Content Analysis and Gender Stereotypes in

advertisement

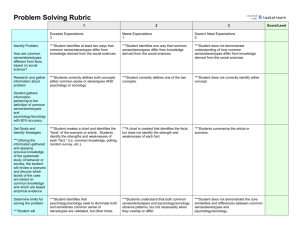

Content Analysis and Gender Stereotypes in Children's Books Author(s): Frank Taylor Source: Teaching Sociology, Vol. 31, No. 3, (Jul., 2003), pp. 300-311 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3211327 Accessed: 03/07/2008 11:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=asa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. http://www.jstor.org CONTENTANALYSISAND GENDER STEREOTYPESIN CHILDREN'SBOOKS* This article deals with gender stereotypes in popular children's books. I propose an exercise in which students use content analysis to uncover latent gender stereotypes present in such popular books as those by Dr. Seuss. Using a coding frame based on traditionalgender-role stereotypes, I assign students to small groups who then undertakea close analysis of selected children's books to see whether or not traditionalgender-role stereotypes are apparent. Students examine the text, symbols, characters, use of color, and major themes in each book. In this article, I briefly review the theoretical underpinnings of the exercise, offer a brief summary of content analysis, and outline the delivery of the exercise, its learning goals, and major discussion points. Througha take-home assignment, students are asked to articulate the manner in which gender stereotypes may be perpetuated by the media. Additionally, students are encouraged to think about the ways in which their own gender identities have been shaped by the media. Actual student comments are used throughout to highlight the majordiscussion points. FRANKTAYLOR EdinboroUniversityof Pennsylvania themselvesas membersof various social categories, includingcategoriesrelated to gender,social class, or race and ethnicity, and to thinkaboutthe ways in whichtheir lives have been shapedand influencedby membershipin those groups. Perhapsthe most basic social status is that relatedto gender.Societymaintainsa differentset of normativeroles for women and men, and requiresof them differentresponsibilities andkindsof work.One'sexpectedopportunitiesandoutcomesin life correlatestrongly withgender. One method of helping students learn aboutgenderstereotypesand gettingthem interestedin sociologyin generalis to use the tools of qualitativeanalysis (Walzer 2001). The exercisedescribedhere consists of a content analysisof children'sbooks which contain many common stereotypes "*Pleaseaddress all correspondence to the relatedto gender.Almostany type of chilauthor at Department of Sociology, Edinboro dren'sbook can be used. Studentsperform University of Pennsylvania, Edinboro, PA a contentanalysisof gendermessagesin the 16444; e-mail: ftaylor@edinboro.edu. books by using a codingframespecifically Editor's note: The reviewers were, in for the purpose.Using the techdeveloped M. Linda Art order, Grant, Jipson, alphabetical described here, studentsread and niques and J. Allen Williams. ONE OF THEMOSTdifficult tasks we face whenteachingintroductory coursesin sociis students that society ology convincing in a role their behavior plays large directing and shapingtheirlives. Studentssteepedin the ideologiesof individualism andmeritocmuch to racy prefer view theirbehavioras a matterof choice and outcomesin life as congruentwith their unique talents and skills. For instance,when it comes to genderedbehavior,manystudentsare inclined to believe that differentialoutcomesin life for womenand men are due to naturalor innate differences(particularlydifferences relatedto biology)ratherthanthe processes of socializationand social forces which might be suggested by using their (Mills 1956). "sociologicalimagination" Thus, students must learn to identify Teaching Sociology, Vol. 31, 2003 (July:300-311) 300 CONTENT ANALYSIS AND GENDER STEREOTYPES examinethe books and record their findings, payingparticularattentionto charactersandthemesthatare stereotypical. First I discuss theoreticalbackgroundto the exercisein relationto languageandgender codes. Next, I brieflyreviewthe literature relatedto gender stereotypesin children'sbooksandreviewthe learningobjectives of the exercise and what previous learningstudentsshould have masteredin orderfor the exerciseto be effective. This is followed by a brief review of content analysis.I thendiscussthe exercisedelivery andsomeinstructions on how to carryit out successfully.Finally, I bringup some useful pointsof discussionthat can follow the exercise.This articlecontributesto the present literatureon genderstereotypesby presentingactualstudentobservationsand reflections. THEORETICALBACKGROUND 301 pressionof the generalizedother,andhence of femalenessand maleness (Bem 1981; 1983;Mead1934). By age seven, andperhapsas earlyas age four, childrenbeginto understand genderas a basic componentof self. The literature affirmsthat many masculineand feminine are not biologicalat all; they characteristics are acquired.Genderschema theory, for instance,suggeststhatyoungstersdevelopa sense of femalenessandmalenessbasedon