnam, the best essays addressed the fourth theme of the course: the remaking of American culture over the twentieth century as a result of actions overseas. As the final component of their written assessment, the students undertook a take-home examination. One section of the exam asked the students to use examples from the first half of the twentieth century to tackle a question about the usefulness of analyzing culture to understand foreign relations. In answering this question it was clear that many students had not grasped the AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES 133 distinction between a cultural history of imperialism and cultural imperialism. These students gravitated toward any evidence specifically connected to the government. For example, many wrote about Disney films made in the late 1930s and 1940s, which were funded by the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs.6 In general students found it more difficult to analyze standard Hollywood fare. When writing their film reviews, many who chose to look at Black Hawk Down (dir. Ridley Scott, 2002) concentrated on the fact that the hardware for the film was provided by the American military. They looked, in other words, for evidence that these films were propaganda, rather than analyzing them as cultural artefacts that reflected as well as influenced popular attitudes to foreign policy and imperialism. Their error is a common enough one, based on the idea that people consume culture passively. In future the opening tutorials will be devoted to setting up the methodological approach of the course as well as the framework for understanding the content. Many students had a sense that culture, while interesting, is windowdressing, and that, to mix metaphors, the real roots of imperial foreign policy lie in economics, capital ‘P’ politics, and diplomacy. When asked what they would change about the course, one student responded: ‘While the cultural history was interesting, I found it largely irrelevant. So we could sit around for hours in tutorials and talk about black people and phallic symbols and bombshell women and protest music and McDonalds in India but it didn’t get us anywhere. It didn’t prove or demonstrate anything to us beyond what we already knew. I want more investigative political and economic history.’ And yet the same student wrote on the same sheet on paper that the most important thing s/he learnt was ‘The concept of racism and its influence on US foreign policy.’ The contradiction between these comments shows both the importance of the material I’m teaching and the challenge of teaching it. Clearly I have some work to do selling the importance of cultural analysis to the students. In the first instance I have renamed the course ‘Politics and Cultures of US Imperialism.’ The second examination question required the students to draw on material from the second half of the century. I asked them to use this to address the proposition that the ‘global power’ of the United States was unique and exceptional, and characterized by its opposition to Nazi and Soviet imperialism. For all of our debate over the course of the semester as to whether ‘imperialism’ was an appropriate way to describe the operation of US power overseas, the students mostly agreed with the proposition. (I have since learnt that whenever students are faced with responding to a quotation, they tend to agree with it.) The question ought to have been more specific, something such as: Americans often claim that their ‘global power’ is unlike 134 AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES that of other nations and empires. Drawing on events of the second half of the century, do you agree? Though I will thoroughly overhaul the course the second time I run it, this was an extraordinarily rewarding class to teach. The students were extremely interested in the material. Because they felt that this was an important subject with direct relevance to their lives, they were lively in class and came up with some creative and fascinating research topics. US Imperialism in the Twentieth Century? Description This unit examines: the U.S. overseas in the 20th century; political, economic, social and cultural forms of domination and how these transformed both those societies overseas and the U.S. itself; the value of applying the concept of imperialism to U.S. power; the historiography of the U.S. in the world. What you will learn Themes: By the end of this course you will have a broad understanding of the following themes: • competing theories of empire and imperialism, and the usefulness and difficulty of applying these concepts to the United States; • the principles that governed