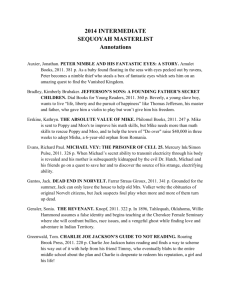

Lisa Harris - RMIT Research Repository

advertisement