Civil Society in Vietnam: A Comparative Study of Civil Society

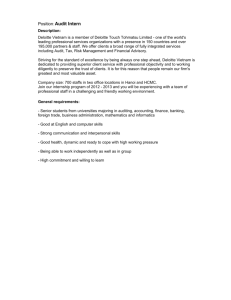

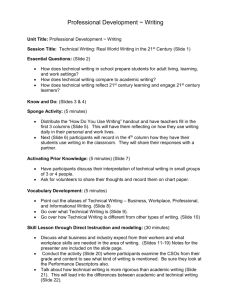

advertisement