gender stereotypesand organizetheir behavior around them (Bem 1981, 1983, 1984; Eagly and Wood 1999). Children's books may be an importantsourceof gender stereotypesthat childrenuse to help organizegenderedbehavior. An interestingaspect of ideology, and genderideologyin particular,is thatpeople practiceit (Taylor 1998). Ideologicalmessages aboutgenderare embeddedthroughout our culture,andwhen womenand men use them as standardsof comparisonto makejudgmentsaboutthemselvesor about others, we may say that they are "practicing" genderideology.Genderideology is internalizedas a systemof signs; in other words, a code. For example, when trying to emulate cultural standardsof beauty,womenmay use cosmetics,certain styles of dress, and even certaincolors in order to alter their appearance.The same may be said for men. Peoplemay not even be awarethattheirperceptionsaboutreality and their place in it are constantlystructuredin an ideologicalmanner(Heck1980). This exerciseattemptsto help studentsuncover the gendercode and thinkaboutthe waystheirlives havebeenstructured by it. Languagesets the stagefor the development of self-conscious behavior and thought. Throughlanguageand interaction,children acquire a social self (Mead 1934). Language allowshumansto make sense of objects, events, andotherpeople in our environment. Indeed, it is the mechanism throughwhich humansperceive the world (Sapir1929; 1949; Whorf 1956). As childrenlearnhow to read, they are exposedto the culturalsymbols containedin books. Given the assumptionthat languageshapes andconditionsreality,thenit mightbe useful to ask what childrenmight be learning aboutgenderwhentheylearnhow to read. Children'sbooks presenta microcosmof ideologies, values, and beliefs from the dominantculture,includinggenderideoloLITERATUREREVIEW and In other when chilwords, gies scripts. drenlearnhow to readthey are also learn- Children'spre-schoolbooks are an imporing aboutculture.Learningto read is part tant culturalmechanismfor teachingchilof the process of socialization and an important mechanism through which culture is transmittedfrom one generation to the next. For example, children may use the gender scripts and ideologies in these books when they are role playing and forming an im- dren gender roles. A 1972 study of awardwinning children's books discovered that women and girls were almost invisible. Boys were portrayedas active and outdoorsoriented, while girls stayed indoors and behaved more passively; also, men were TEACHING SOCIOLOGY 302 leadersandwomenfollowers(Weitzmanet al. 1972). This researchwas replicatedin 1987, and the researchersconcludedthat althoughsome improvementsin roles for women had taken place, the charactersin the bookswereportrayedin traditionalgender roles (Williamset al. 1987). The 1987 researchfound a majorityof the female charactersshared no particularbehavior, girls in the books failed to expressany career goals, female role models were lacking, and male characterswere still portrayedas more independent.More recent research, based on the same Caldecott children'sbooks, foundthat Award-winning women were still portrayedin traditional gender roles usually associated with the householdandtoolsusedduringhousework, whereasmaleswere non-domesticandassotools and ciated with production-oriented artifacts(CrabbandBielawski1994). However, otherresearchconductedin the 1990s suggests that the traditionalportrayalof womenin children'sbooksis givingway to a moreegalitarian depictionfor bothwomen andmen(Clark,Lennon,andMorris1993). This certainlysuggests that the issues are farfromsettledandrequiremoreresearch. LEARNINGOBJECTIVES In orderto successfullyachievethe learning objectivesof the exercise, some previous topics should have been fully addressed, includingsocialization,culture,and gender inequality.The following learning objectives are derivedfrom the theoreticaldisof languagein the cussionof the importance of socialization: process 1. Demonstratethat gender ideology is embeddedin popularchildren'sbooks. 2. Uncoverthe dimensionsof genderideology presentin the books throughthe use of contentanalysis. 3. 4. Connect the gender ideology in children's books to gender inequalities related to work, occupation, income, and education. Discuss whether the books are simple reflections of innate gender differences or whetherthey actuallyhelp produce genderstratification. and 5. Facilitatea discussionon patriarchy sexism. CONTENTANALYSIS AND EXERCISEDESIGN The exercise relies on contentanalysis-a strategyfor collectingandanalyzingqualitative data throughthe use of an objective codingscheme(Berg2001). Thisdiscussion is intendedto assist instructorsin carrying out a simple content analysis and is not meantto be a thoroughanalysisof methodology. The discussionwill be restrictedto the aspectsof contentanalysisnecessaryto carryout the exercisein a meaningfulfashion. A contentanalysisexaminesthe artifacts of materialculture associatedwith social These artifactscan include communication. writtendocumentsor