Kellogg 2013 Annual Report - i

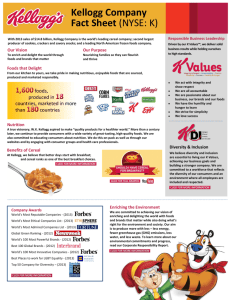

advertisement