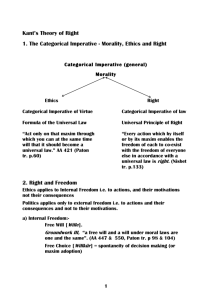

Kant's Analysis of Obligation

advertisement