otherformsof social communicationsuch as children'sbooks, television programs, photographs,magazines, or music recordings.The methodology is useful for inferringmanifestand latent content by systematicallyand objectively examiningthe messagescontainedin the artifact(Abrahamson 1983; Berg 2001; Holsti1968; 1969;Selltizet al. 1967). SamplingStrategy A numberof standardsamplingprocedures can be adaptedfor use in a contentanalysis. However,purposivesamplingis best suited for this exercise (Berg 2001). In a purposive sample, the researcherdraws upon his or her expertiseto select a samplethat exemplifies certain characteristicsof the populationto be studied.Since the goal of the exerciseis to demonstratethat cultural messages about gender are embeddedin children'sbooks, a purposivesamplebased upon an ideal type is acceptable. In this case an "ideal type" is a genera of books in which gender stereotypes are known to exist. For example, some researchers have used Caldecott Award books for the obvious reason that if gender stereotypes are found CONTENTANALYSISAND GENDERSTEREOTYPES 303 in award-winningchildren's books, progress toward gender equality is probably lackingthroughoutthe genre of children's literature. Prior to conductingthe exercise, I ask studentsto write out a list of children's books they are familiarwith. Dr. Seuss is the most frequentlymentionedchildren's book series. The BerenstainBearsand Disney series are also popular,along with a host of other children'sbooks. Out of a populationof 1,357 studentsat four separateinstitutionswho completedthe exercise in my classes over a five-year period of time, 88 percentindicatedthat they were familiarwith the Dr. Seuss series and 71 percentwere familiarwith the Berenstain Bears. This sampleis, therefore,not a representativesampleof booksactuallyreadby any in particulargroupof studentsparticipating the exercise. However, since the exercise thatgenderstereotypes seeksto demonstrate were actuallypresent in the books many studentsreporthaving read as children,it seems, on the face of it, that these books are acceptablefor analysis. Rather than drawinga sampleof books from each series, I purchasedthe entire collections. When I conductthe exercise, I ask each group of studentsto select a book they mightreadto theirchild. In fact, manystudents do report that their selection was basedon a book they were familiarwith as a child or, in the case of some nontraditional students,a book they had actually purchasedandreadto theirchildren. contentis not arbitrary(Berg 2001). The criteriaof selectioncan yield eitherquantitative or qualitativedata; quantitatively, tally sheets can be used to determinethe frequencyof certainelementsin the message. Qualitatively,the studentscan examine the ideologies, symbols, and themes embeddedin the messages and write out summariesof their findings. In this exercise, the criteriafor selectionare basedon traditionalstereotypesaboutgender,usually presentedas a genderdichotomy,and both quantitativeand qualitativeapproacheswill be used. count for variations in messages, explicit enough so that the analysis can be easily replicated, and should reflect the relevant aspects of the messages. Additionally, the criteria of selection should be applied consistently so that inclusion or exclusion of A content analysis can proceed in either an inductive or a deductive manner or some mixture of both (Strauss 1987). If the instructorhas the time to devote to an inductive approach, students start by examining the message in detail and seek to identify ManifestandLatentContent Manifest content in an artifactof social communicationrefers to elementsthat are physicallypresentandcan be countedaccurately.For example,studentscan countthe numberof male or female role models in the books. Additionally,the number of womenin rolesoutsideof thehouseholdcan be countedor the numberof womenin leadershiproles, andso forth. Latent content, on the other hand, requires an interpretivereadingby the researcher, who interrogatesthe symbolic meaningof the datain orderto uncoverits deep structuralmeaning(Berg2001). Obviously, a contentanalysisof latentmessages is moredifficultto achieve.Whenemploying a latentanalysis,the researchershould use corroborative techniques,such as using coders or providingdetailed independent from the data, which supportthe excerpts statedinterpretations. A rich latentanalysis not be in feasible one class period,but may students should be Criteriaof Selection encouragedin the atThe issue of exactly which elementsfrom tempt.Also, a latentanalysismaybe approthe bookswill be analyzedrefersto the cri- priatefor a take-homeexercise, which the teriaof selection;in this exercise,the crite- instructor can easilydevelop. ria are usuallyworkedout in advance.The criteriashouldbe exhaustiveenoughto ac- Whatto Count 304 themes that seem to be important (Abrahamson1983). The deductive approach,on the other hand, uses a coding schemedevelopedin advanceof the analysis. The researcherdevelops a hypothesis from a theoreticalframeworkand