foreign policy during this period, and how these were shaped by American domestic culture and by Americans’ expectations of the role of their government, including American anti-imperialism; • political, economic, social and cultural forms of domination and how these transformed societies overseas; and • the remaking of American culture over the twentieth century as a result of actions overseas. Skills: Analytical skills: • in reading primary documents including autobiographies, court records, interviews, images, film, advertisements, travel narratives, diaries and novels. You will learn to consider what these sources tell us about the past and how to read them as different types of evidence, assessing their strengths, weaknesses and generic characteristics; • in reading historians’ interpretations and assessing critically their arguments in context with the primary material you are reading and AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES 135 in relation to other historians’ interpretations. In other words, you will learn about and engage with the historiographical context of the field. Skills in verbal and written communication: • tutorials give you the opportunity to develop your spoken and listening skills and encourage you to learn to participate in scholarly debate; • the tutorial presentation challenges you to present a very short summary of the set readings and to ask questions that provoke discussion; • the book/film review in which you analyze one specific source to explore the broader themes of the course; • the essay proposal enables you to develop skills in organization as you are required early in the semester to present a brief summary of the sources you will use and the historiographical debates with which you will engage; the essay proposal, like • the essay of 3000 words, require that you find evidence on which to base your argument as well as locate interpretations written by other historians. You will develop your research skills, writing skills and learn to sustain an argument at length; • the take home examination allows you to reflect on the themes of the course and to demonstrate your understanding of the course as a whole. Skills in organization: • in managing your time so that you attend lectures, tutorials, read and think about the material prior to class and meet your deadlines. Assessment Tutorial participation Film/book review Essay proposal and annotated bibliography Essay Take-home examination Course schedule and required readings Lecture outline: Introduction Week 1 Introduction: Competing theories of imperialism Governing principles of twentieth century foreign policy 136 Week 2 AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES US Imperialism before the twentieth century The Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War Week 3 Common Week Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Film: Savage Acts: Wars, Fairs and Empires 1898-1904 China and the Open Door No classes Roosevelt’s Big Stick Wilsonianism and Internationalism – Glenda Sluga, Associate Professor, Department of History Isolationism America goes to the Caribbean. Case study: Haiti Good Neighbors? How to Read Donald Duck Rescuing the world, again Dropping bombs “The American Century”? The Cold War begins Essay writing tips Korean War 1950-1953 Week 9 Week 10 Covert action under Eisenhower Film: Atomic Cafe, dir. Jayne Loader and Pierce Rafferty (1982) Cold War and Civil Rights – William H. Chafe, Alice Mary Baldwin Professor of History, Duke University Decolonization in Africa Week 11 Week 12 Vietnam & Iraq – William H. Chafe Central America: Carter, Reagan, Bush The US does UNESCO: Cultural imperialism in American politics – Charles Fairchild, Lecturer, Conservatorium of Music Winning (recovering from?) the Cold War: Clinton AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES Week 13 137 Afghanistan, the Second Gulf War Wrap Up: exam prep and essays returned Tutorial readings: Week 2: Introduction to the course and the here and now Michael Ignatieff, “Why Are We in Iraq? (And Liberia? And Afghanistan?)” New York Times Magazine, Sept. 7, 2003. I included this article as a way to begin discussion with contemporary issues, which were very much on the minds of most students. Our discussion was guided by these questions: What are the antecedents for America’s actions in Iraq? Is there anything unique about them? Recently, Jonathan Raban suggested that Ignatieff is the Bush administration’s “in-house philosopher.” What prompted Raban’s comment? Do you agree? Week 3: Defining the “Imperialist Character” Hannah Arendt, “The Imperialist Character,” Review of Politics, vol. 12, no. 1 (Jan. 1950), 303-320. Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 3rd. ed. (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1966), 158-161, 170-175, 183-184. Anne McClintock, “The Angel of Progress: Pitfalls of the Term ‘Postcolonialism,’” (1992) reprinted in Colonial Discourse and Post-colonial Theory: A Reader, ed. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (New York: Harvester, 1994), 291-304. Week 4: An American Exception? Paul A. Kramer, “Empires, Exceptions and Anglo-Saxons: Race and Rule Between the British and US Empires, 1880-1910,” Journal of American History, vol. 88, no. 4 (March 2002), 1315-1353. Primary: Frederick Douglass, “Introduction,” and F. L. Barnett, “The Reason Why,” in The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition, ed. Robert W. Rydell (1893; Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 7-16, 65-81. Assessments due: 500-word film/book review 500-word essay proposal with annotated bibliography 138 AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES Week 5: Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War Amy Kaplan, “Black and Blue on San Juan Hill,” in Cultures of United States Imperialism, ed. Amy Kaplan and Donald E. Pease (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 219-236. Primary: Theodore Roosevelt, 1899, from The Strenuous Life: Essays and Addresses (New York: The Century Company, 1900). Argentina’s Foreign Minister Luis Drago Condemns the Collection of Debts by Force, 1902. The Panama Canal Treaty Grants the United States a Zone of Occupation, 1903. President Rafael Reyes Enumerates Colombia’s Grievances Against the United States, 1904. The Roosevelt Corollary, 1904. Rubén Darío, “To Roosevelt,” 1905. Primary online: Jim Zwick, ed., Anti-Imperialism in the United States, 1898-1935, http://www.boondocksnet.com/ai/index.htm Have a good look around the site. You might like to start with “‘The White Man’s Burden’ and Its Critics”: http://www.boondocksnet.com//ai/kipling/ The Spanish-American War in Motion Pictures, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/sawhtml/sawhome.html Week 6: The First Red Scare Kim E. Nielsen, “What’s a Patriotic Man to Do? Patriotic Masculinities of the Post-WWI Red Scare,” Men and Masculinities, vol. 6, no. 3 (Jan. 2004): 240-253. William E. Cain, “From Liberalism to Communism: The Political Thought of W. E. B. Du Bois,” in Cultures of United States Imperialism, ed. Amy Kaplan and Donald E. Pease (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 456473. Primary: Helen Keller, “Strike Against War,” (1916). John Reed, “Whose War?” (April 1917). “Why the IWW Is Not Patriotic to the United States” (1918). Emma Goldman, Address to the Jury in U.S. v. Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman (July 9, 1917). Two Antiwar Speeches by Eugene Debs (1918). Randolph Bourne, “The State,” (1918). Week 7: The US, Latin America, and the Caribbean during the Interwar Years AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES 139 Louis A. Pérez, Jr., “Dependency,” in Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations, ed. Michael J. Hogan and Thomas G. Paterson, 2nd. Ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 162-175. Mary A. Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915-1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 185-228. Primary: Langston Hughes, “In Search of Sun,” I Wonder As I Wander: An Autobiographical Journey (1956; New York: Hill and Wang, 1984), 3-37. Week 8: Democratizing the Enemy Reed Ueda, “The Changing Path to Citizenship: Ethnicity and Naturalization during World War II,” in The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II, ed. Lewis A. Erenberg and Susan E. Hirsch (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 202-216. Primary: Yuri Kochiyama, “Then Came the War” (1991). Primary online: Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project: http://www.densho.org/ A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution: http://www.americanhistory.si.edu/perfectunion/non-flash/index.html Week 9: The Americans are Coming! The Americans are Coming! Rob Kroes, “Americanization: What Are We Talking About?,” If You’ve Seen One You’ve Seen the Mall: Europeans and American Mass Culture (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 162-178. Primary: Reinhold Wagnleitner, “Foreword to the American Edition” and “Introduction,” Coca-Colonization and the Cold War: The Cultural Mission of the United States in Austria after the Second World War, trans. Diana M. Wolf (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994) ix-xiv, 17. Primary online: “For European Recovery: The Fiftieth Anniversary of the Marshall Plan,” at the Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/marshall/ and especially: o George C. Marshall, Speech at Harvard, June 5, 1947: http://lcweb.loc.gov/exhibits/marshall/m9.html 140 AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES Jo Spier, The Marshall Plan and You (1949): http://lcweb.loc.gov/exhibits/marshall/mp1a.html o William Averell Harriman’s Album: The Marshall Plan at the Mid-Mark: http://lcweb.loc.gov/exhibits/marshall/mal1a.html For audiovisual material see also "Marshall Plan Home Page" of the US Agency for International Development: http://www.usaid.gov/multimedia/video/marshall/ o Assessment due: 3000-word essay Week 10: Cold and Hot Wars at Home Lizabeth Cohen, “Commerce: Reconfiguring Community Marketplaces,” A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (New York: Knopf, 2003), 257-289. Elaine Tyler May, “Explosive Issues: Sex, Women, and the Bomb,” Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1988), 92-113. Chester J. Pach, Jr., “And That’s the Way It Was: The Vietnam War on the Network Nightly News,” in The Sixties: From Memory to History, ed. David Faber (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 90118. Week 11: Humanitarian Intervention? Alison Des Forges, “Learning From Disaster: U.S. Human Rights Policy in Rwanda,” in Implementing U.S. Human Rights Policy: Agendas, Policies, and Practices, ed. Debra Liang-Fenton (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2004), 29-50. Jon Western, “The Sources of Humanitarian Intervention,” International Security, Vol 26, no. 4 (Spring 2002), 112-141. Cynthia Enloe, “The Politics of Constructing the American Woman Soldier,” The Morning After: Sexual Politics at the End of the Cold War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 201-227. Primary: Nuha Al-Radi, Baghdad Diaries: A Woman’s Chronicle of War and Exile (New York: Vintage Books, 1998), 9-31, 37-38, 46-49, 53-60. Watch, if you have time: Black Hawk Down, dir. Ridley Scott, (2002) Control Room, dir. Jehane Noujaim (2004) AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES 141 Hotel Rwanda, dir. Terry George (2004) Week 12: Stuart Hall, “The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity,” (orig. 1991), in Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation, and Postcolonial Perspectives, ed. Anne McClintock, Aamir Mufti and Ella Shohat (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 173-187. Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, “From the Imperial Family to the Transnational Imaginary: Media Spectatorship in the Age of Globalization,” in Global/Local: Cultural Production and the Transnational Imaginary, ed. Rob Wilson and Wimal Dissanayake (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 145-170. Watch, if you have time: Life and Debt, dir. Stephanie Black (2001) Week 13: Judith Butler, Preface and “Explanation, Exoneration, or What We Can Hear,” Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004), xi-xxi, 1-18. David Frum, “The Chads Fall Off in Florida,” in What Might Have Been: Leading Historians on Twelve ‘What Ifs’ of History, ed. Andrew Roberts (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2004), 179-188. Final assessment: take-home examination ENDNOTES 1 eg. Amy Kaplan and Donald E. Pease, (eds.)., Cultures of United States Imperialism, Duke University Press, Durham, 1993; Ann Laura Stoler, ‘Tense and Tender Ties: The Politics of Comparison in North American History and (Post) Colonial Studies,’ Journal of American History, vol. 88, no. 3, December 2001 pp. 829-865 and roundtable discussion, pp. 866-897. 2 Anne McClintock, ‘The Angel of Progress: Pitfalls of the Term “Post-colonialism,”’ (1992), reprinted in Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman, (eds.), Colonial Discourse and Post-colonial Theory: A Reader, Harvester, New York, 1994, pp. 291-304. 3 Savage Acts: Wars, Fairs and Empires 1898-1904, American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning, the City University of New York, 1995. 4 Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917, Hill and Wang, New York, 2000. 5 Robert David Johnson, ‘Anti-Imperialism and the Good Neighbour Policy: Ernest Gruening and Puerto Rican Affairs, 1934-1939,’ Journal of Latin American Studies 29, 1997, pp. 89110. 6 See Julianne Burton, ‘Don (Juanito) Duck and the Imperial-Patriarchal Unconscious: Disney Studios, the Good Neighbor Policy, and the Packaging of Latin America,’ in Andrew Parker et al (eds.), Nationalisms and Sexualities, Routledge, New York, 1992, pp. 21-41; Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart, How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic, trans. David Kunzle, International General, New York, 1975.