tests it usinga codingschemewhile performingthe analysis.A codingscheme-in this example one basedon the traditionalgenderdichotomy foundin many introductionto sociology textbooks-is providedto the students in advance. Althoughalmostanythingcan be counted when performinga contentanalysis,seven major elements are usually emphasized. These elements include words, themes, items,concepts,and characters,paragraphs, semantics(Berg 2001). For this exercise, studentsshould easily be able to identify words,themes,andcharactersrelatedto the traditional gender dichotomy. Students shouldbe instructedto look for these elementsin the book'stext, as well as the use of color, the storyline,phrases,picturesand anythingelse relatedto gender. CodingFrame This exercise employs a coding frame to organizethe dataandto help studentsidentify findingswhile analyzingthe books. I have used the coding framepresentedhere with great success, and instructorsshould findit easy to reproduce(see Appendix). TEACHING SOCIOLOGY EXERCISEDELIVERY StepOne Startby dividingthe class into smallgroups of two or three students.I have used the exercisein largerclasses wherethe groups can be as largeas five students,althoughin largergroupsthe chanceof socialloafingis greater.Once the groupshave been established, allow themto select a book to analyze and handout the coding sheets. Each group should have one book, one coding sheet, and a copy of the traditionalgender roleslistedin Figure1. At this point, give the studentsexplicit aboutwhatthey are expectedto instructions do. Explainthatthey are going to readthe booksandlook at the pictureswith the specific goal of determiningto what extent genderstereotypesare present.The importanceof systematically linkingtheiranalyses to the datacannotbe overemphasized (Stalp and Grant2001). This is accomplishedby askingthe studentsin eachgroupto develop operationaldefinitionsof the genderstereotypestheywill code. I like to use a dialecticalapproachthat mixes inductiveand deductivetechniques. Studentsfirst take a cursorylook at each book to see whetheror not genderstereotypesarepresent.For example,if the group thinksthe book containsan exampleof a womanbeing passive, they begin to try to GenderStereotypes* Figure1.GenderThemesBasedon Traditional Traits Masculine Traits Feminine Dominant Submissive Independent Dependent Intelligent Unintelligent Emotional Receptive Intuitive Weak Timid Content Passive Cooperative Sensitive Sex object Attractivedue to physical appearance "*Foundin Macionis (2001). Rational Assertive Analytical Strong Brave Ambitious Active Competitive Insensitive Sexually aggressive Attractivedue to achievement CONTENTANALYSISAND GENDERSTEREOTYPES 305 identify other behaviors associated with they findandtheycan countandtallyexamdefinition. passivity.I instructthe studentsto writeout ples for eachoperational their operationaldefinitions so that they mayreferto themwhilecodingin steptwo. Step Three Whenthe studentsare finishedcodingtheir Two books, ask two or three groups to share Step Once everythinghas been handedout and their findings and observationswith the the instructionsgiven, the instructoracts as class. Ask each grouppresentingto explain a facilitator.Some groups will need more their operationaldefinitionsand how they thanothers, and in my ex- codedexamplesof genderstereotypes.Genencouragement with the exercise, studentsasking erally, students explain their operational perience for help will adoptan instructor'sinterpre- definitionsandthenpointout picturesfrom tationverbatimif they can. The instructor theirbookor readtext fromtheirparticular shouldmakeeveryeffortto avoidprojecting book thatthey feel exemplifiestheirdefinionto the groupif tions of gender stereotypes.While each his or her interpretations asked for help. One idea for limitingthe groupis presentingits findings,the instrucinstructor'sinfluencein the codingprocess tor writessummarieson the boardthatwill is to reservea book to whichhe or she can help studentsdraw conclusionsfrom the referwhenansweringquestionsandprovid- exerciseandfacilitatethe discussion. ing examples. The goal is to get the studentsto do the StepFour coding. Instructthem to be consistentand Studentswill take the exercise more seriencouragethem to analyze the data mi- ously if they know there will be some asnutely,pointingout, for instance,thatcer- sessmentof their work. To thatend, I ask tain colors are frequentlyassociatedwith studentsto writea short(1-2 pages)reflecgenderand that this fact shouldbe part of tion paperin whichthey discusswhatthey their observations. Likewise, students learnedfrom the exercise. Instructorswho shouldexaminethe text, and even certain wish to give studentsmore time to conduct words, for genderstereotypes.The nature, a latentanalysiscan do so duringthis step type, andnumberof characters,characters' by allowingthemto take the book home. I body size, behaviors,and even the title of performanothercontentanalysisof the rethe book shouldall be examinedby the stu- flectionpapersandthenpresentthatdatato dentsto uncovermanifestandlatentgender the class at a laterdate. The commentsand remarksreportedin the discussionsection stereotypes. All the membersof the groups should come fromthe studentreflectionpapers. participatein the codingprocess, and they shouldenterdataon the coding sheet only DISCUSSION whenthey are generallyin agreementabout whetheror not a stereotypeis present. In Over severalyears of conductingthe exerthis partof the exercise, studentsshouldbe cise, I have discoveredthat the discussion allowed to disagreeand discuss their dis- portionof the exercise tends to gravitate agreementsbecausethis helps themdevelop towardsome fairly predictableissues and a deeperunderstanding of the process(Stalp themes. Whilea varietyof issues emerge, and Grant2001). Additionally,encourage students repeatedlyinvoke three general them to jot down their thoughts on a separate sheet of paper to refer to later during the discussion and to help them write the reflection paper. Students can code in both a qualitative and quantitativemanner: they can write out explanationsof the stereotypes conclusions: 1) the book is only a book and we are reading too much into it-children are not affected by the ideologies in the books; 2) things have changed and more recent children's books no longer reflect attitudes about gender, especially for 306 TEACHING SOCIOLOGY women; and 3) the books simply reflect dren'sperspectivesaboutgender,as gender schema theory suggests. Moreover, it is reality. the claim that the Regarding analysis apparentthat these women had not previreadstoo muchinto the books, it is impor- ously given much thoughtto the gender tantto pointoutto studentsthatchildrenare rolesactuallyportrayedin the books. just beginningto acquireself and personal- In turn, this female student'sreflection her abilityto find genity at the very time they are readingthese handilydemonstrates books. In otherwords, they are beginning derscriptsandthemesin children'sbooks: to learn how to organize their behavior Therewasa partin thebookwherea female along the patriarchal,genderedcodes emdog askeda maledog if he likedher hat. beddedin suchbooks. It can also be pointed Everytimehe saidno, untilin theendhe fiout thatchildrenwill face similarmessages nallysaidyeswhenshehadonthemostfancy from the broader cultural milieu. Aside hat.Thelastpictureshowedthemgoingoff from the messagesthey contain,the books This was a symbolof powerof together. are themselvessocial artifactsthat do not looks.Showinghow the maledog wouldn't exist in a vacuum, but in relationshipto takeheruntilhe likedherhat,andthatthegirl otherartifactsand social relations.Gender him. doggota newhateachtimeto impress ideologiesapparentin the books are also embeddedin children'stoys, the mass me- This observationcertainly illustratesthe dia, and even clothing. It is thereforeim- connectionbetween gender scripts in the portantthat students learn to see these media and the continuingimportanceof booksas only one componentof patriarchal personal attractivenessfor women. Thus, gendercodes. If languagedoes shape and women in the classroombegin to underconditionour perceptionsof reality, then standthattheymayhaveinternalized certain parentswho desireequalityfor theirdaugh- behaviorsandattitudeswith respectto their tersor egalitarianism for theirsons oughtto appearancewhen they were very young. look moreclosely at whattheirchildrenare Conversely,the same is true of the men, reading.Studentswho expectto be parents, who begin to see thatthey have learnedto or perhapsalreadyare, can gaina greatdeal see women,partly,as sexualobjects. of insightfromthe exercise. Anothercommonthemethattendsto surI have kept studentsummariesof the ex- face duringthe discussionis the claim that ercise for several years and presenthere gender inequalityis a thing of the past. someof theirmoreinterestingobservations. Whileit is true thatsignificantsocial, eduIn relationto whetheror not genderideolo- cational,and occupationalgains have been gies and stereotypesare present in the madeby women,thereis still a long way to books, two female studentsmake the fol- go beforegenderequalityis reached.Gender stratificationremains apparentin the lowingcomments: family, in education,in the mass media,in I haveneverthought of theseideasas I have the laborforce, in housework,in the distrireadthesebooksto my children.I am quite butionof incomeand wealth, and even in offendedby the messagesthatare so craftily politics (Bernard1981; Bianchiand Spain hidden bytheauthors. 1996; Charles 1992; Davis 1993; Pear 1991;OllenI neverrealizedhow children'sbookscould 1987;FullerandSchoenberger and Moore 1992; Waldfogel1997). have such stereotypical views withinthem. burger However,nowthatI am awareof theseunder- Even when women are in the work force lyingviews, I will be moreobservant. they often encounter a glass ceiling which prevents their rising much beyond middleFrom these observations it seems clear that level management (Benokraitis and Feagin the exercise helps students understandthat 1995; Yamagata et al. 1997). Women still children's books can actually influence chil- face a considerable amount of violence in CONTENTANALYSISAND GENDERSTEREOTYPES 307 A thirdinterpretation oftenvoiced during discussionis that the books simply reflect reality.Witha little effort, studentscan be spurredinto thinkingof lots of womenand men they have knownor knowwho do not fall into the traditional definitions of "feminine" and "masculine." In other words, not all men are dominantand independent, nor are all women submissive, passive, and dependent,as suggested by genderstereotypes.If the booksdo not accuratelyreflect realityfor boys, they do a worsejob of reflectingrealityfor girls, who are nearly invisible in them. Moreover, researchsuggeststhatmost childrendo not developconsistentlyfeminineor masculine (Bem 1983;Bernard1981). personalities a and reads sits down studentscommentedon someone female Several Until actually bookand analyzeseverypictureand word, how accuratelythe booksreflectreality: you don'tsee the hiddenmessagesor probthatkidsare beingexlemswithinequality Notall boysarebad,notall girlsareprissy. posedto. It wasn'tjust in one or two of the notall fathers arehousewives, Notallmothers and books.Therewere cases of inequality aredoingallthework.Therewerejusta lotof ineverybook. cultural different messages inthebooks. wrongmessages the home (Gelles and Cornell 1990; Schwartz1987; Smolowe 1994; Strausand Gelles 1986) andunwantedsexualattention outsidethe home (Loy and Stewart1984; Paul 1991). As partof theirpreviouslearning in the course, studentsshouldbe well awarethat genderstratificationstill exists. Therefore, in considering their findings from this exercise, students should be pressedto thinkaboutthe ways certainchildren's books supportand help reproduce genderstratification. While consideringwhetheror not negative gender stereotypesfor women are a thingof the past, two malestudentscontributedthe followingcomments: Gender playsa largerolein thesebooks.For inthesebooksit is veryrarethatyou instance, will see the malebeingshorterthanthe fethe malein a male,or the femaleprotecting is almost female The situation. dangerous and the follower as the alwaysportrayed in leaderis morelikelythemale.Themothers whostay thesebooksareusuallyhousewives homecleaningandcookingall day.Whilethe andcomeshome fathergoesto a jobeveryday withthechildren,or relaxes androughhouses aftera hardday'swork.Someof thesethings mayhavebeentrueat thetime,butin today's societymostwomenworkeverydayto help earna living. Livingintheworldas a femaleI wouldliketo believethatnoneof thatwastrue,butfromall thatwe have thefactsandlearning everything inclassI believeotherwise. These commentsclearly draw attentionto the lack of accuracy,let alonediversity,in some children'sbooks. One of the advantages of the exercise is that studentsare clearlyable, with a little prodding,to realdo not accuize thatthesechildren's-books of either behavior the actual reflect rately instructors most I think All in all, gender. who decideto try the exercisewill be pleasantlysurprisedby the level of sophistication The observationsaddressthe pervasiveness studentsare able to achieveusing the stuof genderstereotypesin the books as well dent-friendly methodof contentanalysis. as the dissonancebetweenwomen'sstereotypeddomesticroles and the contemporary ASSIGNMENT TAKE-HOME realityof workingwomen.Bothmen admitted that they had, as a matter of fact, read the books when they were children. Thus, students are able to understand that when the books were actually published is a moot point if parents are still buying them for their children. One of the central issues this exercise raises is the question of whether or not the gender stereotypes embedded in children's books simply reflect innate differences between the sexes or whether they are, in fact, reproducing and reinforcing culturally-based 308 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY genderstereotypes.Althoughthis exercise cannot directly determine the extent to whichany particularstudent'sgenderidentitywas influencedby children'sbooks,it is an issue studentsshouldbe asked to consider. To that end, instructorsmay find it useful to assign studentsa take-homeproject in whichthey conductfurtheranalysis of genderin the media. These take-homeassignmentscan take a variety of forms, but I have found two strategiesto be particularlyeffective. The first strategy asks studentsto reexamine mediathey were familiarwith as children. In this case, studentsare directedto recall theirchildhoodandto identifytheirfavorite children's books, cartoons, storybooks, textbooks,and even games. They are then instructedto locatesamplesof thatparticular mediaand conducta latentanalysisfor genderstereotypesin a mannersimilarto the class exercise.The secondstrategyasks studentsto conducta broaderlatentanalysis usingcurrentmedia.Thisanalysiscan focus on advertisements,commercials, magazines, and television programs such as situationcomedies, or movies. For example, certain, if not all, Disney movies (includingTheLion King, The Little Mermaid, and Aladdin)lend themselvesquite well to a latent analysisof genderstereotypes. Ask studentsto writea threeto five page essaybasedon theirchoiceof strategiesand one (or some combinationof) suggested topics. In orderto complementthe in-class exercise, their essays should address the followingissues: "* identifiablegenderstereotypes * similarityof sample to those gender stereotypesfoundin the class exercise "* what role the mediaplays in transmitting genderstereotypesto futuregen* * erations how accurately students believe the gender stereotypes describe themselves or other women and men they know to what extent students have incorporated gender stereotypes as part of their * genderidentity to what extent students'gender roleperformancesapproximatethe gender stereotypesandin whatsocialsettings The take-home assignment, therefore, shouldnot only be fun and interesting,but also help studentsaddressand think about the extent to which the media perpetuates genderstereotypes. CONCLUSION Gender is perhaps the basic dimension throughwhich individualsperceivethe social world and their place in it. Gender shapes social organizationand influences how we interactwith each other and even how we evaluateourselves. Additionally, gender shapes our feelings, thoughts,and behaviors from birth to death. Children learnearlyon thatsocietyhas differentexpectationsand standardsfor girls andboys. However, before childrencan learn what the standardsare and therebyapply gendered standardsto themselves,they must learnthe gendercode. This code is clearly embeddedin the children'sbooks used in the exercise.Sincechildrenbeginto understandgenderand apply genderstereotypes to themselvesat an early age, we can reasonablyask what such books are teaching childrenaboutgender. This female student'sreflection,I think, the exercise: aptlysummarizes Toseehowthesebooksweremeantto encourlittlegirls,wasjust agelittleboysanddegrade shocking.Duringthe class discussion,it seemedthatmostof thebookshadalmostall male characters doingeverythingimportant if any,werealwaysin andfemalecharacters, werestrong roles.Malecharacters secondary Whilefemale andshowedlotsof imagination. characterswereweakerandusuallymoresubdued, with theirpinkbows and clothing.If a motherfigure appearedin a book she was always cleaning or cooking. Father figures workedhardand were more of the authority figure. All the charactersseemedwhite and middleto upperclass. All the troublemakers CONTENTANALYSISAND GENDERSTEREOTYPES or everythingthatwas evil or badwas colored in black, while everythinggood and happy was coloredin primarycolors.Thinkingabout all thesemessagesremindedme of how whenI was youngermy fatheronce saidto me, "You hammerlike a girl,"to whichI replied,"What thehelldoesthatmean?"He hadno answer. From these remarks it seems clear that the exercise is one that does indeed help students recognize gender stereotypes in popular children's books. Indeed, the exercise is easily adaptedto other media and other ideologies and stereotypes. I conclude with a comment from one of the male students, who had a somewhat broader view of the exercise: 309 I realizedthat childrenare introducedto racism, social class, and sexualroles at a very youngage andtheydon'tevenknowit. I think the reasonwe did this exercisewas to prove the point that we, as children,are unableto avoidthesebiaseswe growup with. Theyare everywhere,even in children'sbooks. I often hear colleagues despair over whether or not their students are "getting the message" when the message is related to gender or some other form of inequality. Content analysis is, in my estimation, a useful tool which can be added to one's inventory of teaching strategies. APPENDIX. CodingFrame:FemaleGenderStereotypes Submissive Dependent Unintelligent Emotional Receptive Intuitive Weak Timid Content Passive Cooperative Sensitive Sex Object Attractive CodingFrame:MaleGenderStereotypes Dominant Independent Intelligent Rational Assertive Analytical Strong Brave Ambitious Active Competitive Insensitive SexuallyAggressive Achievement 310 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY REFERENCES Abrahamson,Mark. 1983. Social Research Methods. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Bem, SandraLipsitz. 1981. "GenderSchema Theory:A CognitiveAccountof Sex Typing." Review88:354-64. Psychological . 1983. "Gender Schema Theory and its Implicationsfor Child Development:Raising Gender-SchematicChildren in a GenderSchematicSociety."Signs:Journalof Women in CultureandSociety8:598-616. _ . 1984. "Androgyny"and Gender-Schema Theory:A Conceptualand EmpiricalIntegration. Nebraska Symposiumon Motivation: Psychologyand Gender32:179-226. _ . 1993. The Lenses of Gender: Transform- ing the Debate on Sexual Inequality.New Haven,CT:YaleUniversityPress. Benokraitis,Nijole andJoe Feagin. 1995. Modem Sexism:Blatant, Subtle, and OvertDiscrimination.2d ed. EnglewoodCliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall. Berg, Bruce L. 2001. QualitativeResearch Methodsfor the Social Sciences.4th ed. Boston, MA:AllynandBacon. Berger,PeterL. 1963.Invitationto Sociology:A HumanisticPerspective.New York: Doubleday. Bernard,Jessie. 1981. TheFemale World.New York:FreePress. Bianchi,SuzanneM. and DaphneSpain. 1996. "Women,Work, and Family in America." PopulationBulletin51(3):1-47. Variation Charles,Maria.1992. "Cross-National in OccupationalSegregation."AmericanSociologicalReview57(4):483-502. Clark,Roger,RachelLennon,andLeannaMorris. 1993. "Of Caldecottsand Kings: GenderedImagesin RecentChildren'sBooks by Black and Non-BlackIllustrators."Gender andSociety7(2):227-45. Crabb, Peter B. and Dawn Bielawski. 1994. "The Social Representation of MaterialCulture and Genderin Children'sBooks." Sex Roles,30:69-79. Davis, DonaldM. 1993. Cited in "T.V. Is a Blonde,BlondeWorld."Pp. 34-41 in American Demographics,Special Issue: Women ChangePlaces, vol. 15, no. 5. Ithaca,NY. Eagly, Alice H. andWendyWood. 1999. "The Originsof Sex Differencesin HumanBehavior: Evolved Dispositions Verses Social Roles."AmericanPsychologist54:408-23. Fuller, Rex and RichardSchoenberger.1991. "The Gender Salary Gap: Do Academic Achievements,InternExperience,andCollege Major Make a Difference?"Social Science 72(4):715-26. Quarterly Gelles, RichardJ. and ClairePedrickCornell. 1990. IntimateViolencein Families. 2d ed. NewburyPark,CA: Sage. Heck, M.C. 1980. "TheIdeologicalDimensions of Media Messages."Pp. 66-72 in Culture, Media,Language:Working Papersin Cultural Studies, 1972-1979, edited by Stuart Hall. New York:Hutchinson andCo., Ltd. Holsti, Ole. R. 1968. "ContentAnalysis."Pp. 596-692 in TheHandbookof Social Psychology, vol. II, editedby GardnerLindzeyand Elliott Aaronson. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley. . 1969. Content Analysis for the Social Sciencesand Humanities.Reading,MA: Addison-Wesley. Loy, PamelaHewittand Lea P. Stewart.1984. "TheExtentandEffectsof SexualHarassment of Working Women." Sociological Focus 17(1):31-43 Macionis, John, J. 2001. Sociology. 8th ed. UpperSaddleRiver,NJ:PrenticeHall. Mead, GeorgeHerbert.1934. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago,IL: Universityof Chicago Press. Mills, C. Wright.1956. TheSociologicalImagination.New York:OxfordUniversityPress. Ollenburger,Jane C. and Helen A. Moore. 1992.A Sociologyof Women:TheIntersection of Patriarchy,Capitalismand Colonization. EnglewoodCliffs, NJ:PrenticeHall. Paul, Ellen Frankel.1991. "BaredButtocksand FederalCases."Society28(4):4-7. Pear, Robert. 1987. "WomenReduce Lag in Earnings,But Disparitieswith Men Remain." New YorkTimes,September 4, pp. 1,7. Sapir,Edward.1929. "TheStatusof Linguistics as a Science."Language5:207-14. . 1949. Selected Writingsof Edward Sapir in Language,Culture,and Personality.David G. Mandelbaum, ed. Berkeley,CA: University of CaliforniaPress. Schwartz,MartinD. 1987. "Genderand Injury in Spousal Assault." Sociological Focus 20(1):61-75. Selltiz, Clair, Marie Jahoda,MortonDeutsch, andStuartW. Cook. 1967. ResearchMethods in Social Relations.2d ed. New York: Holt, RienhartandWinston. Smolowe, Jill. 1994. "When Violence Hits Home." Time,Vol. 144, No. 1, July 4, pp. 18-25. CONTENTANALYSISAND GENDERSTEREOTYPES Stalp, MarybethC. and Linda Grant. 2001. "TeachingQualitativeCodingin Undergraduate FieldMethodsClasses:An ExerciseBased on PersonalAds." TeachingSociology29:20918. Straus,MurrayA. and RichardJ. Gelles. 1986. "SocialChangeand Changein Family Violence from 1975 to 1985 as Revealedby two NationalSurveys."Journalof Marriageand Family48 (4):465-79. Strauss,Anselm L. 1987. QualitativeAnalysis for Social Scientists.NY: CambridgeUniversity Press. Taylor, Frank0. 1998. "The ContinuingSignificanceof StructuralMarxismfor Feminist SocialTheory."CurrentPerspectivesin Social Theory18:101-29. Waldfogel,Jane. 1997. "TheEffectof Children on Women'sWages."AmericanSociological Review62 (2): 209-17. Walzer,Suzan.2001. "DevelopingSociologists ThroughQualitativeStudy of College Life." TeachingSociology29:88-94. Weitzman,LenoreJ., DeborahEifler, Elizabeth Hokada,andCatherineRoss. 1972. "SexRole 311 Socializationin PictureBooks for Preschool Children."AmericanJournalof Sociology77 (May):1125-50. Whorf, BenjaminLee. 1956. "The Relationof HabitualThoughtandBehaviorto Language." Pp. 134-59in Language,ThoughtandReality, editedby John B. Carroll.Cambridge,MA: TheTechnologyPressof MIT/NewYork. Williams,J. Allen,JoEttaA. Vernon,MarthaC. Williams, and KarenMalecha. 1987. "SexRole Socializationin PictureBooks: An Update." Social Science Quarterly 68 148-56. (March): Yamagata,Hisashi,KuangS. Yeh, ShelbyStewaman,and HirokoDodge. 1997. "Sex Segregationand Glass Ceilings:A Comparative Static Model of Women'sCareerOpportuniover a Quarter ties in the FederalGovernment American Journal Century." of Sociology 103(3):566-632. in sociology FrankTaylorreceivedhis doctorate He is curof Nebraska-Lincoln. fromtheUniversity at Edinrentlythechairof thesociologydepartment andthe directorof of Pennsylvania boroUniversity sociology. applied